As David Klyne stares into the camera he rocks forward on his feet, eagerly gesturing with his hands.

“This is something that’s gripping the research world right now,” the research fellow with the University of Queensland’s school of health and rehabilitation sciences tells 9News.

“The traditional view has been that pain interferes with sleep and that’s certainly true,” he says.

“I think many of us have experienced that, when we might have had an injury, and the following nights may have been fairly poor in terms of sleep.

“However, recent studies, including our own, have flipped that view on its head and we’ve shown that sleep is influencing pain on many levels.”

He says research is now trying to answer the question of ‘how that’s happening?’

“There are many physiological explanations for this – one of those, which is something we’ve worked on, is that changes in sleep alter the immune response,” the research scientist says.

“So, in the case of poor sleep, and it only has to be as little as a few hours lost in one night can trigger cellular pathways within the brain and eventually the entire body to eventually produce inflammation.”

That same inflammation is enhancing pain through stimulating the nervous system.

He says studies have tested people’s pain thresholds before a poor night’s sleep and then retested them after a poor night’s sleep and have shown “there is quite an increase in pain responses” from these people after that poor night’s sleep.

‘It’s a grey area as far as treatment goes because we’re only just starting to understand that sleep does indeed influence pain’

“Between 30 to 50 per cent of the world’s population are affected by chronic pain and of those people with chronic pain 90 per cent experience poor sleep,” he says.

“While that doesn’t give us a direct idea on number as far as how many people have pain because of their poor sleep, it certainly gives us an indication, particularly with a physiological data, that in those cases, perhaps most of them, poor sleep at least on some level is influencing that pain.”

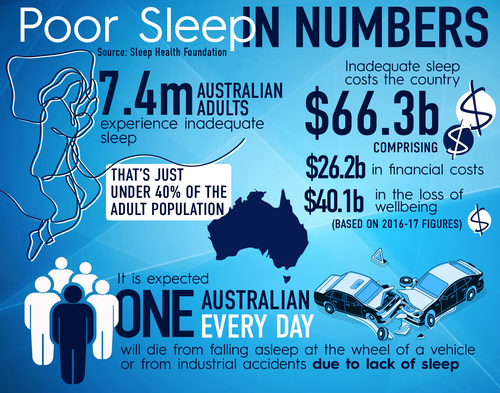

Up to one-third of people experience poor sleep globally with opioids still the most powerful pain relievers. They are frequently prescribed for chronic unrelenting conditions, such as lower back pain.

However, these drugs are accompanied by a number of potentially serious adverse effects including addiction, the cause of 900 deaths per week in the United States alone.

“It’s a grey area as far as treatment goes because we’re only just starting to understand that sleep does indeed influence pain,” Dr Klyne says.

“We don’t always know whether it might be sleep as the primary cause of the pain, or whether it’s sleep being influenced by the pain which is influencing the sleep or other things. The reality is that sleep is driven by so many different factors within our environment, our behaviour, our psychological status that’s really quite difficult.

“It may be even be something along the lines of going and checking up on that potential underlying sleep disorder that you may think you have and actually getting that treated which may enhance your quality of life as far as pain goes throughout the day,” he says.

“An interesting point to this, and I think the most important point, is that this research is hopefully raising awareness to people that there really is physiological explanations for how sleep is enhancing your pain.

“And if people know that, I think they may be more spurred on, to improve their sleep if it’s going to influence or help with their pain levels throughout the day.”

Chronic pain breakthrough

Dr Klyne says one of the main findings that has come from the team’s research is that if you experience poor sleep during the early stage of injuring yourself, you’re more likely to have poor outcome down the track.

“This is critical because we’re now starting to try and answer the question as to whether poor sleep itself is enough to drive that transition from acute to chronic pain,” he says.

‘I would say our findings, which are on the verge right now, will certainly, I think, start to influence advice for practitioners’

“Can it contribute to the development of chronic pain? And that’s what we’re really teasing into now to try and get answers from that because the implications are huge. If we can find more evidence that this is the case, and we can link some things together, we’re really going down the track of opening up new treatments that can be used to prevent chronic pain.”

He says scientists are aware of the relationships between poor sleep and acute pain, and poor sleep and the transition to chronic pain. But what is not known is whether poor sleep is actually causing the chronic pain or if other things are in play.

“We don’t know the mechanisms that are underlying that yet. So, what we’re doing right now, which is a big international effort, between the University of Queensland, and universities within America, is to try and tease out those mechanisms,” he says.

“We’re using very simple experimental models to try and tease out how poor sleep before, after an injury, a long time after, is really driving that transition.

“I would say our findings, which are on the verge right now, will certainly, I think, start to influence advice for practitioners, probably advice for strategies to use for self-management as far as pain goes.”

Dr Klyne and his colleagues began their research in October last year on the back of a US Department of Defence grant.

“In the military of course you cannot always modify your sleep,” he says.

“So, we’re trying to look at other avenues to improve pain or at least prevent the transition from chronic pain using other methods such as exercise, if for whatever instance, you cannot sleep. And of course that can be translated to those who shift work and what not.

“What we’re doing now is taking those theories from our human studies into pre-clinical animal models of chronic pain and we’re seeing whether this is actually true and what are the mechanisms that are driving this transition to chronic pain.”

Developing treatment options

Dr Klyne says as far as specific treatments or developing new treatments it is early days.

“This phase (of the research) is generating the foundational data to guide those new treatments which we have built into this project which will then be tested in following clinical trials hopefully within the next three, four, five years,” he says.

“We’re sort of working backwards in far as research usually goes. We usually try to understand the fundamental mechanisms in cells and then perhaps pre-clinical animal models and if that’s right then we go to humans.

“This is a little bit different, I think it’s perhaps a bit of chance that we’ve found some of these relationships between poor sleep and pain and poor sleep and poor outcome in humans. Now we have to work backwards to try and understand why that is happening.

“As far as people wanting to know more about this, and how they can help themself, there are a lot of different information sources out there. But possibly one of the best ones is mybackpain.org.

“And I say that because back pain is obviously a painful condition and it’s probably one of the most common pain conditions.”

What is back pain and its relation to sleep?

Professor Mark Hutchinson from the Adelaide Medical School agrees.

Professor Hutchinson, who is not involved in Dr Klyne’s study, says of all the burdens of disease across the entire globe the number one is lower back pain.

“This isn’t your classic oh I’ve bent wrong, I’ve lifted something wrong,” Professor Hutchinson tells 9News.

“There is something unique about the lower back which is susceptible for the creation of long-term agony. We do not understand it. The scans come back negative, there’s no pinched disk, there’s no bulging problem.”

He says one of the most commonly reported consequences of acute and chronic pain is disrupted sleep.

“In chronic pain this then creates a vicious descending cycle of misery, because the person is not getting enough sleep, they’re not getting rested, they’re not repairing, which begets more pain… and because they’ve got more pain they can’t sleep,” he says.

“Many of the medicines people are placed on also disrupt sleep. If we could have one intervention that would have the greatest impact in making someone’s life better, even though they continued to have profound pain, is getting a good night’s sleep.

“We don’t have all the answers there but that is a great challenge for the future.”

Professor Lormier Moseley chair of Physiotherapy at the University of South Australia, says a lot of people with back pain – most people with chronic back pain have pain that’s not being caused by damage in their back.

“You speak to anyone with chronic back pain and that can be hard to believe because it feels horrible, Prof Moseley, who was also not involved in Dr Klyne’s study, tells 9News.

“This is where understanding the system is so liberating. The problem is you can’t take a pill to give you understanding of your own pain system.

“You have to learn about it, test it and train it.”

This content first appear on 9news