If you ask her parents, Trisha Sawhney is like any typical 12-year-old girl in so many ways.

“Trisha is a happy-go-lucky child. She has lots of hobbies. She loves TikTok, singing and dancing,” her father Neeraj Sawhney, from Melbourne, says.

“She also loves cooking and baking and wants to start her own YouTube channel to upload her dance and cooking videos.”

But unlike other girls her age, Trisha’s physical disabilities mean she isn’t able to run more than a few metres. At school, her intellectual impairments have stopped her from being able to learn to read or write beyond a basic level.

Trisha and her family’s lives changed in an instant when she was diagnosed with an extremely rare and fatal disease – Aspartylglucosaminuria (AGU) – at the age of five.

The genetic, neurodegenerative disease is so rare Trisha is thought to be the only child in Australia with it. There are about 120 known cases of AGU worldwide.

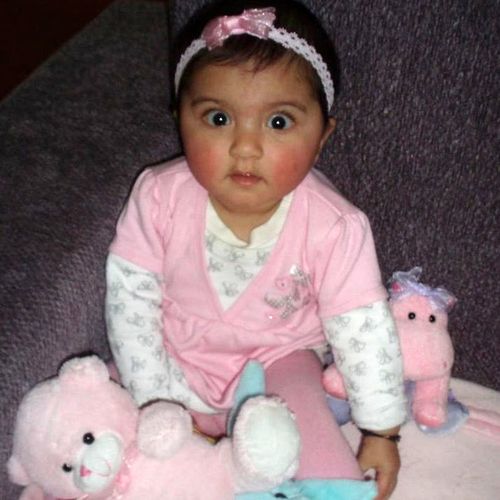

Trisha was born a happy and healthy baby, but was slow to sit and only walked at 18 months.

“Trisha being our first child, we didn’t even realise that she was missing other milestones as well,” Mr Sawhney said.

“It wasn’t until she was four and we enrolled her in kinder that we saw other kids were writing their own names. Trisha couldn’t even write her own name.

“The other kids were able to recite nursery rhymes whereas she couldn’t do that either.”

Now very concerned, Mr and Mrs Sawhney made an appointment with a paediatrician.

At first, doctors thought Trisha might have autism. For almost a year, Trisha went to speech and behaviour classes designed for kids with autism.

Then a urine test ordered by their paediatrician picked up something unexpected, leading the doctor to suspect Trisha’s problems may not stem from autism at all.

“She called my wife and said, ‘I don’t know what it is but I am reading on the internet. I am going to refer you to the children’s hospital’.”

Doctors at the Royal Children’s Hospital confirmed Trisha had AGU. They also delivered the crushing news that there is currently no cure or treatment for the condition.

“We were just devastated. The hospital said there is nothing we can do about it, there is no cure for it.”

The degenerative nature of the disease means Trisha may only live until she is 35.

While Trisha’s disease is rare, Mr Sawhney says he witnessed many families at the hospital going through what they were; torn apart by grief as they tried to help their sick children.

He and his wife were faced with a decision.

“What do we, as parents, want to do about it? We can sit and do nothing and watch our child die. Or we can try to do something and see if we can give her a good life,” he said.

They hit the internet, scouring for information about AGU and contacting any expert who had ever written anything on the topic.

They connected with other families in the US, Canada, Spain, France and Switzerland whose children also have AGU.

A group of 10 families, including Trisha’s, have been avidly following research in clinical trials showing the promising potential for gene replacement therapy in other similar rare genetic diseases.

The treatment involves injecting replacement genes for the mutated ones which cause the disease, with the hope that the cells could be kickstarted into repairing themselves.

“The theory is that around six to nine months later, Trisha could have a full recovery and be back to normal,” Mr Sawhney said.

But the rarity of the disease and its complex nature has made it difficult to convince pharmaceutical companies to conduct a clinical trial for gene replacement therapy in AGU patients.

In Australia, Trisha’s parents have pledged to raise half a million dollars. So far, they have collected almost $90,000 in an online fundraiser.

Families left to shoulder fundraising burden

Nicole Millis is the CEO of Australia’s peak body for patients with rare diseases, Rare Voices Australia.

Ms Millis said for many people living with a rare disease, taking part in a clinical trial can be the only way to access treatment.

But Australia was often seen by drug companies as a less than ideal location to conduct clinical trials, Ms Millis said.

“Pharmaceutical companies are often more inclined to conduct clinical trials in countries where they anticipate they will first market their medicines. Pharmaceutical companies do not typically bring their medicines to Australia first. Internationally, the pharmaceutical industry’s general perception is that Australia is a challenging market with uncertain approval processes,” Ms Millis said.

As was the case with Trisha’s family, it often fell to parents of children with rare diseases to advocate for ground-breaking research.

“There are many examples of parents who have founded or are heavily involved in rare disease support organisations. A number of these organisations are at the forefront of medical research or breakthroughs,” Ms Millis said.

But the families of children with rare diseases shouldn’t be left to shoulder such an enormous burden alone, she said.

“Families living with a rare disease already face many pressures and challenges on a daily basis. It is unfair to rely on individual families, who are already living with the many challenges of rare disease, to feel that they have no choice but to fundraise for research.

“It is important that research work is shared. Governments need to increasingly invest in rare disease research in a way that is coordinated, systemic and sustainable.”

Last February, Rare Voices launched an action plan with the support of the Federal Government and opposition.

The action plan highlighted the need for Federal and State governments to foster an environment conducive to clinical trials taking place in Australia for rare diseases, Ms Millis said.

Rare Voices Australia is also calling for more options to be developed that help Australians living with a rare disease participate in clinical trials, both here and overseas, without patients needing to leave Australia.

As difficult as the fundraising process had been so far, Mr Sawhney said he had no hesitation in going down that path.

“If a medicine was available right now I would sell my property and everything and go and get Trisha some treatment, but right now there is no treatment,” he said.

Mr Sawhney said he hoped their clinical trial would ultimately benefit many children all around the world.

“If this research is successful it will be of benefit to the entire world. We are building on research already done and there will be other researchers who will benefit from this.”

Contact reporter Emily McPherson at emcpherson@nine.com.au.

This content first appear on 9news