Key Points

- The Biden administration brings a starkly different vision for U.S. international engagement, including global health, compared to the “America First” foreign policy doctrine of its predecessor.

- At the top of the agenda is addressing COVID-19, re-engaging with the global community more broadly, and pursuing a stepped-up emphasis on global health security.

- The administration has already taken several actions including: releasing a National Strategy on COVID-19 and Pandemic Preparedness; issuing a National Security Memorandum and Executive Order on U.S. global leadership on COVID-19 and global health security; restoring funding for and membership in WHO; joining COVAX; and rescinding the Mexico City Policy. It has also proposed several other actions, including some that require Congressional support.

- Yet the extent to which the administration will seek to champion core global health programs beyond COVID-19 and preparedness remains unknown, as does the level of support from Congress, given the pressures of COVID-19 and economic strain at home. The stakes are even higher now, given the emergence of new COVID-19 variants and the slow roll-out of vaccines.

- Among the many key policy issues and outstanding questions ahead are the following:

- How the U.S. will be received on the global stage;

- How best to balance COVID-19 needs at home and abroad;

- How robust will U.S. support for global COVID-19 vaccine access be;

- Whether global health security will become a dominant frame for U.S. global health engagement;

- How much room there will be to address the unfinished business of global health, including the effects of COVID-19 on core programs;

- The balance between bilateral and multilateral U.S. health investments;

- How the U.S. will approach WHO reform;

- How far will the administration go in its support for global family planning and reproductive health and how will it withstand partisan push back in Congress; and

- Whether the bipartisan consensus regarding global health funding can be maintained.

Introduction

On January 20, President Biden took the oath of office, in the midst of a pandemic that is raging out of control across the U.S. and throughout the world. Biden brings a starkly different vision for U.S. international engagement, including global health, compared to the “America First” foreign policy doctrine of his predecessor. At the top of the Biden administration’s agenda is addressing the COVID-19 pandemic at home and abroad, re-engaging with the global community more broadly, and pursuing a stepped-up emphasis on global health security. The administration has also signaled more general support for U.S. global health programs. In the first days of office, the Biden administration has already put into place policies, strategies, and staff with expertise in these areas and has indicated that more actions are to come. Some of the proposed actions can be taken via executive authority while others will require the cooperation and approval of Congress. While Congress has provided emergency support for global COVID-19 relief, including for health, and demonstrated some appetite for bolstering U.S. global health security, it is unclear how the new administration’s proposals will fare given broader partisan gridlock and the strains on the U.S. economy. In addition, the extent to which the Biden administration will seek to champion core U.S. global health programs, or change the broader U.S. global health architecture, beyond an expanded focus on global health security, remains unclear. It’s also possible that even maintaining support for the current U.S. global health portfolio could be difficult, given the extreme domestic pressures related to COVID-19. With this as the backdrop, we provide an overview of the Biden administration’s COVID-19 and global health actions to date, as well as likely ones on the horizon, and identify key policy issues and outstanding questions ahead. The stakes are particularly high, given the emergence of variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, that appear to spread more easily and the slow roll-out of vaccines.

The Biden Administration’s Global Health Agenda

Both on the campaign trail and during his first days of office, Biden has made it clear that he seeks to re-embrace international engagement, including on health, with COVID-19 as a top focus. Biden has made re-embracing the global community a key policy goal for his administration. This represents a major departure from the Trump administration’s posture, which saw the U.S. sit out the international response to COVID-19, withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord, and withhold funding for the World Health Organization (WHO), while initiating the process of withdrawing from WHO membership. By contrast, the Biden administration has critiqued this approach, stating that “America’s withdrawal from the international arena has impeded progress on a global COVID-19 response and left the United States more vulnerable to future pandemics. U.S. international engagement to combat COVID-19, promote health, and advance global health security will save lives, promote economic recovery, and build better resilience against future biological catastrophes.” The new administration has already taken several actions on this front, including issuing a National Strategy for the COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness; a National Security Memorandum on “United States Global Leadership to Strengthen the International COVID-19 Response and to Advance Global Health Security and Biological Preparedness”; and an Executive Order on “Organizing and Mobilizing the United States Government to Provide a Unified and Effective Response to Combat COVID-19 and to Provide United States Leadership on Global Health and Security”. It has also proposed several other actions, some of which are dependent on Congressional support (see Table). Given the widespread nature and ever-evolving threat from COVID-19, including the rise of variants that may spread more easily, it appears likely that addressing the pandemic and its many effects will occupy much of the global health policy attention within the administration for the foreseeable future.

Among the new administration’s first actions was announcing that the U.S. would remain a WHO member and continue funding the organization. Just as the COVID-19 pandemic was devasting much of the world, including the U.S., Trump announced last April that he was putting a hold on U.S. funding to WHO, pending investigation of its COVID-19 response, and formally notified the United Nations in July of last year that the U.S. would withdraw from WHO membership (effective one-year later per U.S. law). Historically, the U.S. had been the largest funder of the WHO, providing $400 million to $500 million in funding to the organization each year, and had played a leadership role in the organization. Withholding funds and initiating a process to withdraw from the world’s international health organization had both practical and symbolic effects. Biden campaigned on retracting the Trump administration’s decision and restoring funding, actions taken on day one of the Biden administration. This included formal communication with the United Nations and WHO about the U.S. intent to remain a member of WHO and continue funding; a call by the Vice President to the WHO Director General; and, as specified in the National Security Memorandum on COVID-19 and global health security, intent to work with the WHO to strengthen and reform the organization to enhance its ability to respond to COVID-19, global health, and future pandemics, a goal shared by other Member States.

The administration also announced that the U.S. would support the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator and join the COVAX Facility and commit to multilateralism and the international COVID-19 response. These actions were announced on January 21, 2021, and directed by the President in the National Security Memorandum, as part of the new administration’s package of COVID-19 policies. By contrast, under the Trump administration, the U.S. had been one of the only countries not to formally participate in the ACT Accelerator or COVAX, or the broader international response. While Congress had provided emergency funding to Gavi in support of COVID-19 vaccine access in low- and middle- income countries, the absence of U.S. leadership in these initiatives under the Trump administration marked a break from how the U.S. responded to most other recent global health emergencies. The Biden administration also said it would develop a framework for donating surplus vaccines, once there is sufficient supply in the U.S., to countries in need, including through COVAX. The Trump administration had included similar language in a December 2020 Executive Order, which was largely focused on ensuring American access to vaccines. In addition, the Biden administration has said it would seek funding from Congress to strengthen and sustain other multilateral initiatives involved in addressing COVID-19, including the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI); Gavi; and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria (Global Fund). Notably, the plan for a stepped-up U.S. international COVID-19 response explicitly includes an emphasis on “reducing racial and ethnic disparities and seeing to the needs of marginalized and indigenous communities, women and girls, and other groups.” Finally, the new administration announced it was re-entering the Paris Climate Agreement, as part of its major commitment to address climate change which it sees as a driver of health threats.

In addition, marking a significant break from the prior four years, the Biden administration has rescinded the Mexico City Policy and seek to restore funding for UNFPA, and has said it would recommit to addressing sexual and reproductive health and rights. First announced in 1984 by the Reagan administration, the Mexico City Policy (called “Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance” by the Trump administration) has been rescinded and reinstated by subsequent administrations along party lines, having been in effect for 21 of the past 36 years. The policy requires foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to certify that they will not “perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning” using funds from any source (including non-U.S. funds) as a condition of receiving U.S. government global family planning assistance and, under the Trump administration, most other U.S. global health assistance. This marked an unprecedented expansion of the policy. On January 28, President Biden issued a Presidential Memorandum announcing that he was rescinding the policy, effective immediately, and it would no longer be applied to existing awards or any future ones. In addition, the Memorandum also announced that the administration would take the necessary steps to restore funding to UNFPA. The Trump administration had withheld Congressionally-appropriated funding from UNFPA for four years, by invoking the Kemp-Kasten amendment. In rescinding the Mexico City Policy and moving to restore UNFPA funding, the Biden administration stated that it was U.S. policy “to support women’s and girls’ sexual and reproductive health and rights in the United States, as well as globally,” and also announced that it would withdraw from the Geneva Consensus Declaration, an October 2020 statement crafted and signed by the U.S. and 32 other countries, meant to enshrine the former administration’s values and principles related to women’s health, abortion in particular, and family, in the international sphere. Collectively, these actions signify a significant turn from the Trump administration’s approach which had sought to impose restrictions, limit funding, and alter international and bilateral agreements to reflect these views.

As part of his COVID-19 “American Rescue” plan, Biden has said he would seek $11 billion for global COVID-19 efforts. The American Rescue Plan includes $11 billion to support “the international health and humanitarian response; mitigate the pandemic’s devastating impact on global health, food security, and gender-based violence; support international efforts to develop and distribute medical countermeasures for COVID-19; and build the capacity required to fight COVID-19, its variants, and emerging biological threats.” To date, through prior COVID-19 relief bills, Congress has provided approximately $7.5 billion to overall global COVID-19 efforts. Of this, $5.2 billion has been allocated for global health, primarily for vaccine support ($4 billion); to date, no funding has been provided to address the primary or secondary impacts of the pandemic on existing global health programs. At this time. only limited detail on the administration’s $11 billion request is available and it is unclear if it will garner enough support from members of Congress.

| Action | Requires Administrative or Congressional Action? |

Status |

| Restore the National Security Council’s Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense | Administrative | √ |

| Rescind the Mexico City Policy | Administrative | √ |

| Restore funding to UNFPA | Administrative | √ |

| Release a National COVID-19 Response Strategy, including a strategy for international engagement | Administrative | √ |

| Restore funding to WHO and reverse Trump administration decision to withdraw from WHO membership | Administrative | √ |

| Support the ACT-Accelerator and Join COVAX | Administrative/

Congressional* |

√ |

| Create position of Coordinator of the COVID-19 Response and Counselor, reporting to the President | Administrative | √ |

| Develop a diplomatic outreach plan led by the State Department to enhance the US response to COVID-19, including through the provision of support to the most vulnerable communities. | Administrative** | √ |

| Provide $11 billion to support “international health and humanitarian response,” including efforts to distribute countermeasures for COVID-19, build capacity required to fight COVID-19, and emerging biological threats | Congressional | Proposed |

| Ensure adequate, sustained U.S. funding for global health security | Congressional | Proposed |

| Expand U.S. diplomacy on global health and pandemic response, including elevating U.S. support for the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) | Administrative | Proposed |

| Call for the creation of permanent international catalytic financing mechanism for global health security and work with international financial institutions, including multilateral development banks, to promote support for combating COVID-19 and strengthening global health security | Administrative | Proposed |

| Call for creation of a Permanent Facilitator within the Office of the United Nations Secretary-General for Response to High Consequence Biological Events | Administrative | Proposed |

| *Depending on the details of the administration’s proposal to support the ACT-Accelerator and join COVAX, Congressional approval may be required. **The National Security Memorandum requires the Secretary of State, in consultation with the Secretary of HHS, the Representative of the United States to the United Nations, the Administrator of USAID, and the Director of the CDC, to develop this plan within 14 days or as soon as possible. SOURCES: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/National-Strategy-for-the-COVID-19-Response-and-Pandemic-Preparedness.pdf; https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/21/national-security-directive-united-states-global-leadership-to-strengthen-the-international-covid-19-response-and-to-advance-global-health-security-and-biological-preparedness/; https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/executive-order-organizing-and-mobilizing-united-states-government-to-provide-unified-and-effective-response-to-combat-covid-19-and-to-provide-united-states-leadership-on-global-health-and-security/; https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/28/memorandum-on-protecting-womens-health-at-home-and-abroad/. |

||

The administration has also begun to institute a new structure for the White House and National Security Council (NSC) Staff, including re-establishing the NSC Directorate on Global Health Security and Biodefense. By all indications, Biden and his transition team see global health, especially as it relates to the pandemic, as an integral part of their foreign policy agenda. He re-established, via Executive Order, the NSC Directorate on Global Health Security and Biodefense (originally created during the Obama administration and charged with overseeing pandemic response but shuttered by the Trump administration in 2018), and named a COVID-19 Coordinator to oversee a whole of government approach to pandemic response. Further, Biden has already appointed or nominated advisors and key staff with experience in global health and infectious disease threats and/or a strong belief in the importance of international engagement, including his Chief of Staff (Ron Klain); Chief Medical Advisor (Tony Fauci); Secretary of State (Anthony Blinken); National Security Advisor (Jake Sullivan); NSC Senior Director for Global Health Security and Biodefense (Beth Cameron); CDC Director (Rochelle Walensky); USAID Administrator (Samantha Power); and the President’s Malaria Coordinator (Raj Panjabi). Biden will now look to nominate or appoint persons to fill other critical U.S. global health positions including the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Director of the Office of Global Affairs, and USAID’s Assistant Administrator for Global Health.

Indeed, scaling up the U.S. global health security effort and apparatus is shaping up to be a signature global health focus of the Biden agenda, one which already has some bipartisan support in Congress. In the administration’s National COVID-19 strategy and elsewhere, Biden and key staff have discussed the need for significant changes in the level and scope of U.S. support for global health security programs to reduce the chances of repeating our current pandemic crisis in the future. This includes the Executive Order on “Organizing and Mobilizing the United States Government to Provide a Unified and Effective Response to Combat COVID-19 and to Provide United States Leadership on Global Health and Security” and National Security Memorandum on “United States Global Leadership to Strengthen the International COVID-19 Response and to Advance Global Health Security and Biological Preparedness. Global health security programs, which help countries build their capacities to prevent, detect, and respond to emerging disease outbreaks, have long been supported by the U.S. government and were maintained during the Trump administration, but have suffered from limited and sporadic funding and bouts of attention only during times of crisis. COVID-19 has precipitated urgent attention to this area that is likely to result in greatly expanded U.S. ambitions, with key Biden staff outlining such a vision for months and referencing public health as a permanent U.S. national security priority that will be an initial and major focus for the administration. There has also been some Congressional support for doing more, including a bipartisan proposal released last year from Senators Risch, Murphy, and Cardin to enhance strategic planning, strengthen interagency coordination, and grow U.S. diplomatic presence in global health security efforts.

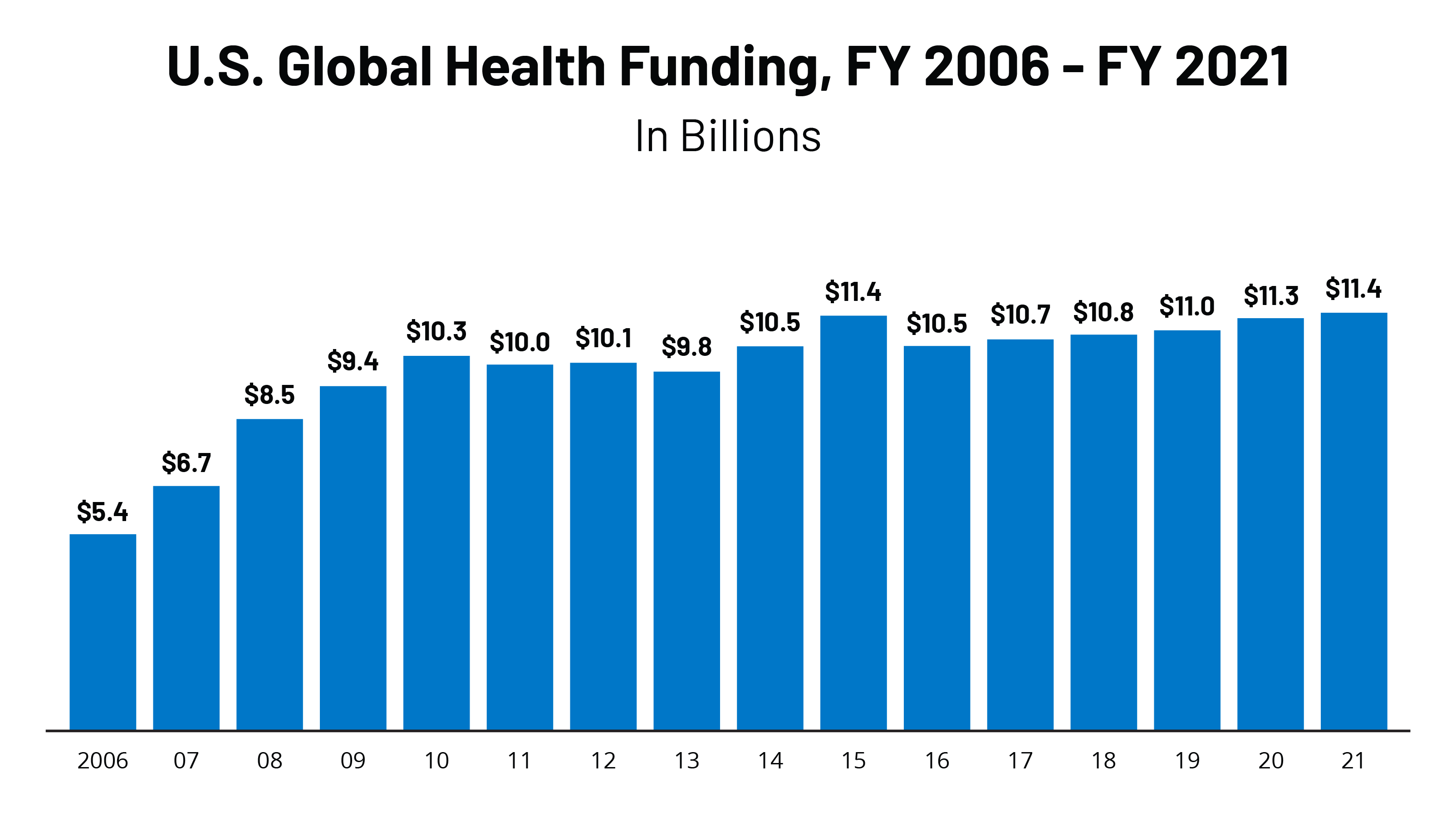

The administration has expressed support for other core U.S. global health efforts, including PEPFAR, but it is not yet known how prominently they will figure into its agenda or how they will be connected to the broader global health security push; at the same time, there remains much unfinished business in improving the health of those in low-and middle-income countries. The U.S. is the largest funder of global health efforts in the world, operating programs in more than 70 countries; 80% of its funding is provided through bilateral programs and the remainder through multilateral efforts. These programs (including PEPFAR and the Global Fund) have not only been credited with saving millions of lives, they have been shown to contribute to global health security efforts, including during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Yet U.S. funding for global health has largely been stagnant for years, despite the unfinished business that remains (although Trump sought significant and unprecedented cuts each year in office, these were rejected time and again by Congress). Within the U.S. global health portfolio, PEPFAR represents the largest component, and one which has been credited with saving millions of lives. During his time as a Senator and Vice President, Biden supported U.S. global health programs broadly, including as a sponsor of PEPFAR’s first re-authorization and as recently as last month saying he would work to expand support for PEPFAR. As mentioned above, the administration has said it would seek more funding for the Global Fund and Gavi, given their direct role in responding to the pandemic, and seek to mitigate the secondary impacts of COVID-19 and strengthen bilateral U.S. programs in HIV, TB, malaria, and other health systems strengthening efforts. Biden’s strategy notes that in addition to the immediate response needs the pandemic is a moment the U.S. has an opportunity to “reset and drive action to advance the Sustainable Development Goals, make gains toward achieving Universal Health Coverage.” But it is not yet clear if and to what extent the administration will seek to increase funding for, or make fundamental changes to, the core U.S. bilateral global health programs, or seek to shift the balance of its investments between bilateral and multilateral support to perhaps move toward these bolder, broader goals. Given that PEPFAR is largest component of the U.S. global health response and is primed for an update to its goals and direction, Biden’s choice to fill the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator position and his first global health budget request will be especially significant and offer an indication of his vision for addressing HIV globally while also signaling his approach to broader U.S. global health engagement.

Key Questions Ahead

The global health agenda and overall approach to international engagement espoused by the Biden administration is a clear break from the four year “America First” approach under Trump. It also marks a potential departure from prior administrations, given its heavy focus on global health security in light of the devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, a focus which could have lasting effects on the U.S. approach to global health. Whether or not Biden will be able to achieve the broad goals he has outlined is uncertain, and there are likely to be checks on his ambitions. It is also unclear how existing global health programs supported by the U.S. will figure into these plans. Among key questions to consider are the following:

- How will the U.S. be received on the global stage? As the U.S. seeks to re-engage globally, how will the international community respond, especially given the changing and in some cases more prominent roles played by others, including China and the European Union? Is there a unique window of opportunity for the Biden administration to use its diplomatic power to rally countries and institutions in support of the global COVID-19 response, particularly around vaccines? Will vaccine aid become a new version of soft power? Or has the dynamic of U.S. leadership permanently shifted, given the retreat during the Trump years, and the ongoing challenges of battling COVID-19 at home? Will the circumstances of a post-COVID world require a new way for the U.S. to engage internationally on global health issues, or will relations revert back to the pre-COVID state of affairs?

- How best to balance COVID-19 needs at home and abroad? Despite the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic has thrown into stark relief the interconnectedness of the world, the U.S. remains in the throes of a domestic health and economic crisis. There may emerge competition – for both resources and vaccine supply – between domestic and global needs. How much recognition will there be that U.S. safety is inextricably linked to success in addressing the global pandemic? Can a broader, global response be pursued by the Biden administration in this context? Will it face push back by Congress or a public that still awaits a return to some sense of normalcy?

- How robustly will the administration support global COVID-19 vaccine access, including COVAX? Given that vaccinating as many people as possible around the world is the surest way to bring the pandemic under control, ensuring access to vaccines will be pivotal for U.S. progress on many domestic and international policy priorities. The U.S. has now stated an intention to join COVAX, but under what terms? Will it join as a self-financing country and purchase vaccines itself through this mechanism, and/or support the COVAX Advance Market Commitment in support of low- and middle- income country access? Exactly when and how will the U.S. government approach donating excess doses, through COVAX or otherwise? Given that successful vaccination programs rely not just on doses and supplies but also workers, PPE, and other capabilities, will support for delivery and health systems more broadly also be incorporated into the U.S. response?

- Will global health security become a dominant frame for U.S. global health engagement going forward? U.S. global health programs address a broad array of health challenges – from HIV, to maternal and child mortality, to neglected tropical diseases and many more. Will contributions to preparedness and security become the overarching paradigm for thinking and talking about U.S. global health programs? If so, will this help to strengthen existing global health programs or create unintended consequences that could hinder their efforts? How might the U.S. define the focus and the scope of its health security approach? And, can the administration work with Congress to bring an end to the boom and bust cycles for global health security with longer-term commitments and predictable funding? Or, will this be once again forgotten when the world is able to move past COVID-19?

- What about the unfinished business of global health? Is there room – beyond COVID-19 and global health security – to expand U.S. global health efforts and how aggressively will the new administration seek to do so? Given the enormity of COVID-19 it is understandable the Biden administration’s immediate focus is on the pandemic and global health security, but what will happen to the broader U.S. global health agenda? Will there be room to set ambitious new goals for core U.S. global health programs? Will the new administration double down in these core areas as part of a push to shore up global health security? With COVID-19 exposing the weaknesses of health systems and preparedness around the world, will there be a reexamination of the balance of U.S. global health support between vertical, disease-focused programs and broader, health systems strengthening? If so, what risks could this pose and how can the contribution of these programs to health systems strengthening and global health security be better measures, captured, and built upon? And, how can the new administration address the impacts of COVID-19 on existing U.S. supported health programs, as well as its secondary effects on the health and economies of low-and middle-income countries? To date, for example, none of the core U.S. global health programs (beyond global health security) have received any supplemental support to address the impacts of and setbacks due to COVID-19.

- What is the right balance between bilateral and multilateral U.S. health investments, both for COVID-19 and global health more broadly? How should the administration’s $11 billion global COVID-19 relief request be channeled between its own programs and international response mechanisms? What about core U.S. global health investments, which have been impacted by COVID-19 but not yet received any emergency support? Are there ways to better coordinate between bilateral and multilateral health efforts, particularly PEPFAR and the Global Fund, to create greater impact? As the Global Fund and GAVI increasingly phase-down and end their support for middle income countries, what is the role of the U.S. government in helping to meet the needs of those living in these countries who continue to face access barriers and suffer adverse health outcomes? How will COVID-19 change these considerations?

- What will be the administration’s approach to reforming WHO and other international institutions? 2021 will mark the beginning of a process to reckon with the weaknesses in international and domestic systems that were laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic. How much will the administration push, for example, for significant change to multilateral institutions such as WHO or support attempts to revamp existing international health agreements such as the International Health Regulations? How will the tension between the U.S. and China, that played out so clearly in the pandemic, affect diplomacy around WHO reform?

- How far will the administration go in its support for global family planning and reproductive health and how will it withstand partisan push back in Congress? How forceful will the new administration be on this front? Given that family planning and reproductive health is still likely be subject to fierce partisan battles in Congress, how will the new administration navigate and address these tensions? Can the U.S. move past the constant log-jam and ping pong nature of the Mexico City Policy?

- Finally, how will the administration grapple with the reality of having only the slimmest of Democratic majorities in the Senate in seeking to achieve its COVID-19 and global health agenda? Undergirding much of a Biden agenda on COVID-19 and global health will be the need to maintain bipartisan, Congressional support. Will the bipartisan consensus that has characterized much of U.S. global health prevail, or will there be a turn toward austerity and pressure to cut foreign aid? Will exceptions be made for the global COVID-19 response? How can the Biden administration navigate support for global health across the aisle as it seeks an expansion domestic agenda? (as we’ve seen in the past during periods of economic distress and rising deficits)?

This is very educational content and written well for a change. It’s nice to see that some people still understand how to write a quality post!

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I know it was my choice to read, but I actually thought you have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could fix if you werent too busy looking for attention.

We are really grateful for your blog post. You will find a lot of approaches after visiting your post. Great work

Wow! Such an amazing and helpful post this is. I really really love it. It’s so good and so awesome. I am just amazed. I hope that you continue to do your work like this in the future also.

I have to search sites with relevant information on given topic and provide them to teacher our opinion and the article.