With uptake of COVID-19 vaccines and boosters leveling off and the U.S. currently in the midst of another Omicron wave, ensuring equitable and rapid distribution of COVID-19 treatments will be important for mitigating the uneven impacts of the pandemic. COVID-19 has disproportionately affected certain underserved and high-risk populations, including people of color and those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged. Because many of these groups remain at increased risk of exposure, given that they are less likely to work in jobs that can be done remotely and due to other structural factors, access to treatments (in addition to vaccines) is particularly important. The Biden Administration has identified increasing access to COVID-19 treatments as a priority, but there has been wide variation in access across states and local jurisdictions.

To date, data on who has received COVID-19 treatments remains very limited, hindering the ability to assess whether access to them has been equitable. To provide better insight into access to COVID-19 treatments, we analyzed data from the HHS Office of the Assistance Secretary for Preparedness and Response on public locations that have received shipments of federally-procured oral antiviral COVID-19 treatments. We examined availability treatments by county and certain county characteristics, including metro vs. non-metro status, poverty rate, and majority Black, Hispanic, or American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN), the groups who have experienced the largest disparities in COVID-19 health outcomes. The analysis is limited to oral antiviral COVID-19 treatments that can be administered at home.

In sum, the findings show that:

- COVID-19 oral antiviral treatments are available through facilities across the country and nearly all people live in a county with availability regardless of whether they live in a metro or non-metro area, their income, or their race/ethnicity.

- However, the small number of counties with the highest poverty rates and those that are majority Black, Hispanic, and AIAN are less likely to have a facility with COVID-19 treatments available and have fewer facilities available compared to their counterpart counties. Findings are more mixed for treatment courses. Non-metro and majority Hispanic and AIAN counties also have fewer courses available than their counterpart counties, while high poverty and majority Black counties having slightly larger numbers of courses available.

In sum, while nearly all people live in a county with a facility with COVID-19 treatments available, disparities in access persist among the potentially highest risk and highest need counties. Non-metro counties and majority Hispanic and AIAN counties, which have fewer facilities and courses available have more limited access to treatments overall. High poverty and majority Black counties, which have fewer facilities but more courses available relative to their population size, may not have disparities in terms of number of treatments available, but may still have more limited access, as individuals could have to travel a farther distance to obtain them. Given that there have been no recent shortages in treatment courses, proximity to a facility may be a more relevant measure of access at this time.

While this analysis provides some insight into the availability of facilities and treatments, getting them also depends on having knowledge about treatments, access to medical advice, and the time and resources to obtain them. However, to date, no federal data is available on who is receiving treatments. Going forward, continued steps to ensure equity in access to COVID-19 treatments will be important, as will increasing data availability to understand who has received COVID-19 treatments.

Background

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued emergency use authorization for two home oral antiviral COVID-19 treatments. These treatments – Paxlovid and Lagevrio – are available for people who test positive for COVID-19 and are at high risk of developing serious illness. They must be taken within the first five days after COVID-19 symptoms appear and each require a prescription from a health care provider. Both have been shown to significantly reduce hospitalization and death from COVID-19. The federal government has purchased supplies of both treatments for distribution to sites throughout the country and to be provided for free to those who are eligible.

The Biden Administration launched a nationwide Test to Treat initiative in March 2022 to expand access to oral antiviral COVID-19 treatments. The Test-to-Treat initiative builds on prior distribution of oral antivirals, which began in December 2021, to states, Tribes, territories, and community health centers, which in turn distribute these treatments to health care providers, pharmacies, and other locations. The goal of this program is to enable people to get tested and, if they are positive and treatments are appropriate for them, receive a prescription from a health care provider and have their prescription filled all at one location. These Test-to-Treat sites are available at locations nationwide, including clinics, federally-funded health centers, long-term care facilities, and community-based sites. In May 2022, the Administration expanded the initiative to include new federally-supported Test-to-Treat locations that focus on reaching hard-hit and high-risk communities and helping to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 treatments. The Administration indicates that 40% of pharmacy sites with oral antivirals available are located in communities with the highest levels of social vulnerability.

Key Findings

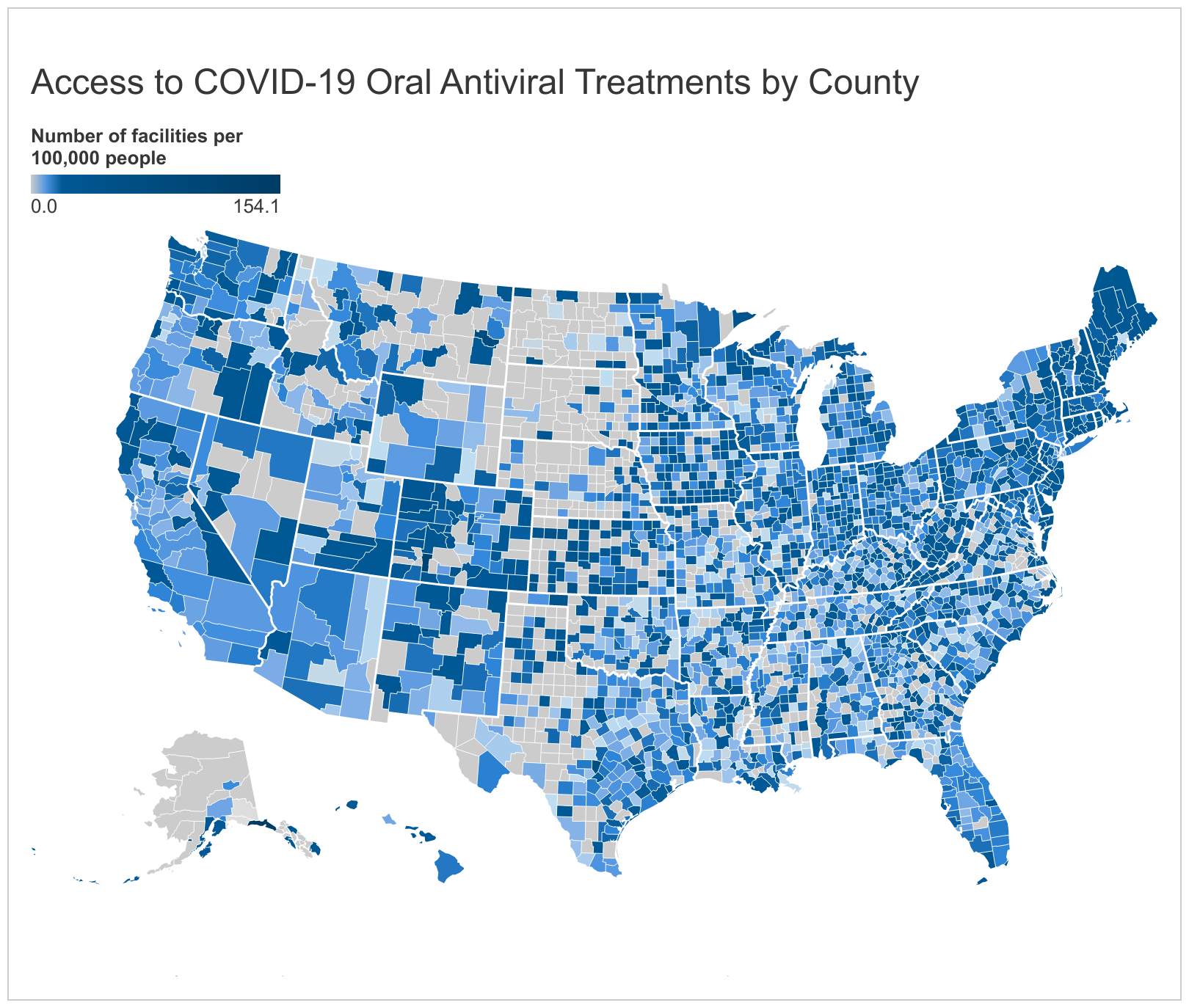

Nearly all people (98%) live in a county with at least one facility that has COVID-19 oral antiviral treatments available. As of June 7, there were 2.6 million courses of oral antiviral treatments available in 37,100 facilities across the U.S. Nearly 8 in 10 (79%) of counties have a facility with COVID-19 oral antiviral treatments available, while one in five (21% or 665) counties do not. Even with these gaps in some counties, nearly all people in the U.S. (98%) live in a county with a facility available regardless of whether they live in metro or non-metro area, their income, or their race/ethnicity.

The average number of facilities and treatment courses available varies across counties. On average, there are 10.2 facilities and 668 treatment courses available per 100,000 people per county. However, the number of facilities per 100,000 ranges greatly, from 0 to 154 across counties. Similarly, the number of courses per 100,000 ranges from 0 to 22,644 across counties.

On average, access to COVID-19 oral antivirals is largely comparable between metro and non-metro counties, although non-metro counties are more likely to not have a facility with treatments available. Nationwide, there are 1,167 metro counties and 1,976 non-metro counties. The majority (86%) of the population lives in metro counties, while 14% lives in non-metro counties. Non-metro counties are more likely than metro counties to not have a facility with oral antiviral treatments available (28% vs. 9%), and people living in a non-metro county are less likely to have a facility with treatment available (92% vs. 100%). However, the average number of facilities per 100,000 people was similar for metro (10.7) and non-metro (9.9) counties, reflecting the lower population density in non-metro counties. Metro counties did have more courses available compared to non-metro counties (737 vs. 629 per 100,000 people).

Although nearly all people (98%) with incomes below poverty live in a county that has a facility with COVID-19 treatments available, high-poverty counties have fewer facilities available than areas with lower rates of poverty. While most counties have low or moderate poverty rates (defined as less than 10% and between 10% and 30%, respectively), a small number (87) counties have a high poverty rate of 30% or more. Four in ten (40%) high poverty counties did not have a facility with oral antiviral COVID-19 treatments available compared to 26% of low poverty counties and 19% of moderate poverty counties. Moreover, high poverty counties had fewer facilities compared to low and moderate poverty counties (7.7 vs. 10.4 and 10.2 per 100,000 people, respectively). However, high poverty counties have slightly more treatment courses available compared to low and moderate poverty counties (692 vs. 601 and 686 per 100,000 people, respectively).

Majority Black, Hispanic, and American Indian Alaska Native (AIAN) population counties have more limited access to facilities with oral antiviral COVID-19 treatments than non-majority Black, Hispanic, and AIAN counties. (There were no majority Asian counties, so similar analysis was not conducted for this group.)

- Overall, there are 96 counties where Black people make up 50% or more of the population. These counties are home to nearly 10% of the total Black population. While nearly all Black people (99%) live in a county that has a facility with COVID-19 treatments available, these majority Black counties have more limited access compared to non-majority Black counties. Roughly one in three (31%) majority Black counties did not have a facility with oral antiviral COVID-19 treatments available compared to 21% of counties where Black people make up less than half of the population. Moreover, there were 8.6 facilities per 100,000 people in majority Black counties compared to 10.3 facilities per 100,000 people in non-majority Black counties. However, majority Black counties had a somewhat larger number of courses available on average compared to non-majority Black counties (705 vs. 667 per 100,000 people).

- Hispanic people account for at least 50% of the population in 102 counties that are home to nearly 20% of the total Hispanic population. Nearly all Hispanic people (99%) live in a county with a facility with COVID-19 treatments available, but majority Hispanic counties have fewer facilities available than non-majority Hispanic counties. One-third (33%) of majority Hispanic population counties did not have a facility with COVID-19 treatments available compared to about one in five (21%) of non-majority Hispanic counties. On average, there were 7.3 facilities per 100,000 people in majority Hispanic counties compared to 10.3 facilities per 100,000 people in non-majority Hispanic counties. Majority Hispanic counties also had fewer courses available than non-majority Hispanic counties (503 vs. 674 per 100,000 people).

- In 28 counties, AIAN people make up 50% or more of the population, and these areas are home to 11% of the total AIAN population. Overall, just over nine in ten (91%) of AIAN people live in a county with a facility available. However, three-quarters (75%) of AIAN majority population counties did not have a facility with COVID-19 treatments available compared to roughly one-quarter (21%) of non-majority AIAN counties. Moreover, majority AIAN counties had a lower average number of facilities available than non-majority AIAN counties (4.2 vs. 10.3 per 100,000 people) and a lower average number of courses available (185 vs. 673 per 100,000 people).

Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected the health and financial security of people of color due to underlying disparities that place people of color at increased risk for exposure and illness, and ensuring equity in access to COVID-19 treatments (as well as vaccines) is important for mitigating disparities and preventing against further widening of disparities going forward.

This analysis shows that while treatments are available at facilities across the country and nearly all people live in a county with such a facility, regardless of their income, race/ethnicity, or whether they live in a metro or non-metro area, some disparities in access persist among the potentially highest risk and highest need counties. Non-metro counties and majority Hispanic and AIAN counties, which have fewer facilities and courses available have more limited access to treatments overall. High poverty and majority Black counties, which have fewer facilities but more courses available relative to their population size, may not have disparities in terms of number of treatments available, but may still have more limited access, as individuals could have to travel a farther distance to obtain them. Given that there have been no recent shortages in treatment courses, proximity to a facility may be a more relevant measure of access at this time.

While the counties facing disparities account for a small share of counties overall, they represent areas that have the highest shares of residents who have borne the heaviest burdens of the pandemic. These high burden counties represent a narrower set of counties than those that measure high on the overall social vulnerability index, an index developed by the federal government to identify communities that will most likely need support in response to hazardous events, which the Administration is using to guide equitable distribution. Our findings suggest that distribution based on the social vulnerability index alone may leave some areas with high concentrations of residents at increased risk facing gaps in access, and as such, additional equity lenses may be helpful for promoting access.

Importantly, while this analysis provides some insight into the availability of COVID-19 oral antiviral treatments, getting them also depends on having knowledge about treatments, access to medical advice, and the time and resources to obtain them. As such, even if there is broad geographic availability of treatments, there may still be disparities in who is able to obtain them. Going forward, continued steps to ensure equity in access to COVID-19 treatments will be important, as will increasing data available to understand who has received them.

Methods

For this data note, KFF researchers analyzed data at the county level and drawing from multiple sources:

Our main outcome of interest, facilities with oral antiviral COVID-19 treatments available, was collected from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) COVID-19 Public Therapeutic Locator Data as of June 7, 2022 The HHS data includes locations that have received an order of Evusheld, Paxlovid, Renal Paxlovid, Lagevrio (molnupiravir), or bebtelovimab in the last two months and/or have reported availability of these therapeutics within the last two weeks. The analysis is limited to locations in the 50 states and D.C. (excludes territories) that reported inventory in the past two weeks and have a current supply of oral antivirals (Paxlovid, Renal Paxlovid, or Lagevrio). Locations that did not report inventory within the prior two weeks and whose status was unknown were not included in the analysis. These locations may have treatments available but are not counted as an active location in this analysis.

Metro and non-metro classifications are based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Counties with codes 1 through 3 are classified as “metro” and 4 through 9 are classified as “non-metro.” The rural-urban continuum codes distinguish metropolitan counties by the population size of their metro area and nonmetropolitan counties by degree of urbanization and adjacency to a metro area. Data to categorize counties by racial composition of residents is based on the Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Estimates by county. Specifically, we calculate the share of the county population that is majority (50% or more) Hispanic, non-Hispanic American Indian Alaska Native, and non-Hispanic Black. Non-Hispanic Asian people were not included in this analysis, as no county had a majority non-Hispanic Asian population according to 2019 ACS data. Data to categorize counties by poverty level is also based on the Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates by county. We used the 30% threshold to define “high poverty” since research has shown that the negative effects of neighborhood poverty are most prominent when a neighborhood has between 20% and 40% poverty and 30% is commonly used in existing literature measuring high poverty neighborhoods.

Appendix

| Key Characteristics | Number of Counties | Percent of Counties without a Facility with Oral Antiviral COVID-19 Treatments Available | Average Number of Facilities with Oral Antiviral COVID-19 Treatments Available per 100,000 by County | Average Number of Oral Antiviral COVID-19 Treatment Courses Available per 100,000 by County | |

| Geography | |||||

| Metro | 1,167 | 9% | 10.7 | 737 | |

| Non-Metro | 1,976 | 28% | 9.9 | 629 | |

| Income | |||||

| Low Poverty (<10% below poverty) | 654 | 26% | 10.4 | 601 | |

| Moderate Poverty (10-30% below poverty) | 2,401 | 19% | 10.2 | 686 | |

| High Poverty (30%+below poverty) | 87 | 40% | 7.7 | 692 | |

| Racial Composition | |||||

| Non-Majority Black (<50%) | 3,046 | 21% | 10.3 | 667 | |

| Majority Black (50%+) | 96 | 31% | 8.6 | 705 | |

| Non-Majority Hispanic (<50%) | 3,040 | 21% | 10.3 | 674 | |

| Majority Hispanic (50%+) | 102 | 33% | 7.3 | 503 | |

| Non-Majority AIAN (<50%) | 3,114 | 21% | 10.3 | 673 | |

| Majority AIAN (50%+) | 28 | 75% | 4.2 | 185 | |

| NOTES: Values (excluding the number of counties column) have been rounded to the nearest whole number. For Geography, counties with USDA Rural-Urban Continuum Codes between 1 and 3 are classified as “metro” and counties with codes 4 through 9 are classified as “non-metro”. Only the 50 states and D.C. were included in this analysis (territories were excluded). Further, only therapeutics providers that have reported on their inventory status in the past two weeks as having a current available supply of oral antivirals (Paxlovid, Renal Paxlovid, or Lagevrio) were included. | |||||

| SOURCE: Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey Estimates (used for both Poverty and Racial Composition analyses); U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) COVID-19 Public Therapeutic Locator Data, as of June 7, 2022. | |||||

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.