Key Takeaways

Community health centers are a national network of over 1,300 safety-net primary care providers, serving more than 31 million patients in 2023. They are located in medically underserved urban and rural communities and serve all patients regardless of their ability to pay, providing a range of medical, behavioral, and supportive services. This brief reports on health center patients, services, experiences, and financing in 2023 and analyzes changes from 2019 (pre-pandemic) through 2023 using data from the Uniform Data System (UDS), to which all health centers are required to report annually, and the 2022 Health Center Patient Survey. Key takeaways include the following:

- The health center patient population increased to over 31 million patients in 2023, up slightly from 30.5 million in 2022. While the number of children served at health centers increased to over 9.1 million in 2023, this remains slightly lower than the 9.2 million served pre-pandemic in 2019, possibly reflecting overall reduced utilization of primary and preventive services among children on Medicaid.

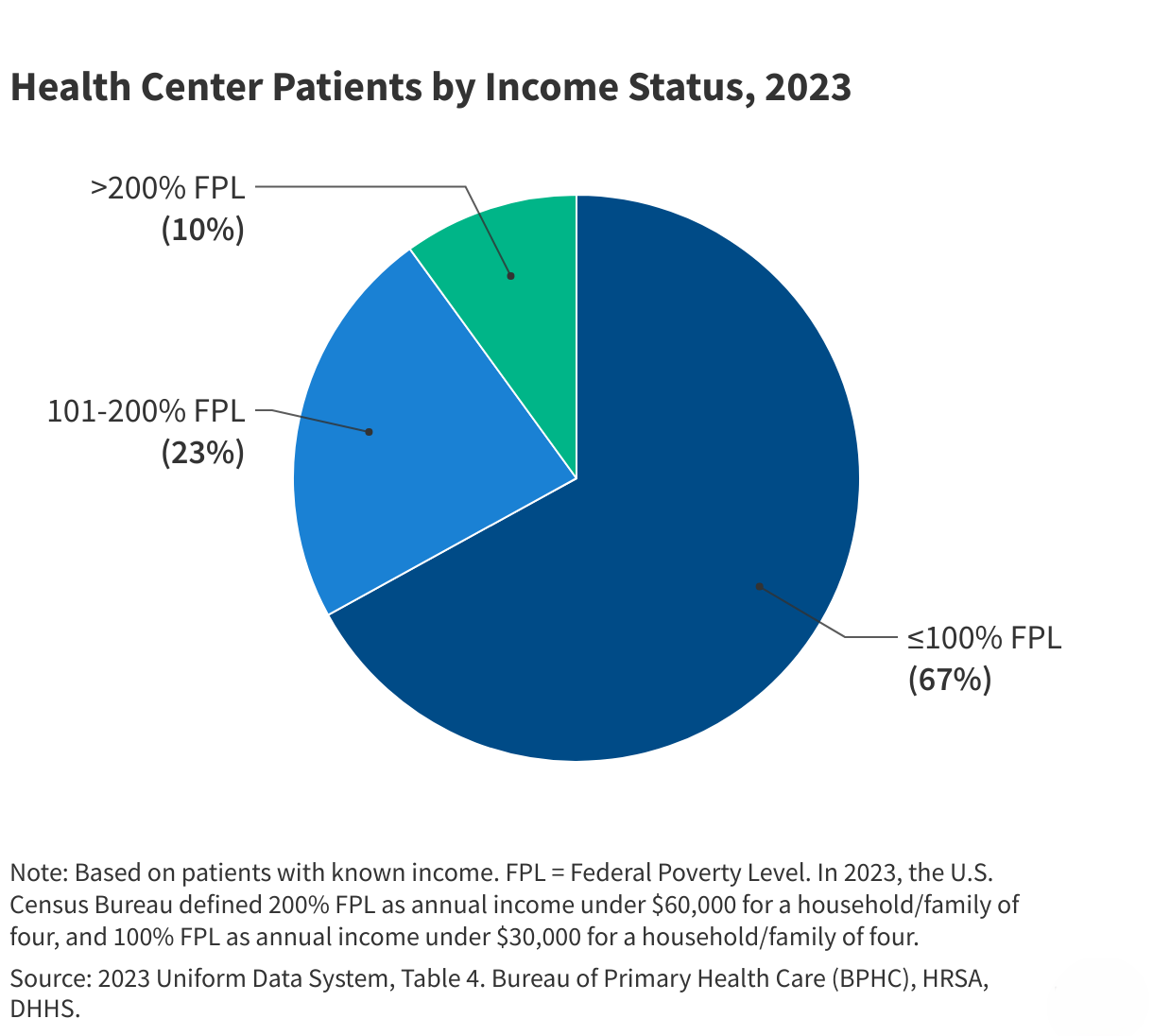

- Health centers disproportionately served low-income people, people of color, and rural residents. In 2023, 90% of patients had incomes that were at or below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL), and 40% were Hispanic patients, 17% were Black patients, and 4% were Asian patients. In addition, over three in ten (31%) patients were rural residents.

- From 2019 to 2023, the share of patients who were uninsured dropped from 23% to 18%, while the share of patients covered by Medicaid increased from 49% to 51%, likely due to the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision, which temporarily halted Medicaid disenrollments from March 2020 through March 2023. The share of patients with private coverage and Medicare also increased modestly.

- Medicaid was the largest revenue source for health centers, accounting for 43% of the $46.7 billion in total health center revenue in 2023, but revenue by payer source varies by state. From 2019-2023, health center revenue increased due to the availability of COVID-19 funding and increased payments from payers. However, net margins after costs fell from 4.5% in 2022 to 1.6% in 2023.

- About 66% of visits were for medical services and 13% were for mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) services. Patients continued to return to in-person care; however, health centers conducted 5 million visits (13%) via telehealth in 2023. Telehealth visits dropped by nearly half from the peak of 28.5 million visits (25%) in 2020 at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Most patients report positive experiences at health centers, with over nine in ten patients reporting that they were treated with respect. However, Black and Hispanic patients were less likely than White patients to report that health center doctors or health professionals explained things in a way that was easy to understand.

Since 2019, health centers have seen a steady rise in the share of their patients who have health coverage and have experienced stable financing; however, potential changes to the Medicaid program could reverse those trends. Changes that would impose new barriers to Medicaid enrollment or alter how the program is financed that may be adopted by the incoming Trump administration or Congress in 2025 would likely lead to an increase in the number of uninsured patients and a loss of Medicaid funding for health centers that could ultimately undermine access to primary care in medically underserved urban and rural areas.

Health Center Patients

In 2023, 1,363 health center organizations served more than 31 million patients at over 15,600 service delivery sites (Figure 1). Roughly six in ten health centers served patients in medically underserved urban areas, while four in ten served rural communities. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of health centers provided care to 25,000 or fewer patients while 3% of health centers served 100,000 or more patients in 2023. Generally, smaller health centers are located in rural areas or focus services on certain neighborhoods or populations, while larger health centers tend to serve more urban areas and operate multiple clinic locations.

Health centers served over 9.1 million children in 2023, an increase of 3.4% from 2022, but still lower than the number of children served prior to the pandemic (Figure 2). The number of child patients ages 0-17 dropped in 2020 likely due to temporary site closures and social distancing guidance at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the number of adult health center patients quickly rebounded after plateauing in 2020, the number of children served by health centers has been slower to recover. There is evidence indicating that utilization of primary and preventive services among children on Medicaid remains below pre-pandemic levels, which may partially explain the drop in pediatric patients at health centers. Although still a small share of the total patient population, the number of adult patients ages 65+ grew by nearly 30% or over 800,000 from 2019-2023.

A majority of health center patients live in low-income households (Figure 3). Reflecting the mission of health centers to serve anyone regardless of ability to pay, nine in ten patients served at health centers had incomes that were at or below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and two-thirds of patients (67%) had incomes at or below the poverty level in 2023 (the poverty level was $30,000 for a family of four in 2023). The share of low-income patients served at health centers is roughly three times that of the U.S. population, in which 28% of individuals lived in households earning under 200% FPL in 2023.

Most health center patients (63%) are people of color, but there are differences between urban and rural health centers in the racial and ethnicity of patients (Figure 4). Across all health centers, Hispanic patients comprised the largest share of patients at 40%, followed by White patients (37%), Black patients (17%), Asian patients (4%), and all other patients (3%). However, the share of health center patients who are patients of color is higher at health centers in urban areas compared to those in rural areas, reflecting differences in the characteristics of people with low-income across the two settings. Patients of color comprise a majority (75%) of patients at urban health centers while White patients represent the majority (61%) of patients at rural health centers.

Health centers served millions of patients who were part of special populations with distinct health needs in 2023 (Figure 5). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), which administers the health center program, provides targeted funding for health centers that serve certain populations identified as underserved by the federal government, including migratory agricultural workers and people experiencing homelessness. In 2023, health centers served 1.4 million patients experiencing homelessness (5% of all patients) and 1 million agricultural workers (3% of all patients). In addition, health centers are also required to report data on other populations with known challenges accessing primary care. For example, three in ten patients (31% or 9.7 million) were rural residents, which is higher than the 20% of the U.S. population living in rural areas, and roughly a quarter of patients (27% or 8.4 million) were best served in a language other than English.

Health Center Patient Coverage and Financing

Fewer than one in five health center patients were uninsured in 2023, continuing the decline in the share of uninsured patients since the start of the pandemic in 2020 (Figure 6). As safety-net providers, health centers serve many patients who are uninsured, enrolled in Medicaid, or who otherwise have difficulty affording care. From 2019 to 2023, the share of uninsured patients dropped from 23% to 18%, while the share of Medicaid patients increased from 49% to 51% and the share of both privately insured and Medicare patients increased. The drop in uninsured patients is likely attributable to the effects of pandemic-era coverage protections, including the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision, which temporarily halted Medicaid disenrollments from March 2020 through March 2023, and enhanced subsidies for Marketplace coverage, enacted in 2021 and extended through 2025. After March 2023, states resumed disenrollments as part of the unwinding of continuous enrollment in Medicaid, and national Medicaid/CHIP enrollment has since declined. Because the unwinding was still ongoing into 2024, the full effect on health center patients’ health coverage will not be clear until data for 2024 and 2025 are available.

In 2023, total health center revenue was $46.7 billion, with Medicaid comprising the largest source of funding (Figure 7). Over two-thirds (68%) of health center revenue came from payments from Medicaid, private insurance, Medicare and self-pay patients, with Medicaid accounting for over 60% of patient care revenue and 43% of total revenue. Federal Section 330 grant funding, which supports health centers’ role as safety net providers, made up 11%. COVID-19 funding, which is set to expire after 2023, accounted for 4% of total revenue. Research suggests that the impact of the expiration of these funds on health center financing may be greater for health centers located in rural areas and in the South, and those with higher shares of sicker, uninsured, and unhoused patients because they generally received higher COVID-19 funding on a per patient basis.

Health center revenue has increased since 2019 in part because of the availability of COVID-19 funding and other supplemental funding during the pandemic. Revenue from payers has also increased in response to the growth in patients. Although Medicaid remains the largest source of funding, Medicaid revenue as a share of total health center revenue decreased from 44% in 2019 to 43% in 2023 (Figure 7). At the same time, payments from private insurance and Medicare both increased as a share of total revenue. In contrast, Federal Section 330 grant funding remained relatively flat, increasing by only $200,000 over the four years and dropping from 16% to 11% of total revenue.

After rising during the pandemic, the national health center net margin fell to 1.6% in 2023 (Figure 8). The increase in health centers’ net margins, which account for both costs and revenue and are reported as a percentage of revenue, was driven primarily by the increase in COVID-related and other supplemental funding during the pandemic. The drop in the net margin in 2023, which is still slightly higher than the margin in 2019, reflected higher costs due to inflation as well as the expiration of COVID-19 funding.

Health Center Services

Health centers provided more than 132 million visits in 2023 (Figure 9). Most visits (66%) were for medical services, though health centers also provided a wide range of other clinical and supportive services, including mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) services (13%), dental services (12%), vision services (1%), and other professional services (3%), which include services such as nutrition counseling, physical therapy, and traditional healing. Enabling or supportive services, which are non-clinical services like case management, transportation, and health education that facilitate access to care, represented 6% of all visits. Health centers are required by federal law to provide primary care and supportive services, and they may offer dental, vision, or other services depending on patient need and organizational capacity.

More patients are returning to in-person care but reliance on telehealth continues. In 2023, health centers provided 17.5 million telehealth visits, which represented 13% of all visits (Figure 10). The number of telehealth visits peaked in 2020 at the start of the coronavirus pandemic when 28.5 million visits (25%) were conducted via telehealth but has declined every year since. Despite the decrease, telehealth still represents an important way for patients to access health center services in 2023, particularly since some patients face geographic and transportation barriers that can make it more difficult for them to attend in-person visits.

Roughly two-thirds (68%) of adult patients have utilized supportive services that are designed to reduce socioeconomic barriers to health care. According to a 2022 survey of health center patients, 65% of adult patients reported ever receiving certain medical-related assistance services and 22% reported ever receiving economic-related assistance through their health center (Figure 11). The medical-related assistance patients reported receiving included help arranging medical appointments outside of the health centers (46%), health education services (24%), free medication (19%), transportation to medical appointments (11%), interpretation during medical visits (8%), and home visits to discuss health needs (3%). Health center patients reported receiving economic-related assistance that included help applying for government benefit programs like Medicaid or nutrition assistance (17%), obtaining food (7%), finding a place to live (4%), obtaining clothing or shoes (3%), and finding employment (2%). Health centers provide economic-related services on-site or through referrals. While the survey identifies some of the most common types of supportive services, the list is not comprehensive.

Health Center Patient Experience

Roughly eight in ten patients reported that they were able to get appointments as soon as they needed at health centers in 2022 (Figure 12). Based on self-reported responses, 60% of health center patients reported they were “always” able to get a check-up or routine care as soon as they needed while 21% said they could “usually” get care as quickly as needed. For patients who needed immediate or urgent care in the past year, three-quarters reported they were “always” (54%) or “usually” (21%) able to the care they needed right away.

Across racial and ethnic groups, most health center patients reported positive experiences interacting with health center doctors and other professionals, but Black and Hispanic patients were less likely than White patients to say doctors or health professionals explained things in a way that was easy to understand (Figure 13). More than nine in ten health center patients (95%) reported that they were usually or always treated with respect by doctors or other professionals at health centers. There were no differences in the share of White, Black, and Hispanic adults who said they were treated with respect. Similarly, 93% of patients said health center staff usually or always listened to them, with no differences between White, Black, and Hispanic patients. These findings for health center patients contrast with other KFF research that shows Hispanic, Black, Asian, and American Indian or Alaska Native adults are more likely than White adults to report unfair treatment by a health care provider due to their race and ethnicity, which can negatively impact their health and well-being. However, Black and Hispanic patients were less likely than White patients to report that health center doctors or health professionals explained things in a way that was easy to understand.