Even as the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out is accelerating across the country, the public health and economic effects of the pandemic continue to affect the well-being of many Americans. The American Rescue Plan includes additional funding not only to address the public health crisis of the pandemic, but also to provide economic support to many low-income people struggling to make ends meet. Millions have lost jobs or income in the past year, making it difficult to pay expenses including basic needs like food and housing. These challenges will ultimately affect people’s health and well-being, as they influence social determinants of health. This brief provides an overview of social determinants of health and a look at how adults are faring across an array of measures one year into the pandemic.

What are social determinants of health?

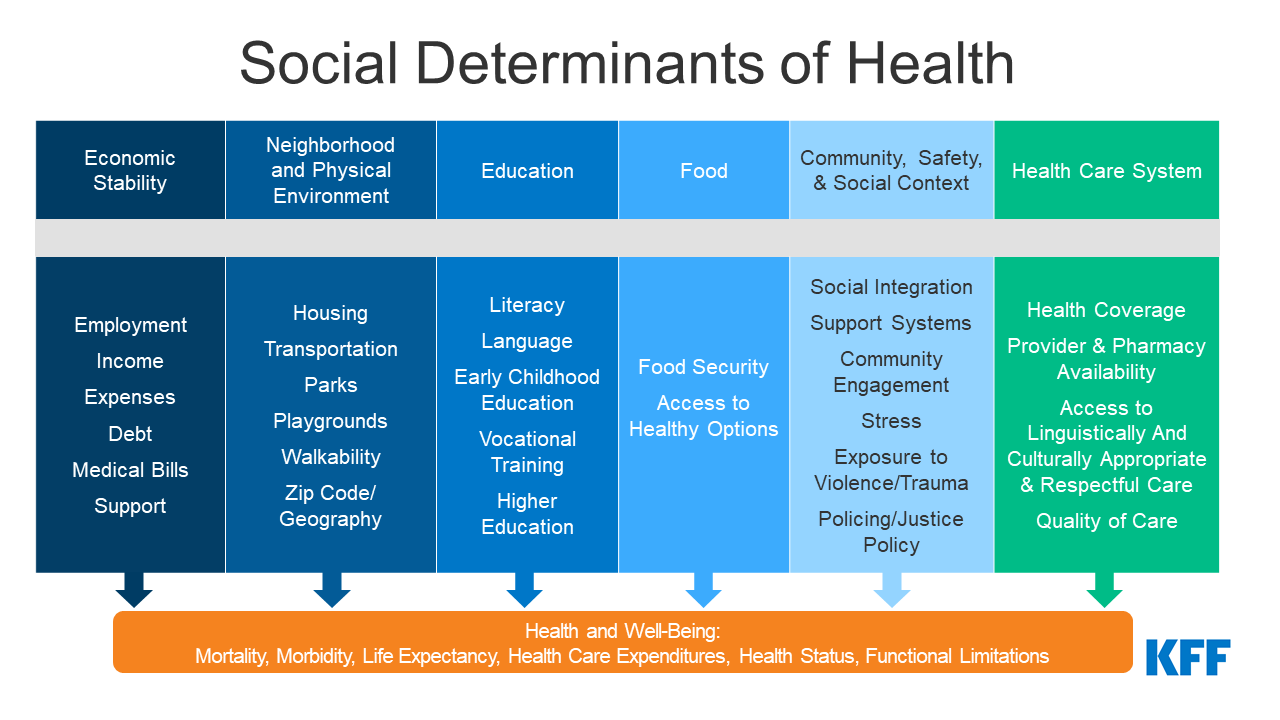

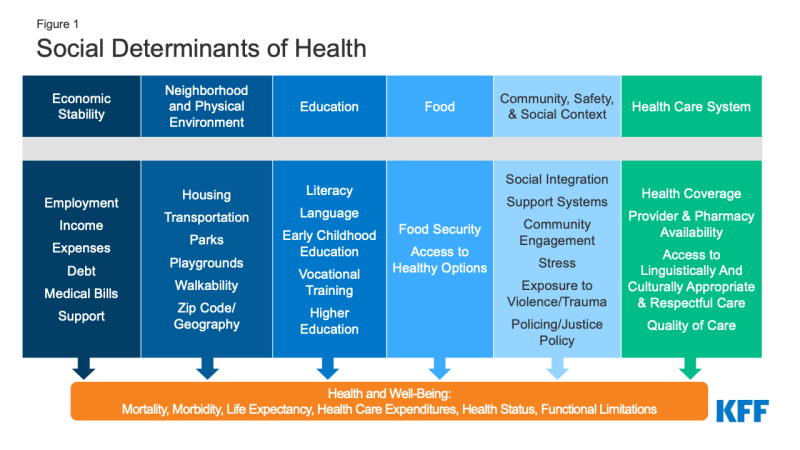

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. They include factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care (Figure 1).

Though health care is essential to health, research shows that health outcomes are driven by an array of factors, including underlying genetics, health behaviors, social and environmental factors, and financial distress and all of its implications. While there is currently no consensus in the research on the magnitude of the relative contributions of each of these factors to health, studies suggest that health behaviors and social and economic factors are the primary drivers of health outcomes, and social and economic factors can shape individuals’ health behaviors. There is extensive research that concludes that addressing social determinants of health is important for improving health outcomes and reducing health disparities. Prior to the pandemic there were a variety of initiatives to address social determinants of health both in health and non-health sectors. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing health disparities for a broad range of populations, but specifically for people of color.

How are adults faring across a range of social determinants of health during the pandemic?

Across a wide range of metrics, large shares of people are experiencing hardship. The Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey was designed to quickly and efficiently collect and compile data about how people’s lives have been impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. For this analysis we looked at a range of measures over the course of the pandemic. Since the start of the pandemic, shares of people reporting hardship across various measures has been relatively constant, with a slight peak for the December reporting periods (Figure 2). For the most recent period, February 3-February 15:

- Nearly half adults (47%) reported that they or someone in their household had experienced a loss of employment income, and one in five applied for Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefits since March 2020;

- More than six in ten (61%) adults reported difficulty paying for usual household expenses in the past 7 days, and 27% used credit cards or loans to meet household spending needs;

- More than 7% of adults had no confidence in their ability to make next month’s housing payment (across renters and owners), and 11% reported food insufficiency in their household;

- Three in ten (30%) adults reported delaying medical care in the last four weeks due to the pandemic and 39% reported symptoms of depression or anxiety.

Black and Hispanic adults fare worse than White adults across nearly all measures, with large differences in some measures. For example, just over 75% of Black and Hispanic adults reported difficulty paying household expenditures compared to 53% of White adults; about 13% of Black and Hispanic adults reported no confidence in their ability to make next month’s housing payment compared to 5% of White adults, and 20% of Black adults and 18% of Hispanic adults reported food insufficiency in the household compared to 8% of White adults. While these disparities in social determinants of health existed prior to the pandemic, the high current levels among certain groups highlights the disproportionate burden of the pandemic on people of color.

While variation across age and gender was not as stark, in general younger adults (ages 18 to 44) and women fared worse on most measures compared to older adults and men. For example, higher shares of younger adults and women reported symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as difficulty paying for usual household expenses. Higher shares of younger adults reported food insufficiency in their household and higher shares of women reported delaying medical care in the last four weeks due to the pandemic. As with race/ethnicity, some of these differences in social determinants were present even before the pandemic, but understanding them in the context of heightened levels of need over the past year highlights these differences and who may benefit most from assistance.

Across most measures, adults with children in their household fared worse compared to overall adults. For example, 53% of adults with children in the household experienced loss of employment income in the household compared to 47% of adults overall, and just over two-thirds of adults with children in the household reported difficulty paying for household expenses compared to the overall population of 61%. Notably, adults in households with children were more likely to report food insufficiency than the general population.

What to watch going forward

The American Rescue Plan provides $1.9 trillion in funding to address the ongoing health and economic effects of the pandemic. Some of the provisions that provide key economic support for individuals include direct stimulus payments to individuals, an extension of federal unemployment insurance payments, a child tax credit of up to $300 per child per month from July through the end of the year, additional funding to address food insecurity, emergency rental assistance, and emergency housing vouchers. In terms of provisions to address COVID and health care, the plan provides additional funding for The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) related to administration and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines as well as increased funding for testing and tracing coronavirus infections as well as testing supplies and personal protective equipment. The plan includes provisions to make health insurance more affordable by temporarily expanding and increasing Marketplace subsidies and fiscal incentives to encourage states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion to do so.

Additional funding and policy changes could lead to improvements in many of the indicators related to economic security and health access highlighted in this brief. In addition, as more people receive the vaccine, state restrictions may continue to ease and economic activity may increase. Future data from the Pulse survey may reflect these changes. Many of the problems and disparities highlighted in this data existed prior to the pandemic, but the economic crisis has heightened the level of challenge faced by many. Changes to address COVID-related and underlying economic security issues tied to poverty, access to food and housing have direct links to improvements in health and can also help to address health disparities. While addressing these underlying social determinants of health can be difficult and would likely require significant government spending, we are unlikely to make significant progress in narrowing health inequities without doing so.