The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), enacted at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, requires states to provide continuous enrollment to Medicaid enrollees until the end of the month in which the public health emergency (PHE) ends in order to receive enhanced federal funding. During this time, states generally cannot disenroll people from Medicaid, which has prevented coverage loss and churn (moving off and then back on to coverage) among enrollees during pandemic. The PHE is currently in effect through mid-April 2022 and the Biden administration has said it will give states 60 days’ notice before the PHE ends. Since that notice was not issued in February 2022, it is expected the PHE will be extended again, although there is uncertainty over how long the extension will last.

Once states resume redeterminations and disenrollments at the end of the PHE, Medicaid enrollees who moved within a state during the pandemic but are still eligible for coverage are at increased risk of being disenrolled if their contact information is out of date. Many state Medicaid programs are heavily reliant on the mail for communicating with enrollees about renewals and redeterminations, including requests for information and documentation. States can disenroll individuals who fail to respond to these requests. We analyzed federal survey data for 2020 and found:

- Roughly 1 in 10 Medicaid enrollees (9%) moved in-state in 2020. A much smaller share, just 1%, moved to a different state in the U.S. Individuals that move within the same state may continue to be eligible for Medicaid, while a move out of state would make them no longer eligible for Medicaid coverage in their previous state. Shares of Medicaid enrollees moving within a state has trended downward in recent years, but trends could have changed in 2021, as more people became vaccinated against COVID-19 and the national eviction moratorium was lifted in August 2021.

- Among those covered by Medicaid, young adults and single-parent families with children were more likely to move within a state than other groups. Among Medicaid enrollees that moved within the same state in 2020, half (50%) moved for housing-related reasons and 28% moved for family-related reasons.

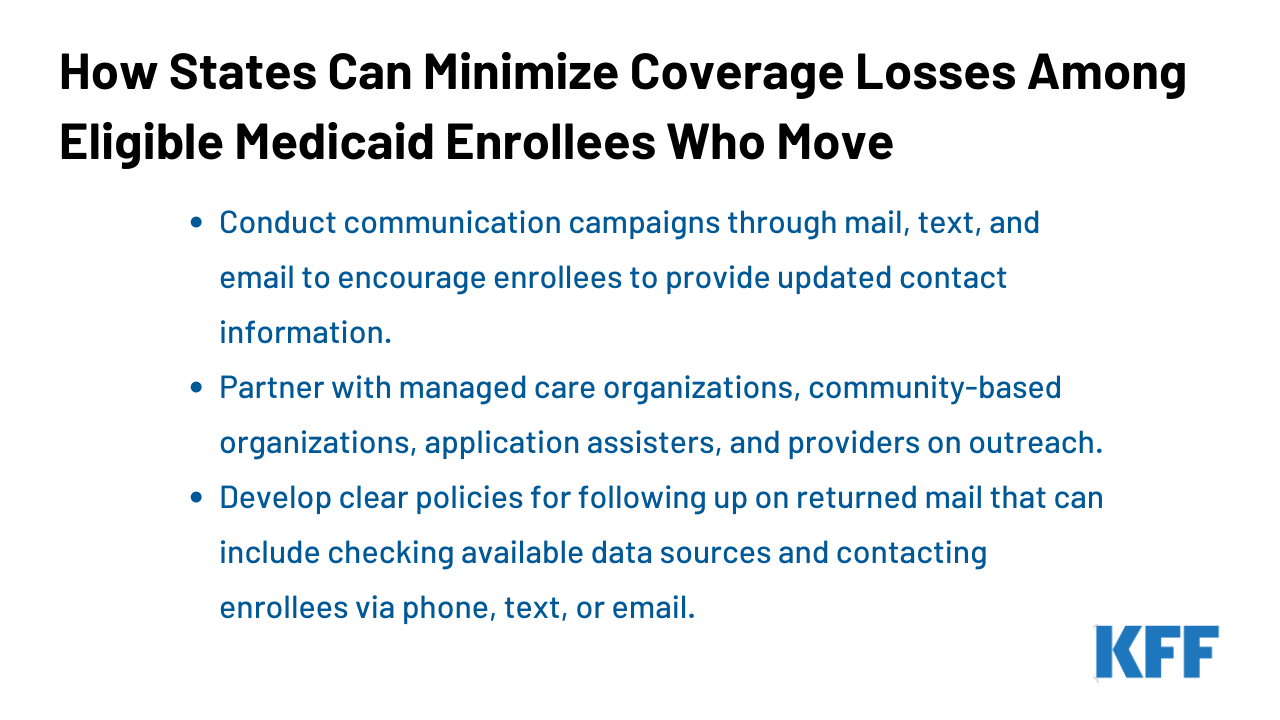

States can take a number of actions to update enrollees’ addresses and other contact information to minimize coverage gaps and losses for eligible individuals after the end of the PHE, particularly for individuals who may have moved within a state. These actions include conducting direct outreach to enrollees, partnering with managed care organizations and other stakeholders in outreach efforts, developing clear policies for returned mail, and checking available data sources for more up-to-date contact information. A recent survey of states found that most states (46) were taking proactive steps such as these to update contact information, although fewer (35) are following up on returned mail. Careful monitoring and oversight of state progress during the unwinding period could provide information to prevent erroneous terminations of coverage.

Introduction

To understand who may be at increased risk of losing Medicaid coverage because of out-of-date contact information, this brief analyzes data from the Current Population Survey’s (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) from March 2021 to examine the share of Medicaid enrollees who moved within a state (and therefore are more likely to remain eligible for Medicaid in the same state) in 2020 and the demographic characteristics of those individuals. It also examines trends in residential mobility over time and discusses strategies states can adopt to minimize coverage losses among these individuals.

The data used in our analysis reflect mobility patterns during 2020 and were collected before important events, such as when the COVID-19 vaccine became widely available to all adults and the end of the national eviction moratorium, that may have affected the number of people who moved more recently. Additionally, our analysis focuses on non-elderly Medicaid enrollees (because enrollees ages 65 and older likely have Medicare as their primary source of coverage) and so we refer to non-elderly Medicaid enrollees simply as “enrollees” for the remainder of this brief. See the Methods box at the end of this brief for more details about the analysis and limitations.

What do we know about Medicaid enrollees who moved in-state in 2020?

Roughly 1 in 10 Medicaid enrollees (9%) moved in-state in 2020. A much smaller share, just 1%, moved to a different state in the U.S., which would make them no longer eligible for Medicaid coverage in their previous state. The share of enrollees moving within the same state was slightly higher compared to people who are not enrolled in Medicaid (8%), although the share was not significantly different for non-enrollees who moved to a different state in 2020 (2%). These estimates are based on CPS ASEC data, which asks survey respondents whether they lived in the same house one year ago. One limitation of this approach is that the CPS ASEC data do not identify people who have moved multiple times over the course of the year, reflecting more severe housing instability that is more common among low-income populations. Additionally, these data do not identify temporary (or seasonal) moves during the year, such as moving in with family or friends, which became more common in 2020 and early 2021 in response to the pandemic.

Among those covered by Medicaid, young adults and single-parent families with children were more likely to move within a state than other groups (Figure 1). In 2020, approximately 11% of young adults (ages 19-34) with Medicaid coverage moved in-state compared to 8% of children and 7% of adults ages 35-64 with Medicaid. Among the different family types analyzed, enrollees who live in single-parent families were the most likely to move in 2020 (12%), while enrollees living in multi-generational families were among the least likely to move (6%). When we compared residential mobility by race/ethnicity, a smaller share of Hispanic people enrolled in Medicaid moved within state in 2020 (7%) compared to White people (9%), while the shares of Black people (9%) and people of other races (9%) who moved were not different compared to White people.

Among enrollees that moved within the same state in 2020, half (50%) moved for housing-related reasons and 28% moved for family-related reasons (Figure 2). Housing-related reasons include wanting a better home and/or neighborhood, wanting cheaper housing, foreclosure or eviction, and other unspecified housing-related reasons. Family-related reasons include establishing one’s own household, changes in marital status, and other unspecified family reasons. Generally, Medicaid enrollees were more likely to move in-state for family-related reasons compared to people who were not enrolled in Medicaid (28% vs. 24%) and were less likely to move in-state for job-related reasons compared to people who were not enrolled (9% vs. 12%). Medicaid enrollees and non-enrollees both moved within the same state for housing-related or other reasons at about the same rate. When compared to the reason people moved in 2018 (the most recent measurement year before the pandemic), Medicaid enrollees’ reasons for moving have stayed relatively steady despite economic disruptions in 2020 related to the pandemic.

The share of Medicaid enrollees moving within the same state has declined slightly in recent years, from 15% in 2014 to 9% in 2020, although that trend could change in 2021 and 2022 (Figure 3). Declining shares of Medicaid enrollees moving within the same state since 2014 mirrors national trends of fewer people moving over time. However, the share of Medicaid enrollees moving has decreased faster compared to non-enrollees in recent years. While the pandemic has raised concerns about economic disruptions and housing instability among low-income populations, the data for 2020 indicate that residential mobility among both Medicaid enrollees and non-enrollees largely followed pre-pandemic trends. However, these trends could have changed in 2021, as more people became vaccinated against COVID-19 and the national eviction moratorium was lifted in August 2021.

How can states minimize coverage losses among eligible enrollees who move?

With the continuous enrollment requirement in place during the PHE and the prohibition on disenrolling individuals from Medicaid, states may not be communicating regularly with enrollees and, as a result, may have outdated contact information for those who have moved within the state during the past two years. When the PHE ends and states resume routine redeterminations and disenrollments, some enrollees may be at risk of losing coverage simply because they do not receive notices or renewal information. As states prepare to resume normal operations, they can take a number of actions to update enrollee addresses and other contact information to minimize coverage gaps and losses for eligible individuals. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed a broad set of policy and operational strategies states can adopt to maintain continuous coverage for eligible individuals, including specific strategies for updating contact information and reducing returned mail:

Conduct communication campaigns through mail, text, and email to encourage enrollees to provide updated contact information. States can send periodic notices during the PHE to remind enrollees to update their contact information. To the extent states have alternative contact information, they can also reach out through automated phone calls, text messages and emails. And, to ensure that enrollees are reminded when they proactively reach out to the Medicaid or other social services agencies, states can update call center scripts to request updated contact information at the beginning of the call and can add alerts to Medicaid, CHIP, and social services websites.

Partner with managed care organizations (MCOs), community-based organizations, application assisters, and providers in outreach efforts. To expand the reach of outreach efforts, states can work with MCOs, community partners, and providers to reinforce messages and remind enrollees to provide updated information. Enrollees are used to receiving communication from MCOs and may be more likely to respond to reminders from them. Navigators and certified application assisters can also be effective partners because they regularly update contact information during interactions with clients. States can opt to accept updated information from these entities, or in the case of MCOs require that they share this information but should develop policies for verifying updated information with enrollees.

Develop clear policies for following up on returned mail that can include checking available data sources and contacting enrollees via phone, text, or email. When mail is returned and no forwarding address is provided, states are encouraged to check available data sources, including the United States Postal Service (USPS) National Change of Address Database, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) or other programs, and/or contact information from MCOs. They can also contact enrollees via phone, text, or email to obtain updated mailing addresses.

To prepare for the end of the PHE and continuous enrollment requirement, most states (46) are taking proactive steps to update enrollee addresses, although fewer (35) are following up on returned mail as of January 2022. Actions to update addresses include conducting outreach to enrollees, checking other programs for updated addresses, and working with managed care plans and providers to update address information. States that follow up on returned mail are most likely to call or email enrollees using information on file when they received returned mail from a notice sent to an enrollee.

Looking Ahead

As states resume redeterminations and disenrollments at the end of the PHE, evidence suggests that it is unlikely that large proportions of enrollees would be no longer eligible for Medicaid because they moved out of state. When asked to predict the primary reasons people will lose coverage after the continuous enrollment requirement is lifted, few states (3) identified moving as a key driver of disenrollments, and all cited other reasons, including increased income or other changes in circumstances, in addition to moving. While the number of Medicaid enrollees moving within the same state did not increase during the first year of the pandemic, the 9% of Medicaid who moved in-state in 2020 still amounts to a significant number of enrollees whose contact information is more likely to be out of date and who are at increased risk of losing coverage as states unwind the continuous enrollment requirement. It is also possible that, as the pandemic continued into 2021 and 2022, the cumulative number of Medicaid enrollees who moved has increased as well. States with relatively large numbers of disenrollments due to returned mail may indicate erroneous terminations, as returned mail alone does not necessarily indicate a change in economic circumstances that affects eligibility, especially when relatively few enrollees move out of state (approximately 1% of enrollees in 2020). Careful monitoring and oversight of state progress during the unwinding period could provide information to prevent erroneous terminations of coverage.

| We analyzed data from Current Population Survey’s (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) from March 2021, 2019, 2017, and 2015. These data provide information on who moved during the previous year (2020, 2018, 2016, and 2014, respectively). Our analysis focuses on people who had Medicaid coverage at some point during the year and who moved within the same state (moving out of state would mean that the enrollee no longer qualifies for Medicaid coverage in the previous state). We exclude enrollees ages 65 and older since nearly all would qualify for Medicare and are less likely to lose their primary source of coverage. Children under age 1 are also excluded because the CPS ASEC questions on moving as of March of the previous year are not applicable to respondents under age 1. Our analysis also focuses on individuals who moved within the US. While our analysis includes a small number of people who have moved from outside the U.S. (i.e., from a US territory or a foreign country), we do not include these individuals in our counts of people who moved in-state or to a different state. For the March 2021 CPS data (and not for previous years), we analyzed differences in selected demographic groups, including age group, family type, and race/ethnicity. We also analyzed the share of people moving within state by sex, urban/rural (using metropolitan statistical areas as a proxy), and foreign born, but we did not find significant differences between these groups and so are not shown in Figure 2. All differences reported in this brief are measures at the p < 0.05 level.

The analysis focuses on individuals and uses person weights, which is important for interpreting our findings on demographic groups. For example, although children will typically move with adults, the difference between child enrollees and older enrollees reflects situations where adults do not live with children or, in some cases, children (especially those aged 18) who do not live with adults. In other households, the children may be enrolled in Medicaid but their parents are not, or there could be more children enrolled in Medicaid than adults (or vice versa). In analyzing family type, we consider the type of family for each individual. For example, while we excluded enrollees ages 65 and older from our analysis, child enrollees who live with their parents and grandparents are considered to live in multi-generational households. We conducted a robustness check of our findings by comparing the share of people moving in-state as identified in the CPS ASEC versus the American Community Survey (ACS). We compared findings for Medicaid enrollees and non-enrollees ages 1-64, using data collected in the March 2019 CPS ASEC sample and the 2019 ACS sample. Generally, the percent of people moving in-state over the past year were slightly lower in the March 2019 CPS ASEC sample (11% of enrollees and 8% of non-enrollees) compared to the 2019 ACS sample (13% of non-enrollees and 11% of non-enrollees). We would expect some differences due to different and data collection methods and timing between CPS and ACS, and so the difference of 2 or 3 percentage points seemed reasonably small. Our findings have important limitations. First, the CPS ASEC sample does not tell us when a person moved. So, we do not know whether the person was enrolled in Medicaid before, during, or after the move. Additionally, we do not know how many times a person moved and, depending upon timing, temporary moves may not be captured. Second, the latest CPS data used here only provide data for 2020, but the economic impacts of the pandemic have lasted much longer, including when the federal government lifted the national eviction moratorium in August 2021. |

I must admit that your post is really interesting. I have spent a lot of my spare time reading your content. Thank you a lot!

Hi, I log on to your new stuff like every week. Your humoristic style is witty, keep it up

Battle ropes could be a challenging exercise but

there are lots of modifications that may be made to make it a great train for newbies.

Battle ropes make for efficient cardio and muscle-building exercise and would

be an excellent option for beginners because

of that. As Quickly As they get into the bottom squat they’ll then jump up right into a bounce squat

while persevering with to maneuver the battle ropes. The alternating wave, also referred to as the unilateral waves

train, is finished by swinging every rope one at a time.

With the single-arm cable extension, you probably can customize your range of movement to match your

particular person needs and limitations. This means

you can goal the triceps effectively no matter your level of flexibility or when you have any injuries.

In Contrast to free weights, cable shoulder presses offer a

a lot smoother motion that significantly reduces stress on the shoulder joints.

For greatest outcomes, attempt to carry out different rope move workouts

as a whole exercise on their own.

And that’s why I’m kicking things off with a breakdown of

the shoulder muscle tissue earlier than moving into

the wider vary of exercises. It’s just as essential (more so) to know how the muscle

fibers work as it’s to learn effective shoulder workouts for them.

A shoulder exercise with cables can even handle muscle imbalances and scale back the risk of shoulder harm.

When searching for core workout routines on-line, you will encounter quite

so much of uncommon and spectacular routines designed to strengthen your

core. Nonetheless, amidst all these options, it is simple to

miss th… This exercise is performed on your facet to alter the angle of resistance and target the obliques

and transverse abdominal muscular tissues. Battle ropes are versatile they usually come in numerous diameters and lengths to allow

you to focus either on muscle endurance and conditioning or strength and energy.

This unilateral version makes it attainable to raise your hand larger and get an extended stretch on the bottom, thereby generating more work for the posterior deltoid.

You can use varied attachments with the cable that can hit nearly every muscle group a technique or another.

The deltoid muscle of the shoulder consists of three separate sections or

heads. If you’re not utilizing cables for shoulder work, you’re leaving a lot of potential on the load room ground.

This full-body transfer requires continuous actions of your legs

and arms without pausing. You can tweak your arm exercise

to incorporate bicep curls by switching between load weights.

It is active during elbow extension when the forearm is supinated or

pronated.

As your arms work the ropes, your core, glutes, and again work to keep

you upright and stable. You can work out and practice in strength, hypertrophy, endurance, power, and

cardio with out ever leaving the ropes. You can create an entire

exercise with the ropes and focus in your shoulders with just

a few easy strikes. I saved the best/hardest for final – Battling Rope Shoulder Series.

Over the past few years, I’ve been using the ropes

extensively with my athletes. After my athletes have

done prone shoulder circuits for 4-8 weeks I will start

to implement extra band-resisted shoulder complexes.

With these three circuits the athlete might be standing which would require

them to interact their anterior core all through

the length of each set.

Improved function and strength may help you fully get well after a shoulder surgery

damage. You can even change up your grip of the attachment on the

cable machine with ease to carry out a massive number of workout routines effectively and safely.

Cable pulley machines apply fixed rigidity in your

muscles. One major difference between doing back workout routines with free

weights and a cable machine is that you’re capable of change up angles and positions.

We are so accustomed to creating motion within the sagittal airplane,

that the motion forces a cerebral influx. Enhancements in variability and connection for our central

nervous system and peripheral nervous system will improve common and world coordination for life and athletics.

This full physique tri-planar movement is explosive and powerful… and

it just looks really really cool for the mover and

the spectator.

You are pulling one thing toward you, a lot in the identical method I think about people of the hunter-gatherer tribes of the stone ages and agrarian societies of antiquity doing on a regular

basis. I want that water, animals, vegetation, human over here,

so I will tie a rope around it and pull it towards me.

Now that you understand I actually have weird ideas flying through my mind,

you can do it for aesthetic or efficiency reasons, as an alternative of my early

human identity reasons. Shoulder pulleys are an instance of an train your bodily therapist could

implement to assist you regain passive ROM. Once passive ROM is restored, you could progress to active-assistive ROM exercises and,

lastly, lively ROM workouts like the ones in this program.

Not many single items of fitness center tools have the power to

target each space of the shoulder. The whipping motion is kind

of like an explosive rear delt fly to chest fly. As such, your arms, shoulders (rear delts and front delts in particular), chest,

traps, and rhomboids shall be emphasised essentially the most.

Sure, you possibly can construct your muscles utilizing

just the cable machine, as lengthy as you comply with a well-structured program that focuses on the most effective cable exercises for strength and hypertrophy.

With cables, you’ll be able to target the muscular tissues from multiple

angles in a secure and effective way. Cables may be adjusted at different heights

to realize resistance going in particular directions. In all cable machine shoulder exercises,

this can benefit the deltoids as you possibly can set the cable to go in line with the course of the muscle fibers.

The other smaller teres muscle, this narrow-rounded muscle is

a half of the rotator cuff. It starts at the scapula and inserts into the humerus and the joint capsule.

Both advanced lifters and novices can get plenty of out doing back workout routines with a cable.

Advanced lifters would possibly need to target

a specific smaller supporting muscle such because the teres major/minor or

the infraspinatus. A variation of the seated row, the

shut grip row shifts the primary target to the mid again. With this train you want to be capable of raise heavier weight compared

with the wide grip row as a outcome of your lats are doing most of the work here.

The cable chest press is a variation of the barbell and dumbbell bench press.

Because it’s lots safer than the free-weight versions of the

train, it’s the go-to for many newbies and these that are recovering from damage.

Different forms of ropes have different weights, textures, and handles, which can have an result on your grip,

wrist and arm movement, and general flow. Strive different ropes similar to

velocity ropes, weighted ropes, and thicker ropes to

find those that work finest in your circulate. Rope circulate workout routines are nice for building muscular power, increasing cardiorespiratory fitness, and enhancing athletic efficiency.

As you spin and manipulate the rope, you’re utilizing

your arms, shoulders, and core muscular tissues to

manage the motion of the rope. For this reason, it is smart to have seen so

many anecdotes about people having enhancements in cardio endurance and conditioning after incorporating rope

circulate workouts.

Shoulder cable exercises primarily work the deltoid muscle tissue, which are answerable for shoulder motion and stability, as nicely as the higher

again and trapezius muscles. Cable shoulder exercises assist to improve general shoulder energy, stability, and muscle definition, all of which

are key advantages of workouts that focus on the shoulder muscle tissue.

Additionally, cable shoulder workouts might help

to enhance posture and reduce the risk of harm to the shoulder joint.

They are particularly helpful for athletes who participate in sports activities that require upper

physique strength and stability, such as swimming,

baseball, and tennis. Cable shoulder exercises are best for focusing on the muscle tissue of the shoulder, together with the deltoids,

rotator cuff, and trapezius. Cable exercises provide constant tension on the shoulder muscle all through the entire range

of movement, allowing for more effective contraction.

It’s probably the greatest trap workout routines for

isolating the center trapezius greater than you’ll have the

ability to with rows. It contributes to raised shoulder well being and gives you that nice, rounded look to your shoulders.

They may be dumbbells, kettlebells, or particular farmer’s

stroll bars. As long as you’ve equal weight in each hand, you’re good to go.

You can even do upright rows utilizing dumbbells or a deal with hooked up to a

pulley system.

A., Rosenberg, J. G., Klei, S., Dougherty, B.

M., Kang, J., Smith, C. R., Ross, R. E., & Faigenbaum, A.

D. Comparison of the acute metabolic responses to conventional resistance, body-weight, and battling rope workouts.

This workout program could be adjusted to make it simpler

or harder by including additional sets or altering the amount of time of relaxation or work.

That being said, it would be greatest to do a shorter variety of

reps due to the facility required to carry out this train. Being seated completely eliminates any lower-body muscle activation and

shall be a very efficient upper-body workout.

Adding the lean to the exercise will help you acquire barely extra vary of movement.

This will allow the cables to be in the optimum place to stretch the muscle

fibers and subsequently maximize the range of motion, which is essential for maximizing the hypertrophy stimulus.

This is helpful because it means you possibly can practice tougher and bring the shoulder muscle tissue nearer to

failure together with your units to offer it a better stimulus.

This exercise offers stability and mobility to

the shoulders and helps balance the energy of opposing muscle teams,

which is necessary for joint well being.

Do you need to tone up your shoulders and obtain the body of your dreams?

However at all times keep in mind to add dumbbell

and barbell workouts together with cables to offer the right shape and measurement to

your shoulders. Do each the exercises together without any relaxation in between every

set. Some people can not use rear delts during fly workout

routines due to lack of thoughts and muscle connection. Whether you’re getting

battle ropes as a newbie or you’ve been working the fitness center for years,

you can use the battle ropes to create the ideal exercise program.

Then, raise your arms up and out to kind a Y shape along with your

physique. Maintaining these muscles healthy is vital to avoiding shoulder pain or injury.

Workouts that concentrate on inside rotation, external rotation, and lifting your arms

can help lots. Robust rotator cuff muscle tissue imply you can do more activities with out worry

of injuring yourself. Cable workouts maintain your shoulder muscular tissues underneath

constant pressure all through the entire movement.

This means those muscle tissue work tougher for longer, which may lead to better progress and energy.

Usually, sure, battle rope workouts are supposed to be full body, both for endurance and fat loss or explosive strength and fats

loss, or each. Battle ropes are funnest and best when used as they are designed – undulating waves, whips, slams, and

circles, as properly as pulls. Single-arm lateral raises are a preferred

cable shoulder exercise to add to your routine.

The right exercise for you’ll rely upon the prognosis and symptoms of

the situation inflicting the muscle ache. The physiotherapist should

strive to determine what caused the pain when it first started and what conditions made it higher or worse to fastidiously examine the muscle ache in your shoulder.

After that, the physiotherapist will recommend workout routines for you based on the causes of your muscle

ache. The guillotine press scored relatively low in the German study.

The TRX Shoulder Scarecrow is an efficient shoulder train focusing on shoulder mobility, stability,

and strengthening of the rotator cuff muscular tissues.

This exercise helps improve posture and shoulder joint health whereas focusing on the muscle tissue answerable for shoulder exterior rotation. TRX Alligators problem not

only the shoulder and chest muscle tissue but also the core and obliques due to having to

keep up a plank place. This exercise enhances higher body energy, stability, and coordination while

providing a dynamic challenge compared to conventional workouts.

With workouts like lateral raises, upright rows, and face pulls, you probably can totally develop

your shoulders using cables alone. Cable exercises present constant rigidity, making them more

effective for muscle activation compared to dumbbells.

In truth, rope circulate is becoming increasingly well-liked as

a approach to manage stress and improve mental well-being.

For instance, as you bounce on the balls of your toes while training rope move, you are encouraging the move of lymph round your body.

This flexibility makes rope flow an accessible and adaptable activity for folks of

all abilities. You can modify the velocity and intensity of your rope circulate practice by spinning the rope slowly or shortly, and

by utilizing a lighter or heavier rope. Rope flow is an activity that’s straightforward for most people

to learn, as most of the movements are already acquainted.

If you’re seeking to goal a specific area, you possibly can change the way you

swing the ropes by learning the totally different patterns like underhand sneak and overhand sneak

in addition to the dragon roll.

References:

build muscle steroid

I adore your websites way of raising the awareness on your readers.

I really loved reading your blog. It was very well authored and easy to understand. Unlike other blogs I have read which are really not that good.Thanks alot!

If your looking for Online Illinois license plate sticker renewals then you have need to come to the right place.We offer the fastest Illinois license plate sticker renewals in the state.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

70918248

References:

non Steroid bodybuilders (talukadapoli.com)

I want you to thank for your time of this wonderful read!!! I definately enjoy every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff of your blog a must read blog!

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://www.binance.info/en-IN/register-person?ref=UM6SMJM3

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://www.binance.com/register?ref=IHJUI7TF