Introduction

As COVID-19 vaccine distribution continues and expands to larger segments of the population, early KFF analysis of state-reported data raise concerns about disparities in vaccinations for Black and Hispanic people. Ensuring equitable access to the vaccines will be important to mitigate the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic for underserved populations, prevent widening disparities going forward, and achieve broad population immunity. The Biden administration’s national COVID-19 response strategy outlines equity as a key priority, including as part of vaccine distribution efforts. Some states have also emphasized equity as a priority in their vaccine distribution plans and, in some cases, have taken responsive action to address disparities in vaccinations revealed by early data.

This brief reviews information available through state websites and publicly available vaccine distribution plans as of February 2021 to provide greater insight into how states are addressing equity through vaccine allocation and distribution strategies, outreach and communications efforts, and data collection and reporting. The review seeks to provide a snapshot and examples of state efforts in these areas. However, this review does not provide a fully exhaustive summary of all state actions, and given the rapidly evolving nature of state vaccination efforts, it may not reflect the latest developments in state approaches. Beyond the state-level strategies highlighted in this review, efforts to advance equitable access to the vaccines are also underway at the city and county level, among health systems and providers, and in the private sector. Moreover, the federal government is implementing a range of approaches to expand vaccine access and uptake — including direct distribution through community health centers — with a particular focus on reaching underserved areas and communities hardest hit by the pandemic.

Vaccine Allocation and Distribution

Where and how people can sign-up for and access vaccines has direct implications for who will receive them. People living in underserved and disproportionately affected areas may face increased challenges accessing vaccines due to more limited resources available to navigate online sign-up systems, lack of transportation, and other access challenges. States are employing a range of strategies to increase the availability and accessibility of vaccines for disproportionately affected areas and people.

Some states are allocating additional vaccine doses to enhance vaccine supplies in underserved and disproportionately affected areas. About half the states indicated in their vaccine distribution plans that they planned to use the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) or similar indices to inform their vaccine allocation strategies. States varied in the level of detail they provided in their plans on how they would use these resources to inform their allocation approach, although some states have provided more specific implementation details. For example, in December, Governor Baker of Massachusetts pledged to allocate 20% additional vaccines to communities with high social vulnerability to help address the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on people of color. New Hampshire has indicated that it will reserve 10% of its vaccine supply for allocation to communities that have been hard hit by the pandemic. Connecticut reports providing an additional roughly 10% of the state’s allocation to areas that have high vulnerability based on the SVI. North Carolina also reports allocating additional doses to counties with larger older populations and historically marginalized populations. They indicate that vaccines will be invested into projects and events that promote increased access and partnerships in the community, with a particular focus on achieving equitable access to the vaccine. California will begin reserving 40% of vaccines for residents in the most disadvantaged areas of the state.

Some states are prioritizing vaccine appointments or eligibility for certain groups or areas. In response to early data showing gaps in vaccinations in certain wards of the city, Washington DC changed its vaccine appointment system to prioritize people living in these low-income, underserved areas. Residents in these wards are given the opportunity to register for vaccine appointments 24 hours before they become available to people living in other areas of the city. California provided codes that would provide access to vaccine appointments to community organizations that were intended to be distributed to people living in largely Black and Hispanic communities, although media reports pointed to problems with the initial rollout of this approach. Rhode Island has taken a different approach of prioritizing eligibility for broader groups of residents in certain geographic areas that have an increased risk for COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths, including Central Falls and certain other areas of the state. Montana and Utah include people of color in their initial vaccine priority groups. With Montana vaccinating American Indians and people of color who may be at elevated risk for COVID-19 complications in Phase 1b, and Utah including people living in Tribal reservation communities and racial/ethnic groups at increased risk in Phase 1c.

Nineteen states have established call centers or provided text options to facilitate access to vaccine appointments for people who may not be able to navigate online sign-up systems. For example, Mississippi and Alabama have set up vaccine appointment scheduling hotlines for residents who cannot or do not want to use the web-based booking programs. In Maryland, the Departments of Health and Aging collaborated to create a telephone-based support line and appointment system designed to assist those without internet access. Connecticut is working with the United Way to provide a call center to schedule appointments that is available 12 hours a day and 7 days a week. However, many states have also encountered initial challenges with this approach, due to overwhelming demand. For example, New Jersey opened up a phone line to schedule vaccine appointments, but it was quickly stretched beyond its initial capacity. Some states are using text-based approaches to provide notifications of when appointments become available. Oklahoma is piloting a text-based notification system that sends second dose appointment updates to individuals who have registered for the vaccine through their scheduling portal.

Some states are deliberately locating vaccine clinics in underserved or disproportionately affected areas. For example, Tennessee is partnering with pharmacies and community health centers to add more than 100 vaccination sites, with a particular focus on rural and underserved areas. Colorado has outlined several strategies to increase the accessibility of vaccines, including partnering with counties to host community clinics, establishing community partnerships to reach communities of color, and coordinating with transportation providers to assist people without vehicles in getting to appointments. The state has also established a goal of having vaccines available through a community-based clinic in “50% of the top 50 census tracts with a high-density of low-income and minority communities.” Alaska is using an Area Deprivation Index to identify areas to provide targeted efforts to ensure equitable access to the vaccine through partnerships with Federally Qualified Health Centers and other community and locally-led organizations. While placing vaccine clinics in underserved or disproportionately affected areas can make vaccines more accessible to people living in areas, location alone will not necessarily ensure access if people face barriers completing sign up processes, and appointments are taken by people living in other areas. As such, prioritizing or reserving appointments for people living in those areas is also important.

Outreach and Communications Strategies

In addition to ensuring individuals can access the vaccine, making sure people receive clear information that explains how and when they can obtain the vaccine and addresses any concerns or questions they have about the vaccine also is important. Moreover, it is key for this information to be provided in culturally and linguistically appropriate ways through trusted messengers.

Some states are collaborating with and supporting community-based organizations and health centers to conduct outreach, communication, and education. For example, Massachusetts launched a targeted outreach initiative through which the Department of Health will invest resources directly into the 20 cities and towns most impacted by COVID-19 to increase awareness of vaccine safety and efficacy by working with local leaders and community- and faith-based groups. The state has also invested $1 million in the Massachusetts league of community health centers to provide grants to health centers to assist in engaging patients and community members in vaccination discussions and increase vaccination rates in the states’ hardest hit communities. The state of Washington has Community Outreach Services Contracts with several community-rooted organizations and groups to assist with COVID-19 vaccine outreach and makes investments in community/ethnic media outlets and community based organizations for community-driven messaging efforts. Colorado announced it is working to schedule more than 175 vaccine equity clinics across the state in partnership with community based organizations, local public health agencies, and Tribes, with community organizations playing a key role in providing outreach to their community members and registering people for appointments.

Many states are launching their own vaccination communications campaigns, often with a focus on reaching people of color and other groups who may face heightened barriers to vaccination. As part of its GoVAX outreach campaign, Maryland launched a mobile public health education unit—or sound truck—to provide information about COVID-19 prevention and vaccination availability in Spanish and English in selected neighborhoods that have been hardest hit by the virus. Volunteers will also distribute informational flyers and face masks at designated stops. In Ohio, health officials are hosting virtual town halls that will be replayed weekly on television to tackle COVID-19 vaccine myths. The town halls are focused on addressing questions and concerns of Black, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander, and rural residents. In addition to these outreach efforts, all states provide information through public-facing websites to address questions and concerns about the vaccine. For example, many prominently feature frequently asked questions (FAQ) sections that address common questions.

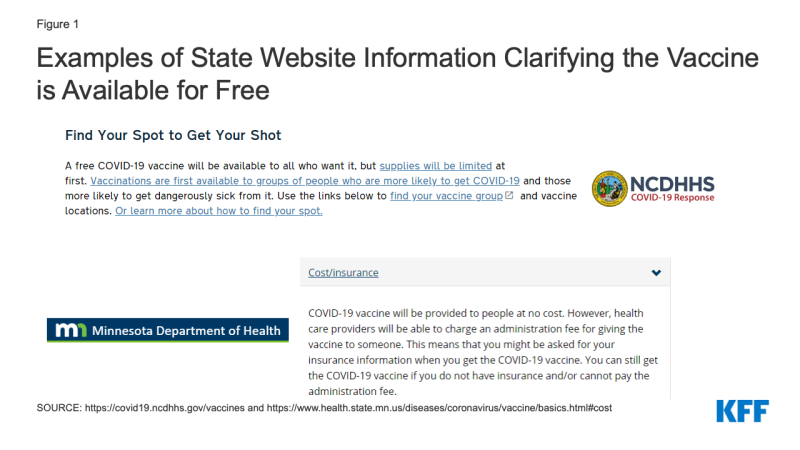

Most state websites include information clarifying that the vaccine is available for free, although the information is not always highlighted prominently. Some states highlight this information up front. For example, North Carolina clarifies that the vaccine is available for free to all who want it on its landing page for vaccine information (Figure 1). Similarly, Minnesota includes this information in the FAQs listed on its “vaccine basics” page. Clarifying that people can receive the vaccine at no cost regardless of insurance status is important for facilitating equity, as recent survey data show that Black and Hispanic adults have heightened concerns about potentially having to pay out-of-pocket costs. Possibly, even more important is whether vaccine providers clarify that the vaccine is available at no cost and ensure people are able to sign up for appointments without providing insurance information.

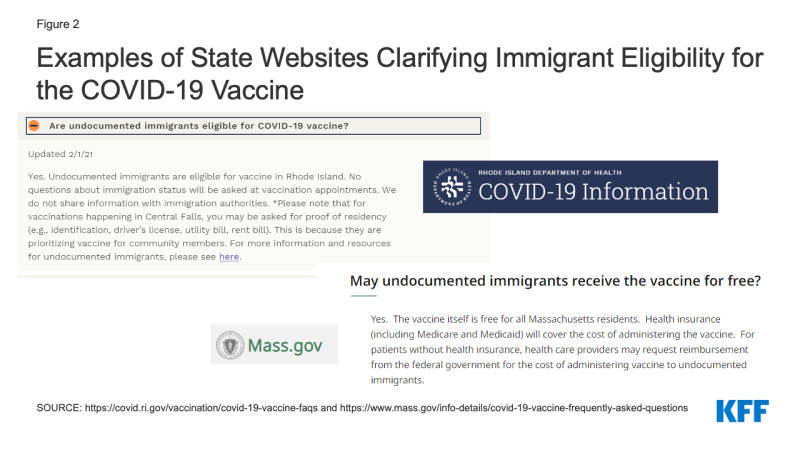

Fewer state websites clarify that individuals are eligible for that vaccination regardless of immigration status and/or that obtaining the vaccine will not negatively affect immigration status. Clarifying this information can help address fears and confusion that could present barriers to vaccination among immigrants. For example, Rhode Island clarifies that undocumented immigrants are eligible for vaccination and that information will not be shared with immigration authorities (Figure 2). In Massachusetts, they emphasize that the vaccine is free for all Massachusetts residents, and that health care providers may request reimbursement from the federal government to cover the administrative costs of providing vaccines to undocumented immigrants.

All websites provide options to access information in different languages, but they vary in how they provide this access. Some states solely utilize google translate or similar translation software; others provide translated materials through downloadable resources, in some cases linking to translated materials provided by CDC. However, recent reporting finds that many vaccine registration and information websites at the federal, state, and local levels violate disability rights laws, hindering the ability of blind people to sign up.

Data Collection and Reporting

Collecting and analyzing COVID-19 vaccination data by race/ ethnicity is integral to gaining insight into who is and is not receiving vaccines and can be used to direct resources and efforts to address disparities as they are identified.

As of March 1, 2021, 41 states are publicly reporting COVID-19 vaccination data by race and/or ethnicity. While most states are reporting data, the quality, completeness, and timeliness of the data vary widely across states, which affects its usefulness. For example, as of March 1, 2021, in Minnesota and Washington D.C., race/ethnicity information was missing for over 40% of vaccinations, while North Carolina reported less than 1% as missing race/ethnicity information. States also vary in the extent to which they disaggregate data to allow an understanding of the experiences of specific groups. For example, Florida groups people who report their race as Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or other into a single “Other race category.” In contrast, other states, like Maine, disaggregate data separately for racial and ethnic groups. Very few states report vaccination data by race/ethnicity and other demographic factors like age or gender. However, South Carolina and Washington provide data in these more detailed ways, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of who is being vaccinated that can inform efforts to address gaps.

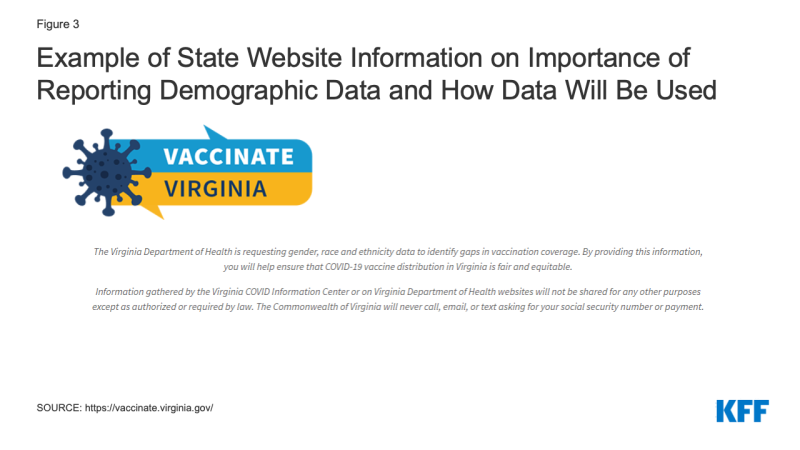

Several states have taken actions designed to increase the completeness of race/ethnicity data. For example, North Carolina and Texas are requiring vaccine providers to collect race/ ethnicity data. Texas is updating its immunization registry system so that race and ethnicity must be entered to complete the data entry process. Michigan added a hand-entry field into their registry system to collect race and ethnicity data since the system had not previously collected this information. In addition, Virginia added language to its website to encourage individuals to report demographic data and clarifying how the data will be used (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Example of State Website Information on Importance of Reporting Demographic Data and How Data Will Be Used

Conclusion

In sum, early data pointing to racial disparities in COVID-19 vaccinations underscore the importance of intentional efforts focused on ensuring equity as the vaccine rollout continues. As highlighted in this brief, a number of states included a focus on equity in their vaccine distribution plans and are taking responsive action to try to address emerging disparities through vaccine allocation and distribution approaches, outreach and communications strategies, and data collection and reporting. Continued monitoring of data to understand who is and is not receiving the vaccine will be important for gauging the effectiveness of these approaches; and will help guide ongoing efforts to prevent and reduce disparities as distribution continues.

As noted, beyond the state-level strategies highlighted in this review, efforts to advance equitable access to the vaccines are also underway at the local level, among health systems and providers, and in the private sector. Moreover, at the federal level, the Biden administration has outlined equity as a key goal of its national COVID-19 response strategy, including as a part of vaccine distribution efforts. To that end, it has established a COVID-19 Health Equity task force; indicated plans to work with states to incorporate equity into their vaccine distribution processes; is taking steps to expand vaccine availability in underserved areas through federally-supported vaccination centers and allocations of vaccine doses directly to community health centers and retail pharmacies; is launching and vaccination communication plan; and is focused on expanding data collection and reporting. The American Rescue Plan Act includes additional funding that will further enhance these approaches.