“iBlastoids will allow scientists to study the very early steps in human development and some of the causes of infertility, congenital diseases and the impact of toxins and viruses on early embryos – without the use of human blastocysts and, importantly, at an unprecedented scale, accelerating our understanding and the development of new therapies,” Professor Polo said.

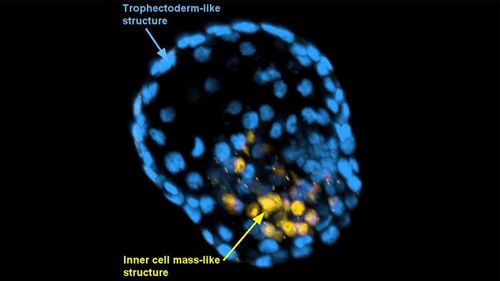

The human skin cells are adapted using “nuclear reprogramming” before being placed on a “jelly” scaffold called an extracellular matrix.

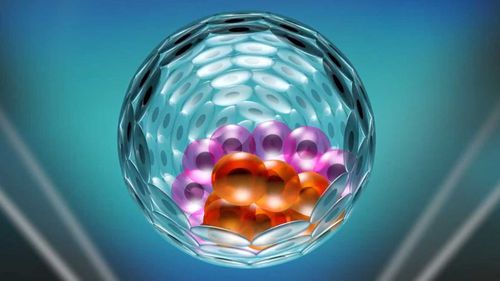

From there, they develop into iBlastoids, which bear a remarkable resemblance in structure to early human embryos.

But unlike an embryo, the iBlastoid is unable to develop more than a few days.

“This is important because it will allow us to study the early days of human development without using human embryos,” Professor Polo said.

“And it will allow us to study many cases of fertility, for example, why many miscarriages happen within the first two weeks of human pregnancy.”

The breakthrough put scientists into an ethical grey area, simply because their invention is not covered by existing guidelines and laws.

But the experiments were conducted within the parameters of Australian law and international guidelines.

Under Australian law, human blastocysts cannot be developed in a lab past the development of something named the primitive streak.

The primitive streak, which appears in blastocysts after 15 days, signals the next stage of the development of embryos.

While no primitive streak developed, the experiments with each iBlastoid were stopped after 11 days anyway.

This content first appear on 9news