Leigh Byford was in transit in Singapore when his back went out. He would spend more than 14 hours in excruciating agony, downing scores of pain killers to no effect.

It was 2011 when Mr Byford, his wife and their two young children, boarded a flight from South Australia bound for Germany.

They were on a family holiday for a friend’s wedding, with plans to visit their old haunts in London. Yet, just hours into their trip, the then 34-year-old’s back seized up – it was the chronic pain he had been forced to live with since he was in his early 20s.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2F200f91e1-4fa8-4066-b2b3-5e9b0c273e0a)

“I got a locum doctor (in Singapore) to get me some pain killers and then I tried to ‘get through’ to Heathrow,” Mr Byford, a nurse, told 9News.

“So, I spent the entire flight in nine out of 10 pain. I wasn’t screaming, but I was close.”

He recalled sitting in the footwell of his economy seat, gobbling a cocktail of pills and alcohol in search of relief. None came.

‘It was lucky I didn’t die… I think I took about 18 tramadol, about 10 panadeine forte, whisky, anything’

“I sat with my knees on the ground with my head just on a pillow or something and I took, just to get through the flight,” he said, pausing to think.

“It was lucky I didn’t die… I think it’s a 10 or 12-hour flight… I think I took about 18 tramadol, about 10 Panadeine Forte, whisky, anything,” he said.

“I was just in intractable pain.”

When the family arrived in Germany, Mr Byford said he was bedridden for the first two weeks of their trip. His pain was so severe he would miss the wedding.

“It was awful, my wife had to carry all the bags, we had two young kids with us. It was a nightmare,” he said.

Mr Byford was 24, and in his second year at university studying nursing, when he developed chronic lower back pain. He felt his back go after a day at the skate park, and it never recovered.

“At the time it was just excruciating pain in your lower back, so, it’s probably more akin to having like a rotten tooth or something,” he said.

“So, whenever you move you get this incredibly sharp pain and then you have this really nasty dull ache in your lower back which is right in the base of my spine.” After countless GP visits, and no firm diagnosis, he tried a variety of treatments to manage the constant pain.

“Initially, I guess you try rest. I would have tried pain killers, anti-inflammatories,” he said.

“People just assumed it was a disc issue and there’s no good measure where you can look at the amount of damage that’s happened to someone’s back and be able to accurately predict how much pain they are going to be in. So, looking at somebody’s CT and X-ray is not massively helpful.”

‘One of the things I found difficult at that age, and right the way through… it was more about masculinity as well’

As a result of the pain, Mr Byford said he became very protective of his back, as he believed he had a mechanical weakness.

“I was very concerned about it getting worse. So, I used to be overly protective of my spine,” he said.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2F8b435686-a276-4f5b-a0c0-da4bcca544dd)

“They put me onto a Pilates programs, strengthening programs. I tried physiotherapy, osteopathy… I did something called cold laser therapy, I had acupuncture on top of just general analgesics.”

He said he found the first four years living with chronic pain the most difficult, psychologically, in terms of depression and a feeling of loss of hope for his future.

“One of the things I found difficult at that age, and right the way through, until I started getting better in my mid-30s… it was more about masculinity as well,” he said.

“Like if you go to a Bunnings and go to lift something and I couldn’t because I’d be too scared I’d hurt myself. So, I’d always end up getting my wife to carry things.

“I remember one time just being in the car, I was in heaps of pain, and all I could do was just sit in the car. I just came along for the drive… and some guy gave me this hiding while my wife was at the back of the car loading the car up.

Mr Byford said because chronic back pain doesn’t immediately reveal itself outwardly, many people “can’t see anything wrong with a person”.

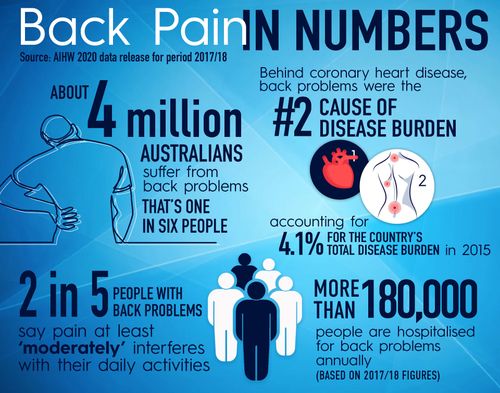

Research from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, released in August last year, found about 4 million people, or one-in-six Australians suffer back problems.

In 2017-18, there were more than 180,000 hospitalisations for back problems.

In 2015, back pain was the second leading cause of “disease burden”. It accounted for 4.1 per cent of Australia’s total disease burden.

“Back pain- low back pain in particular is the most common chronic pain and the most burdensome,” Professor Lorimer Moseley, chair of Physiotherapy at the University of South Australia, told 9News.

‘Most people associate back pain with a vulnerable back and actually one of the most extraordinary body parts is our back’

“It causes the biggest impact across society of the costs of treating it. Back pain is complex. Back pain is influenced by a range of things.”

Professor Moseley, who is also the CEO of Pain Revolution, said the most common aspect of back pain that can be treated effectively is movement and loading of the back – something that is counterintuitive to our understanding of back pain.

“Most people associate back pain with a vulnerable back and actually one of the most extraordinary body parts is our back. It is so strong,” he said.

“And it is fit for purpose but we’ve tended to move towards this society where we think backs are weak so if we have back pain we have a weak back.

People try to strengthen the back, even though they’re worried all the time, and people are afraid of bending over. A common theme in people with back pain is the expectation their back will break in some way under loads they’re already doing without realising.”

Professor Moseley said there are two common misunderstandings about back pain “that drive me nuts”.

The first, he said, is the very common label of a slipped disc.

“The disc is the part of the body that joins one vertebra to the next vertebra, and it’s made of ligament and cartilage and it’s so tightly integrated with your vertebra that there’s no way every anybody could have a disc slip,” he said.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2F34c6cbce-bda3-4f01-8e54-c5a6aa26934d)

“The phrase arose from looking at scans and seeing the disc with a different shape. And it looks, from side on like something might have slipped.”

“But what’s actually happened is those ligaments have stretched over time. And that’s a normal part of ageing. You cannot actually slip a disc.”

He said, broadly speaking, the most common misunderstanding from anyone who’s had a scan of their back is the observations of the scan represent damage.

“Usually they do not,” he said.

“They represent a change in the structure in the back in order to be better at withstanding the loads of your life.

“For me, my vertebrae have changed shape to be stronger because I’ve done a lot of manual and sport. If you took a scan of my back they would be reported as abnormalities.”

It was a chance conversation during work that Mr Byford finally learned of his condition.

He had just returned home from the family holiday in Germany, and in a bid to seek answers, soaked up any research studies he could find about chronic lower back pain.

After speaking with his treating doctors, a conversation with one of the nephrologists he worked with proved life changing.

Mr Byford was referred to a rheumatologist, who diagnosed him with ankylosing spondylitis – an inflammatory disease which can cause some of the small spinal bones to fuse.

“The best way to treat the condition I have is exercise, aerobic exercise but not impact. So, things like riding a bike, and swimming and just maintaining your fitness,” he said.

“I take Panadol osteo and Nsaids, when I have to. Ultimately what would be preferential is these days there’s these particular medications known as biologic medications…but essentially the PBS (Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme) criteria is really, really hard so I can’t afford the medication.”

Mr Byford said it would cost him $400 a week for the medication, but only $8 a week on the PBS.

“The thing that surprises me is that there are different ways of measuring the disease,” he said.

“The way they (PBS) measure it is they scale the amount of damage that’s happened to the spine and pelvis. I think with a plain x-ray they can judge the amount of bone change.

“So, they scale it one to four and so four is someone wheelchair bound, can’t move at all… so with ankylosing spondylitis, apart from the inflammation, the other tissues ossify and become bone… it basically fuses it all up.” He said he’s classed as a stage two, and would need to be a stage three to qualify for the government benefit.

“If you were stage three you’d be hard pushed to be working. So, I find it slightly bizarre that they wouldn’t supply the medication to try and reduce the progress of keeping someone working essentially,” he said.

These days, Mr Byford remains in chronic pain, but continues to focusing on managing it as best he can.

“I always have some level of pain. Early on it was much worse. I was probably sitting at about seven out of 10 pain all the time. Maybe it would get down to five, and now for what it’s worth, it’s about a two,” he said.

“I’m still very careful about how I lift things but since I got the diagnosis that it’s an inflammatory back pain rather than a mechanical source it sort of freed me up psychologically to approach it slightly differently.

“So now I try and do as much as I can to be honest.”

This content first appear on 9news