Telehealth can be an important component of facilitating access to care for Medicaid enrollees, particularly the nearly four in ten enrollees with behavioral health needs (mental health conditions and/or substance use disorder (SUD)). During the COVID-19 pandemic, states took advantage of broad authority to expand Medicaid telehealth policies, resulting in high telehealth utilization across populations. In particular, states report that telehealth has helped maintain and expand access to behavioral health care during the pandemic. Indeed, in state fiscal year (FY) 2022, behavioral health, especially mental health, remained a top service category with high telehealth utilization among Medicaid enrollees. Similarly, CMS data indicates that behavioral health services delivered via telehealth increased dramatically during the pandemic; this finding is consistent with other analysis of outpatient visits (including but not limited to Medicaid patients). However, CMS also notes that this increase was not enough to fully offset the decline in the rate of in-person utilization of mental health outpatient services.

Given ongoing provider workforce challenges that present barriers to enrollees’ access to behavioral health care, Medicaid telehealth policy may continue to serve as an important tool for extending the workforce and facilitating improved access to behavioral health care, even beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act requires CMS to issue guidance on Medicaid and telehealth by the end of 2023. The Consolidated Appropriations Act passed in December 2022 authorized additional telehealth provisions, including requirements or funding related to provider directories, crisis services, and virtual peer mental health supports. In the future, Congress could pass additional legislation suggested in a Senate Finance Committee draft on mental health and telehealth.

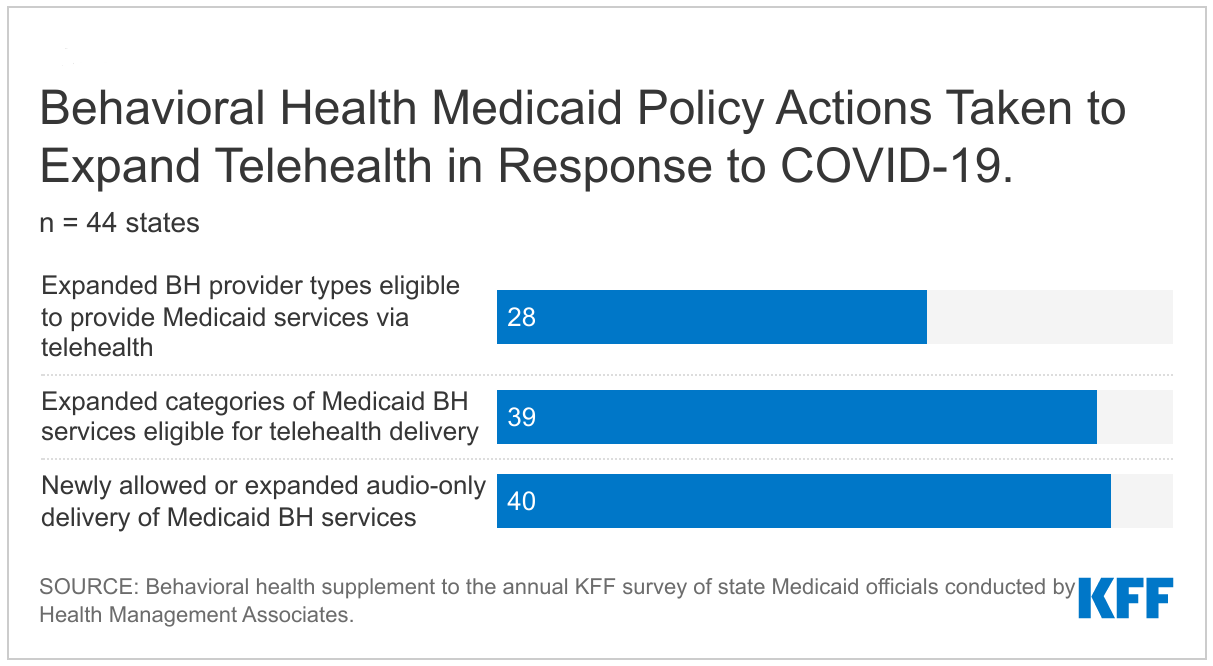

Against this backdrop of state and federal policy activity, KFF surveyed state Medicaid officials about policies and trends related to telehealth delivery of behavioral health services. These questions were part of KFF’s Behavioral Health Survey of state Medicaid programs, fielded as a supplement to the 22nd annual budget survey of Medicaid officials conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA). A total of 44 states (including the District of Columbia) responded to the survey, but response rates varied by question. This issue brief utilizes this survey data to answer three key questions:

- How have states expanded behavioral health telehealth policy in response to COVID-19?

- What trends have states observed in behavioral health telehealth utilization?

- What are key issues to watch looking ahead?

How have states expanded behavioral health telehealth policy in response to COVID-19?

States have broad authority to cover telehealth in Medicaid without federal approval. Prior to the pandemic, the use of telehealth in Medicaid was becoming more common; in particular, most states offered some coverage of behavioral health services delivered via telehealth, and the majority of telehealth utilization was for behavioral health services and prescriptions. However, Medicaid policies regarding allowable services, providers, and originating sites varied widely, and telehealth payment policies were unclear in many states. To increase health care access and limit risk of viral exposure during the pandemic, all 50 states and DC expanded coverage and/or access to telehealth services in Medicaid. We asked states to indicate specific behavioral health Medicaid policy actions taken to expand telehealth in response to COVID-19 and any implemented or planned changes to these policies.

Nearly all responding states took at least one specified Medicaid policy action to expand access to behavioral health care via telehealth (Figure 1). States most commonly reported adding audio-only coverage of behavioral health services, which can help facilitate access to care, especially in rural areas with broadband access challenges and for older populations who may struggle to use audiovisual technology. Also, nearly all states reported expanding behavioral health services allowed to be delivered via telehealth, such as to newly allow telehealth delivery of group therapy or medication-assisted treatment (MAT). Many states noted that virtually all behavioral health services were eligible for telehealth delivery during the pandemic. Finally, most states reported expanding the provider types that may be reimbursed for telehealth delivery of behavioral health services, such as to allow specialists with different licensure requirements (e.g. marriage and family therapists, addiction specialists, and peer specialists). A small number of states noted additional behavioral health Medicaid policy actions beyond those specified; for example, Washington reporting providing technology to enrollees and providers to improve access to behavioral health care during the pandemic.

As of July 2022, states were more likely to allow audio-only coverage of behavioral health services compared to other services. As reported on KFF’s 2022 Medicaid budget survey, nearly all states added or expanded audio-only telehealth coverage in Medicaid in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As of July 1, 2022, a majority of states reported providing audio-only coverage (at least sometimes) across service categories, with mental health and SUD services the most frequently covered categories (Figure 2).

Many states reported permanently adopting some or all of these behavioral health Medicaid telehealth policy expansions. Consistent with responses to KFF’s 2022 Medicaid budget survey, many states reported permanent (i.e. non-emergency) adoption of telehealth policy expansions that were initially enacted during the pandemic on a temporary basis. In particular, states frequently noted that all or most expansions of behavioral health providers and/or services allowed for telehealth would be maintained after the public health emergency. However, some states also reported limiting or adding guardrails to pandemic-era behavioral health telehealth flexibilities. Most commonly, states reported that they would limit coverage of audio-only telehealth for behavioral health services, consistent with concerns about the quality of audio-only telehealth reported on the budget survey.

What trends have states observed in behavioral health telehealth utilization?

To better understand the impacts of behavioral health telehealth policy changes during the pandemic, we asked states to indicate whether they monitor behavioral health telehealth utilization in Medicaid and, if so, to report utilization trends by geography, demographics, and other factors.

Nearly all responding states monitored utilization of behavioral health services delivered via telehealth in FY 2022 or plan to begin doing so in FY 2023 (Figure 3). Telehealth utilization data can help states assess the impacts of expanded telehealth policy. These assessments may inform future quality and other analyses. Some states that already monitor behavioral health telehealth utilization reported future plans to increase this monitoring and/or to stratify utilization data by additional demographic or other factors.

Many states reported high utilization of telehealth for behavioral health care across all or most Medicaid populations, though some states noted utilization trends among certain subgroups of Medicaid enrollees, such as:

- Geographic trends, with states most commonly reporting particularly high behavioral health telehealth utilization in rural areas compared to urban areas. Telehealth could be an important tool for facilitating access to behavioral health care for Medicaid enrollees in rural areas with fewer provider and hospital resources.

- Demographic trends, which were most commonly captured by race/ethnicity and age. These trends generally mirror overall data indicating that behavioral health conditions are most prevalent among young adults and White people. In particular, some states reported that younger enrollees (including children and non-elderly adults) were most likely to utilize telehealth for behavioral health care. Several states reported higher telehealth utilization among White individuals compared to people of color. A small number of states reported that female enrollees were more likely to utilize telehealth compared to male enrollees.

- Temporal trends, with states frequently reporting that behavioral health telehealth utilization has declined from its peak earlier in the pandemic, but remains high compared to the pre-pandemic period. Future policy changes, such as to further expand or to limit telehealth flexibilities, may impact ongoing utilization. For example, South Carolina reported anticipating an increase in behavioral health telehealth utilization among children in FY 2023 as part of an initiative to increase access for school-based mental health services.

The trends summarized above are generally consistent with overall Medicaid telehealth utilization trends reported on KFF’s 2022 budget survey. Additionally, several states reported that telehealth utilization was higher for mental health services compared to SUD services (this trend likely reflects the higher prevalence of mental health conditions compared to SUD conditions among Medicaid enrollees). A few states reported that demographic utilization trends varied by service or provider type. For example, New York indicated that female enrollees were more likely than male enrollees to receive psychological and psychiatric services via telehealth, but that male enrollees were more likely to receive SUD services via telehealth. Colorado reported that utilization trends by race/ethnicity were related to provider type, as community mental health centers are likelier to use telehealth and are also likelier to serve more racially/ethnically diverse populations.

What are key issues to watch looking ahead?

Key issues that may influence states’ future behavioral health Medicaid telehealth policy decisions include analysis of utilization and other data as well as federal guidance:

- Data and quality: As states continue and expand their monitoring of behavioral health telehealth utilization, the results of these analyses may provide information that can inform policy decisions. Also, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has recommended that CMS collect information to assess the impact of telehealth on quality of care for Medicaid enrollees, and most states report questions and/or concerns about the quality of services delivered via telehealth that may be addressed through ongoing data analysis.

- Federal guidance and legislation: States also report watching for further guidance from the federal government related to Medicaid telehealth policies. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Actsigned into law in June 2022 directs CMS to issue guidance to states on options and best practices for expanding access to telehealth in Medicaid, including strategies for evaluating the impact of telehealth on quality and outcomes. CMS must issue this guidance by the end of 2023. The Consolidated Appropriations Act passed in December 2022 authorized additional telehealth provisions, such as requirements for Medicaid provider directories to include information on telehealth coverage and for CMS to issue guidance on how states can use telehealth to deliver crisis response services. The Act also authorized grants for nonprofits to expand and improve virtual peer mental health support services, as well as other non-Medicaid telehealth provisions (such as telehealth policies for veterans and for Medicare enrollees). Several of these federal Medicaid telehealth policies passed in 2022 follow from a Senate Finance Committee discussion draft on ensuring access to telehealth, released by the Committee in May 2022 as part of a series of drafts associated with its mental health care initiative. Looking ahead, Congress could take up additional policies suggested in the draft, such as to require public aware

As states emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic and grapple with behavioral health workforce shortages, the continuation of expanded telehealth policy—informed by data analysis and federal guidance—may be an important component of maintaining access to behavioral health care for enrollees.

This work was supported in part by Well Being Trust. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

This brief draws on work done under contract with Health Management Associates (HMA) consultants Angela Bergefurd, Gina Eckart, Kathleen Gifford, Roxanne Kennedy, Gina Lasky, and Lauren Niles.