With the Food and Drug Administration likely to authorize Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years old, the last major phase of the U.S. vaccination roll-out may soon be underway. We previously explored policy considerations for vaccinating 5-11 year-olds, who became eligible in November of last year, and have been tracking vaccination progress among this group, both of which may be instructive for this next phase. However, there are unique issues to consider for younger children that may present additional barriers and issues for policymakers, public health practitioners, and parents and caregivers. This brief provides an overview of the characteristics of children under the age of 5 nationally and by state and discusses some of the particular issues to consider in rolling out vaccination to this age group.

What are Characteristics of Children Under Age 5?

There are approximately 19 million children under the age of 5 in the United States. They account for 6% of the U.S. population. The share of the population represented by young children varies by state, ranging from a low of 4.6% in Maine to a high of 7.7% in Utah. Data about the size and composition of children under age 5 across the country come from the 2019 American Community Survey. Due to data on age only being collected in years, we include all children under the age of 5, including children less than 6 months old who would not be eligible to receive the vaccine under this authorization.

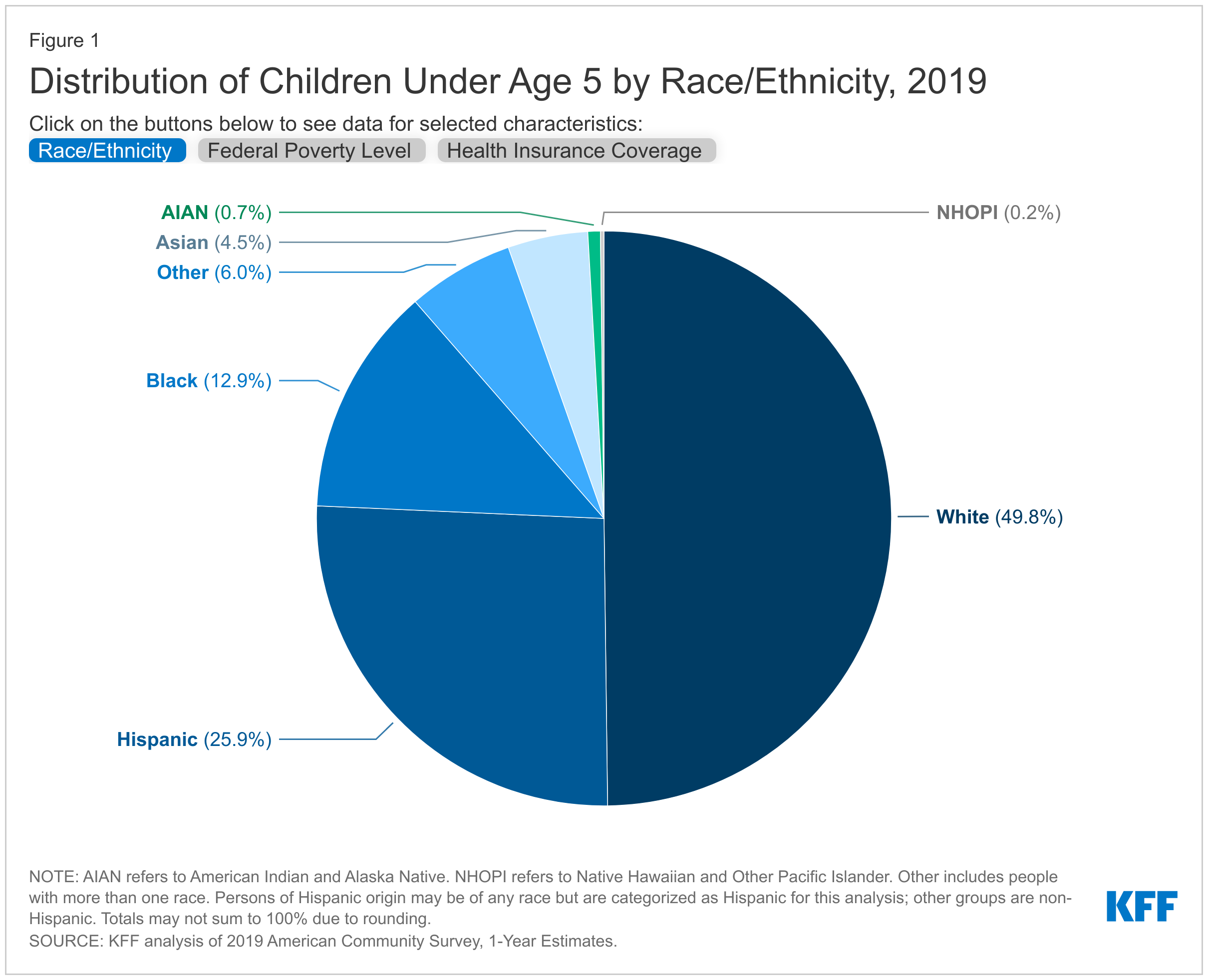

Half of children under the age of 5 are children of color, including more than a quarter who are Hispanic (25.9%), 12.9% who are Black, and 4.5% who are Asian (Figure 1). Smaller shares are American Indian or Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (<1 % each). The distribution varies across the country (Table 1). For example, in four states, a third or more of younger children are Black – Georgia (32.7%), Louisiana (34.1%), Mississippi (41.7%) and DC (43.7%). States in the West and South include higher shares of Hispanic children; at least half of younger children are Hispanic in New Mexico (62.4%), California (51.3%), and Texas (49.8%).

Four in ten children under the age of 5 live in a family with income below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), including 18.1% below poverty and 21.9% between 100-200% FPL (Figure 1). An additional 29.8% live between 200-400% FPL and 30.2% are above 400% FPL. This income distribution varies significantly by state (Table 2). For example, the share living in a low-income family (below 200% FPL) ranges from 23.9% in New Hampshire to 56.3% in Arkansas. In four states, the share living below 200% FPL is greater than 50%; In 5 states, more than a quarter of younger children live below the poverty level.

Just over half of children under the age of 5 have private insurance coverage while 41.3% are covered by Medicaid/CHIP, and 4.5% are uninsured. This too, varies by state (Table 3). For example, the share of young children who are privately insured ranges from 35.7% in Mississippi to 72.8% in Utah, while the share covered by Medicaid/CHIP ranges from just 19% in Utah to 64% in New Mexico. The share of young children who are uninsured ranges from 1.3% in Massachusetts to 9.8% in Texas.

How will vaccine roll-out to children under 5 be similar or different to 5-11 year-olds?

Many of the issues that have affected vaccine roll-out to 5-11 year-olds will likely apply in the case of younger children as well, including access challenges in some places. As with 5-11 year-olds, access will likely vary across the country, depending on jurisdictional decisions and implementation plans, the number and location of pediatric vaccinators and sites, the adequacy of provider networks, and communication and outreach plans. Unlike with adults, for example, where vaccines have been widely available at multiple locations to reach the close to 260 million who are eligible, the small population size of children has meant fewer locations with vaccines, an issue that has created access barriers in some rural areas, for example.

COVID-19 vaccination for children under age 5 will require yet another formulation and new doses and supplies to be shipped. One issue that arose during the roll-out of vaccination to 5-11 year-olds was that their vaccine dosage was lower than that for adults and required new vials to be shipped out to states and pharmacies. This delayed access in the beginning days of eligibility and has meant the vaccinators have had to specifically order and stock pediatric vaccines. For those under 5, there will be an even lower dose, again requiring new shipments to jurisdictions. This may once again hold up vaccination opportunities in the early days of authorization.

Pharmacies and schools, while important components of the COVID-19 vaccination effort for older children, will be less likely to reach those under 5. Many states limit the age at which pharmacists are allowed to vaccinate children. To address this issue in the context of COVID-19, the federal government amended the PREP Act under the COVID-19 public health emergency to allow pharmacists and pharmacist technicians to vaccinate children as young as 3 for routine immunizations as well as against COVID-19 (upon authorization). However, the Act has not been amended to allow for children under 3 (who account for almost 60% of all children under 5) to be vaccinated at a pharmacy, and according to data from the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations (NASPA) and American Pharmacists Association (APhA), most states do not permit this. In addition, while schools have been important sites for providing access as well as information to help expand vaccination take-up among children as young as 5, and have been encouraged by the federal government to do so, most children under 5 are not yet enrolled in school, limiting this option for younger kids.

Pediatricians will likely be more important for vaccinating young children than even their slightly older counterparts. Pediatricians, who are already cited by parents as their as their most trusted source of information about COVID-19 for children, will likely play an even more important role in vaccinating children under 5. This is in part due to the more limited access to vaccinations at pharmacies and schools, but also because parents are even more accustomed to getting their routine immunizations for younger children at their doctor’s offices. Still, pediatricians face unique challenges with pediatric COVID-19 vaccinations for children, including those ages 5-11, relative to other vaccinations. In addition to cold storage requirements, a COVID-19 pediatric vaccine vial, which contains 10 doses, must be used within 12 hours after opening. This means that pediatricians, or any other pediatric vaccinator, would need to be able to vaccinate 10 children within this time period or risk wasting doses.

Medicaid will be an especially important avenue for reaching younger children, as will community health centers. Among all children under age 5, over four in ten (41.3%) are covered by Medicaid, and almost three-quarters (74.1%) of children under age 5 with incomes below 200% of FPL are covered by Medicaid. We previously identified how state Medicaid programs and Medicaid managed care plans can facilitate access to vaccines for young, low-income children. In addition to these strategies to increase vaccine uptake, CMS recently announced they will provide 100% federal Medicaid matching funds to states to cover COVID-19 vaccine counseling visits for children with Medicaid. Community health centers also offer vaccine access points for families with young children. A national network of safety net primary care providers, they are a primary source of care for many low-income populations (91% have incomes below 200% FPL) and communities of color (62%), and they have already been mobilized to provide vaccinations to their clients through the federal Health Center COVID-19 Vaccine Program. Community health centers serve between 5 and 6 million children under the age of 12, including about 2 million under the age of 5.

As with 5-11 year-olds, parents and caregivers will determine how quickly and how many younger children get vaccinated. Our latest COVID Vaccine Monitor report found that three in ten (31%) parents of children under 5 say they’ll get their child vaccinated against COVID-19 right away once a vaccine is authorized, 29% say they will wait and see, and almost 4 in 10 say they won’t get their younger child vaccinated at all or only will if required. If the experience of vaccinating 5-11 year-olds is a guide for what might happen with younger children, vaccination coverage will likely be quite slow. While the share of parents of 5-11 year-olds who say they have or will get their child vaccinated has increased over time, a third still say they will not do so, or will only do so if required. Our analysis of vaccine coverage among 5-11 year-olds found that while vaccination rose sharply for the two-week period after eligibility, it then dropped steeply and daily rates of administration have remained low. As of February 2, just 22% of children ages 5-11 have been fully vaccinated.

Prioritizing equity is particularly important as vaccination efforts extend to the youngest group of children. Of the estimated 19 million children in the U.S. under age 5, half are children of color (compared to 40% of the U.S. population overall), including more than a quarter who are Hispanic (25.9%) and 12.9% who are Black. Black and Hispanic people have been less likely than their White counterparts to have received a vaccine over the course of COVID-19 vaccine rollout; though racial disparities in vaccination rates have narrowed over time and have closed for Hispanic people. Disparities in children’s take-up of the vaccine could reverse that trend. Another KFF COVID Vaccine Monitor report found Hispanic parents, Black parents, and parents with lower incomes were more likely to say they might have to miss work to get their child vaccinated, that they won’t have a trusted place to go, or that they’ll have difficulty traveling to a vaccination location compared to other parents. To mitigate similar disparities in vaccination rates among children, it will be important to address potential access barriers, ensure vaccinations are available through trusted sites, and address parent/caregiver concerns and questions through trusted individuals in the community. Data on vaccination rates for children by race and ethnicity is important for being able to identify disparities and to direct resources to address them. However, the federal government is not currently reporting vaccinations among children by race and ethnicity, and only a handful of states report these data.

What Happens Next?

The FDA has scheduled an advisory committee meeting on February 15 to review and vote on Pfizer’s emergency authorization request for children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years old, which will be followed by an FDA decision (though the FDA is not bound by the advisory committee’s vote). The decision-making process then moves to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices ACIP), which makes its recommendation to the CDC Director who ultimately will make a final decision about whether the vaccine will be administered to younger children and provide guidance to states and vaccinators on reaching this group. The White House has said it will move quickly to get the new vaccine formulation and related supplies out to jurisdictions, if the vaccine is authorized for younger children. Then, many of the factors explored here will collectively influence the speed and extent to which the millions of children under the age of 5 are vaccinated against COVID-19, and engaging pediatricians, parents/caregivers, state Medicaid programs, and community health centers will be especially important.