“When I started MetaLab in 2006, the idea of handing anything off seemed insane,” says Andrew Wilkinson, the Founder and CEO of the Canada-based digital product agency on his Medium blog. Today, MetaLab’s clients include Uber, Slack, Amazon, Apple, Google, Mozilla, TripAdvisor, Tumblr, and Walt Disney. But the success did not come easy for them.

In 2009, when it was still a small but profitable agency, Wilkinson recognised that his “biggest problem at the time was managing people. I was up to about 10 employees and I was having trouble keeping track of what everyone was working on.”

They started developing the project management service Flow and launched the beta version nine months later. It was to scratch an itch. “We were frustrated with having to use three different apps to manage our daily workflow, so we decided to build a solution ourselves,” says Wilkinson.

“We broke all the rules. We didn’t raise money, worked short days, and even did client work on the side. And yet just three weeks after launching, Flow was turning a profit. One year later, we’re bringing in over US$500,000 in recurring revenue and growing like crazy,” says Wilkinson.

He borrowed an idea from Basecamp, building software for themselves and then selling monthly access to it.

From day one, it was a huge hit. A lot of people had the same problem and there was nothing else like it. Wilkinson was “in love” with this business model.

Andrew Wilkinson, Founder and CEO of MetaLab, a Victoria-based software company. Image Credit: martlet.ca

When Flow added subscriptions, the service reached US$20,000 in revenue in its first month, growing 10 per cent on a monthly basis. Flow offered a 14-day free trial followed by a subscription for US$10 per month or US$99 per year.

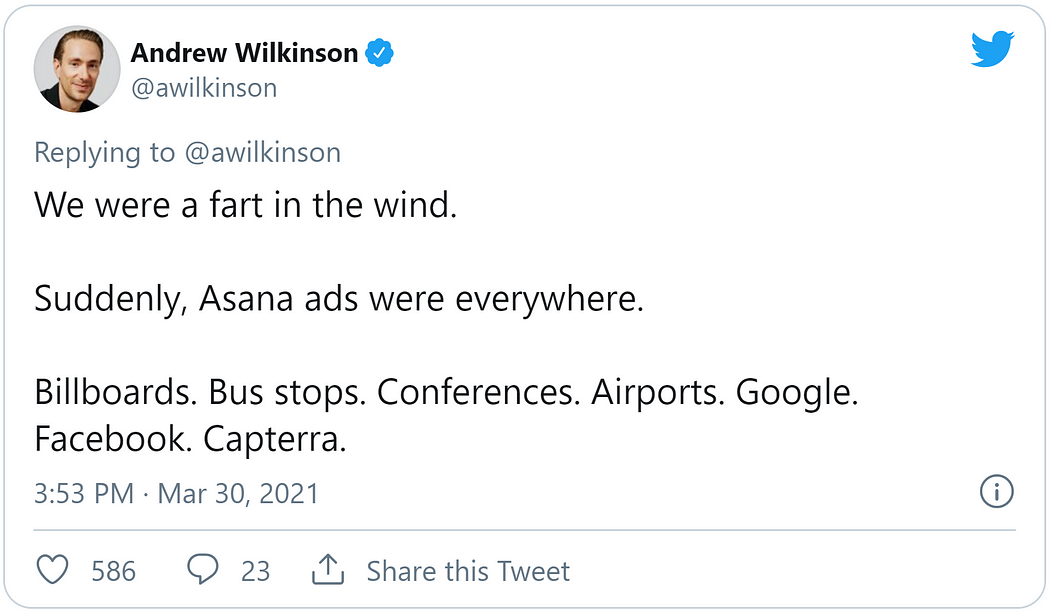

“There was just one problem: I was consistently spending two to three times our monthly revenue and losing money. And not venture capital. Out of my personal bank account,” Wilkinson writes. He constantly reassured the CFO and considered him shortsighted; Wilkinson believed that the service would bring “Millions! Maybe billions!” so more investment was needed in it.

First appearance of Asana on the market

TechCrunch wrote in 2011 about Flow. “If you’re looking for an alternative to GTD lists, Outlook, or Basecamp, it’s certainly worth checking out.” But they also recognised that the service will also be competing with Asana, the site founded by Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz who has been Mark Zuckerberg’s college roommate.

Founders of Asana Dustin Moskovitz and Justin Rosenstein (who left Google in 2007) met while leading Engineering teams at Facebook. They left the company in 2008, to start a company whose product would allow teams to work together more successfully, eliminating much of the “work about work”.

Also Read: Today’s top tech news: Asana plans for direct listing, Fleetx raises US$2.8M in Series A

Asana co-founders Justin Rosenstein (left) and Dustin Moskovitz. Image Credit: Asana

Wilkinson notes that the name Asana “started popping up quietly at first, then a lot”. However, when the service launched, Wilkinson breathed a sigh of relief: “It was ugly! It was designed by engineers. Complicated and hard to use. Not a threat in the slightest.”

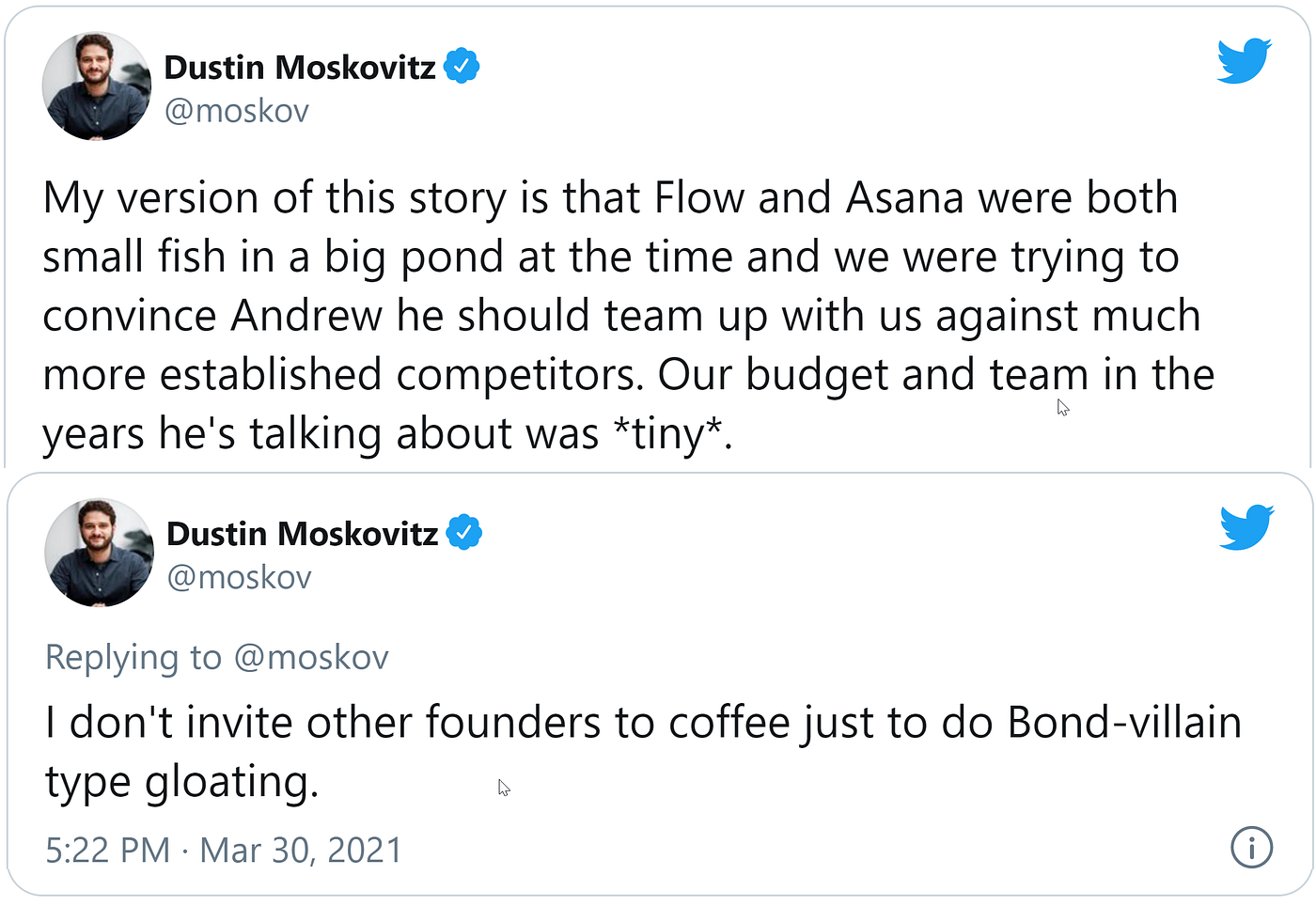

Around the same time, Moskowitz invited Wilkinson for coffee in San Francisco.

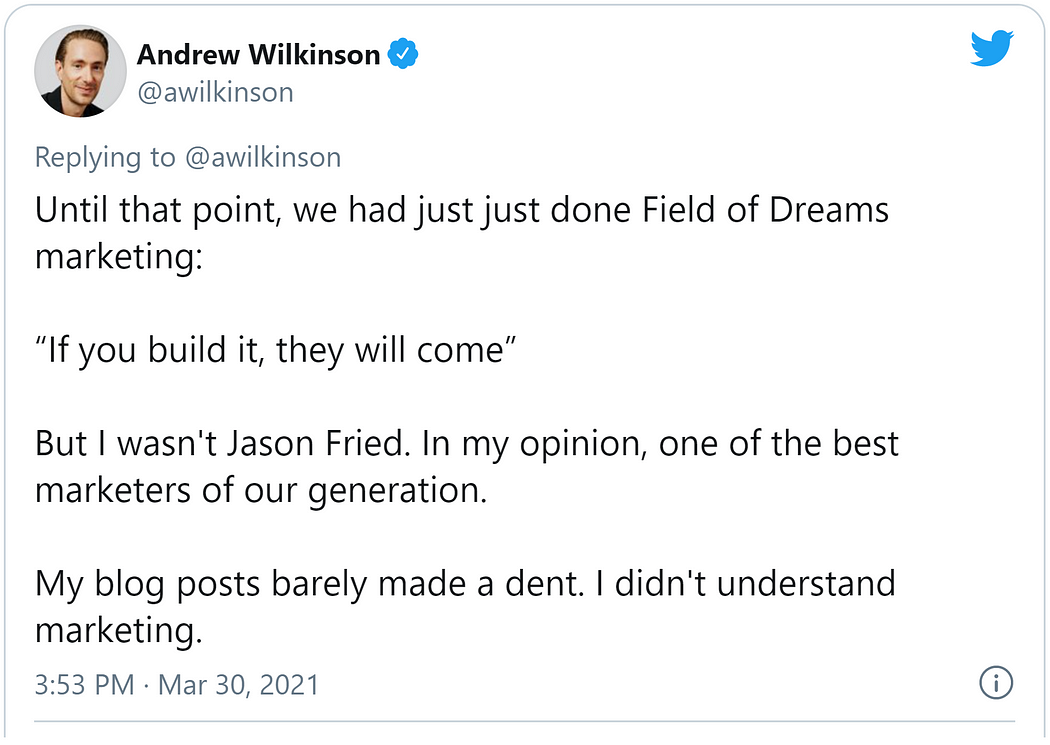

“He walked me through who was backing them, how much cash they had, how they had hired top executives from huge companies, and that it was only a matter of time until they beat us on product and outspend us on marketing,” Wilkinson says. “He implied — in the nicest possible terms — that they were going to crush us. I laughed! ‘Nice try!’ and told him ‘let the games begin’,” writes Wilkinson.

A fart in the wind

Wilkinson believed that they had built what he felt was a superior product: the service continued to grow rapidly, users demanded a version for all platforms — iPhone, Android, iPad, Mac.

Asana quickly released clients for all platforms — it had five times as many developers as Flow, Wilkinson writes. “Suddenly it was a key feature when people compared Asana and Flow side-by-side. Mobile was table stakes,” he adds.

The entrepreneur continued to invest until they ran out: the company began to delay missing payroll and rent. Wilkinson writes that one day his business partner Chris Sparling even had to inject cash from his personal account so they wouldn’t miss payroll. By that time, he had already spent “millions of dollars.”

Asana then raised US$28 million in investment and started investing in marketing, while Flow viewed paid marketing as “douchey and aggressive” and focused on organic growth.

In an attempt to regain the market share, Flow started spending on advertising but mostly continued to focus on “making the product better than theirs”. This was the only remaining benefit of the service, but the product also began to suffer: the company did not have the money to hire more developers.

With a team that is a quarter of the size and a fraction of the money, service growth began to slow down as the company received an “endless stream of bug reports.” Meanwhile, Asana continued to hire a “huge team of incredible designers”. Flow’s team felt frustrated and under-resourced and they churned through staff.

Also Read: This project management tool from Cambodia wants to give Trello, Asana a run for their money

“One day I woke up to see that Asana had fully relaunched. Their marketing site looked … great. Better than ours … Their new app, while not perfect, had all the features we wished we had time to make, worked on more platforms, and most importantly, was fast and not buggy.”

“Even our own keywords on Google were crammed with “Asana vs. Flow” paid links. By this point, they were burning over US$150,000 per month,” says Wilkinson. “It was like Fiji waging war on the US with a collection of AK-47s and speed boats vs. artillery and aircraft carriers.”

The writing is on the wall

Then Flow decided that they didn’t need to “own that market”. They could just have a small slice of pie. They focused on base hits. For a while, that looked like an OK strategy. The revenue growth slowed, but still kept on growing.

Until one day it didn’t.

“Churn caught up with us, customer acquisition cost became unprofitable, bugs continued to dominate our time, and Asana and others kept making their product better,” Wilkinson says. “Twelve years and over US$10 million lit on fire, we are done burning money in a losing battle. We give up.

The writing is on the wall. Dustin was right.”

The company downsized and relocated the team to India to break even and support the remaining customers. At the peak of its business, Flow received about US$3 million in annual revenue, and now the average is US$900,000 per year.

Flow “lost” due to inexperience, grocery “myopia” and lack of capital, concludes Wilkinson.

Also Read: wagely bags US$5.6M to give Indonesia’s low-paid workers access to their earned wages

Wilkinson highlighted the key lessons

- If you are in a competitive VC-funded space, it’s foolish to compete without raising money. Don’t bring a knife to a gunfight.

- The best product doesn’t always win, and the product is not a long-term competitive advantage.

- If a tree falls in the forest and nobody is around to hear it, it didn’t fall.

- Every developer in the world wakes up thinking “I should build a to-do list app” and people love jumping between productivity apps and workflows. There is no moat in productivity — avoid it if you can.

- Running a SaaS business without deeply understanding churn, LTV, CAC, etc, is like flying a plane without instrumentation — really stupid and dangerous.

- Failure sneaks up on you slowly, then all at once.

- R&D is expensive. Especially when competing with venture.

- If you’re competing on features, it never stops and is an ever-increasing line item.

- Good product with great marketing beats amazing product with no marketing.

- Bootstrapping works best in uncompetitive spaces/niches, or if you have an unfair advantage (a personal brand, unique customer acquisition channel, etc).

Dustin Moskowitz responded to Wilkinson’s thread: in his version of the story, he “did consider @awilkinson and team’s product to be a very high quality player in the space and respected the hell out of them”.

Editor’s note: e27 aims to foster thought leadership by publishing views from the community. Share your opinion by submitting an article, video, podcast or infographic

Join our e27 Telegram group, FB community or like the e27 Facebook page

Image Credit: tomwang

The post How Flow creator Andrew Wilkinson lost US$10M by doing “something stupid” appeared first on e27.