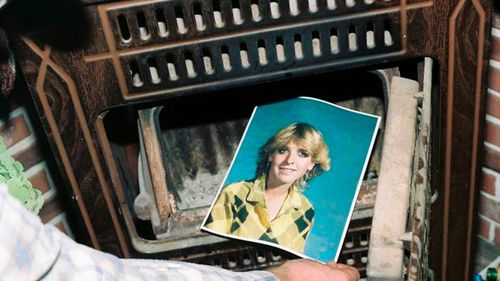

Pamela Pitts’ body was found burned beyond recognition in a pile of trash in 1988.

Tips flooded in blaming a Satanic cult, a drug dealer, an ex-lover, an overdose at an Arizona party spot.

It would take more than 30 years, some prison calls and an eyebrow-raising plea deal before a convicted murderer would confess.

But in a shocking twist, a court recently agreed the 19-year-old’s killer wouldn’t spend any more time behind bars.

Over the years, investigators couldn’t pin down the evidence they needed to arrest anyone in the slaying that stoked fear about a killer on the loose around Prescott, a tourist town about 160 kilometres north of Phoenix.

The tips didn’t add up. And then the case went cold.

Yet, suspicion followed Pitts’ roommate Shelly Harmon for the 20 years she spent in prison for fatally shooting her ex-boyfriend, Raymond F Clerx. As her sentence was ending, police started monitoring Harmon’s phone calls.

One call gave prosecutors what they said they needed. In it, Harmon’s father said she never told him what happened.

“I had a moment. I had a huge moment,” Harmon replied.

Dennis McGrane of the Yavapai County Attorney’s Office saw it as an admission of guilt.

“Like a sudden quarrel with the roommate,” he said.

“She wasn’t planning it, but she did do it.”

Harmon’s attorney, Dwane Cates, said the statement could have referred to Clerx’s death.

Clerx had wanted to end the relationship and was going to take their dogs. In a burst of anger, Harmon shot him as he lay on the roof of a car watching planes overhead. She later dropped his body in a mineshaft.

Harmon confessed. But with Pitts’ death, her story changed over the years: She said Clerx was her alibi. She claimed another roommate strangled Pitts.

Prosecutors tried to draw similarities between the two cases to back up a theory that when Harmon felt threatened or abandoned, she killed. Cates called that a stretch.

Prosecutors knew Harmon was furious with Pitts over money, for wanting to move out and for sharing news of Harmon’s pregnancy, according to court documents obtained by The Associated Press.

Pitts went missing on September 16, 1988, the day that Harmon drove around Prescott looking for her and saying she’d kill her if she found her, the documents say.

Harmon also said she knew how to conceal a killing: by burning a body or dumping it down a mineshaft — a statement a judge said could be included at a trial that was supposed to start last week.

But prosecutors were dealt a blow when the court ruled no evidence of Clerx’s death could be introduced.

Plus, the autopsy was inconclusive because of the extent of Pitts’ burns. The court said no one could suggest it was a homicide or probable homicide. Pitts’ body was identified through dental records.

Prosecutors acknowledged that they faced a trial without the evidence or witness recollections they had hoped for. That’s when they considered a plea deal.

“It weighed heavily on us, guaranteeing an outcome versus taking a chance at trial,” McGrane said.

Harmon’s attorney maintained the evidence was stronger against someone else.

But Yavapai County sheriff’s Lieutenant Victor Dartt said he followed leads until they no longer checked out.

“Shelly was the only one that I could keep corroborating,” he said.

Harmon, whose maiden name is Norgard, was charged with first-degree murder in 2017.

She was living outside Carson City, Nevada, after being released from prison for Clerx’s death. She got married, managed rental properties, and did bookkeeping and tax work.

Harmon had not registered as a felon as required in Nevada, so she was picked up and told of the murder charge later, Dartt said.

In March, she agreed to plead guilty to second-degree murder and detail how she killed Pitts.

Harmon recounted that she was upset Pitts was late on rent and had overdrawn a joint bank account. So, she went looking for her, the two fought and Harmon said, “I just lost it.”

She said she hit Pitts repeatedly against the ground until she was no longer moving. As voices drew near, Harmon said, she “freaked out”.

“I was thinking, ‘Oh, my God, she’s dead, she’s dead, and I killed her,’” Harmon said.

Pitts’ family found the account unbelievable, like half a story.

“It was just to get out of jail,” said Pitts’ brother, Paul Pitts Jr. “She got a golden ticket, and she got away with murder.”

Harmon was sentenced to 20 years but received credit for the time she served for Clerx’s death and the years she spent in jail awaiting trial in Pitts’ slaying.

Still, the Pitts family celebrated — it wasn’t justice, but it was an ending to the decades long case.

They remembered the 19-year-old who exuded 1980s rock style and whose room always smelled like Aqua Net hair spray.

She loved animals, took care of the elderly, was kind and bubbly but also had a tough, know-it-all side, her family said.

Pitts’ mother, Carol, said Harmon will have to live with killing her daughter for the rest of her “miserable life.”

Harmon is barred by the plea agreement from talking about the case. Her usually chatty attorney, Cates, would only say, “This is a very sad case all the way around, and it just needed to end.”

Harmon, now 50, is back in Nevada, friends say.

Mary Burgoon said she’s had a few meals with Harmon and her husband. She said Harmon was unjustly jailed and believes she pleaded guilty only to avoid prison time.

“Wouldn’t you if that was the only way you could get out of there?” Burgoon said. “I do not believe that she did it.”

This content first appear on 9news