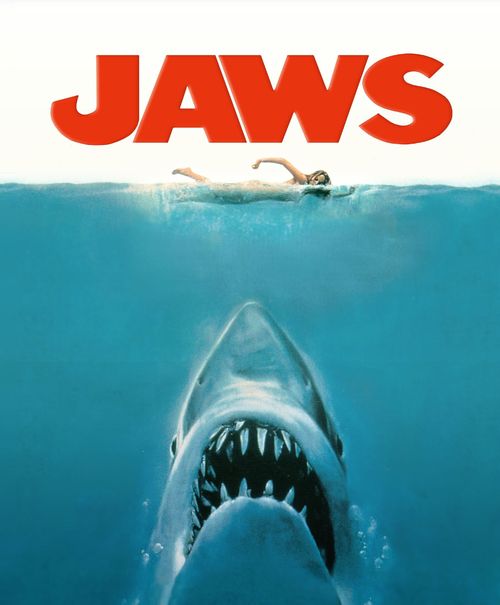

When Steven Spielberg’s Jaws hit theatres in 1975, the blockbuster made people across the world think twice about swimming in the ocean.

The film is based on the Peter Benchley bestselling novel of the same name and follows the reign of terror a blood-thirsty great white shark inflicts on a quiet beach town.

Mr Benchley maintained the iconic film was not inspired by true events, but the circumstances are eerily akin to a real-life tragedy that terrified the US state of New Jersey over a century ago.

It was 1916 and thousands had flocked to the Jersey Shore beaches as a summer heatwave struck ahead of the Fourth of July holiday.

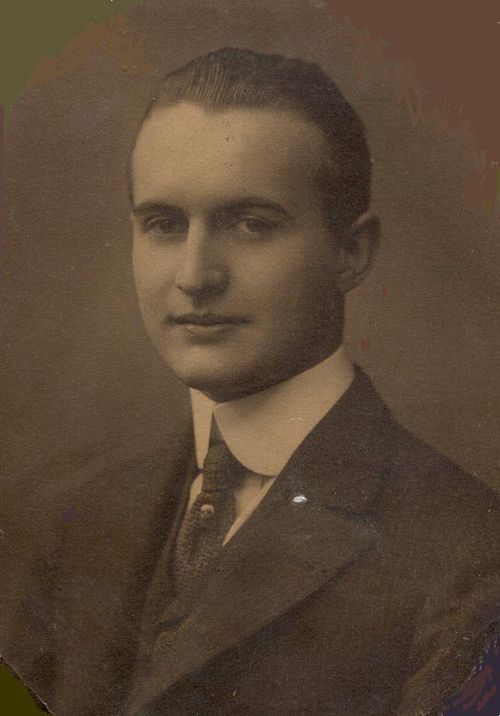

Philadelphia local Charles Vansant was holidaying at Beach Haven, Long Beach Island with his family and decided to go for an early evening swim outside the Engleside Hotel on July 1.

According to news reports at the time, beachgoers saw a large fin emerge from the water near Mr Vansant.

Witnesses desperately tried to get his attention, but could not warn him of the circling marine predator.

The 24-year-old was yanked under water, screaming for help as the large shark clamped down on his left thigh.

Lifeguards managed to get Mr Vansant back to shore with, witnesses claiming the shark followed them in towards the shoreline.

He was carried into the hotel where lifeguards commenced first aid. But the majority of the flesh was missing from his mutilated leg and his femoral artery had been severed.

The holidaymaker quickly bled to death.

The incident sent shockwaves along the east coast and is believed to be the first instance of a fatal shark attack being reported in US news.

There were reports of other large sharks lurking off the New Jersey coast, but authorities watered down the seriousness and beaches remained open.

“Despite the death of Charles Vansant and the report of two sharks having been caught in that vicinity recently, I do not believe there is any reason why people should hesitate to go swimming at the beaches for fear of man-eaters,” State Fish Commissioner of Pennsylvania James M. Meehan wrote in the Philadelphia Public Ledger.

Five days later, Charles Bruder went for a swim during his lunch break from the Sussex and Essex Hotel in Spring Lake – 83 kilometres north of the first attack.

This was something the bellhop did routinely and with the sweltering heat, the 27-year-old didn’t think twice about venturing out past the roped swimming lines.

Mr Bruder got 120 metres out when a shark latched onto his abdomen and tried to pull him under.

A woman on shore heard the man screaming and summoned two lifeguards who jumped in a boat to save him.

Mr Bruder was able to pull himself into the lifeboat but with both his legs now missing from the knees down, he lost consciousness as blood continued to gush out of him.

A nearby doctor tried to treat Mr Bruder once he was brought to shore but the young man died on the sand.

Despite this being the second attack in less than a week, authorities drummed it up to an unfortunate coincidence due to “an unusual hunger”.

As the two attacks gained national media attention swimmers were still (cautiously) entering the New Jersey waterways to escape the intense summer heat, despite many now arguing the two attacks were by the same creature.

On July 12, Lester Stilwell was swimming with friends off Wyckoff Dock in Matawan Creek, located another 45 kilometres north of Spring Lake and further inland than the first two attacks.

The 11-year-old had also brought his dog along when the group spotted what they thought was “an old black weathered log” floating nearby.

According to witnesses, a large fin then emerged and something grabbed onto young Lester and pulled him under.

The boys raised the alarm and local man Watson Fisher jumped in to help them.

Lester had epilepsy and Mr Fisher thought he may have been having a seizure, but when the 24-year-old managed to locate the boy’s lifeless body, the shark tore into his right thigh.

As panic spread along the shore of Matawan Creek, another boy was attacked at a separate beach 30 minutes later.

Joseph Dunn was visiting his aunt at Cliffwood Beach, just 2.5 kilometres north of Matawan Creek.

News hadn’t reached Cliffwood about the Matawan Creek attacks and Joseph, 14, was swimming with his brother and a friend when Thomas Cottrell, a fisherman who heard the shark warning on his radio yelled at them to get to shore.

As Joseph swam frantically to get out of the water, a shark latched onto his left leg and pulled him under.

His brother and friend fought with the shark, managing to free Joseph whose leg had been stripped nearly bare.

Watson Fisher died from his injuries on the operating table and young Lester Stilwell’s body was found 46 metres upstream from Wyckoff Dock on July 14.

Joseph Dunn had to have his leg amputated and was released from hospital on September 15.

Days before the Matawan Creek attacks, locals reported they saw a 2.4 metre shark but authorities said it was unlikely that far inland and brushed it off as panic over the recent attacks.

The town folk were angry and wanted to hunt the shark, offering a reward for its death and even filling the creek with dynamite hoping to blow it up.

President Woodrow Wilson held Cabinet meetings about the attacks and local governments erected chicken wire barriers in the water in an effort to stop sharks coming near swimmers.

It has never been confirmed if it was the same shark that attacked the five victims, but a short time later, local fisherman Michael Schleisser captured a 2.5 metre great white just outside the creek.

Seven kilograms of human flesh were found during its dissection, including bones believed to belong to a child.

There were no more attacks on swimmers along the Jersey Shore that summer and authorities believe Mr Schleisser’s catch was the one responsible.

This content first appear on 9news