Tony Sammartino has no idea when he will next hug his three-year-old daughter, but it’s almost guaranteed it won’t be for another year at the earliest.

“These are the best years of her life, and they should be the best of mine too. And they’re slipping away.”

Tony hasn’t seen Maria Teresa, nor her mother and his partner, Maria Pena, since March 2020, when he was in the Philippines with their other daughter, Liliana.

Before the pandemic, the family of four split their lives between Melbourne and Subic, a coastal city north-west of Manila, spending roughly half a year in each parent’s home country.

Now, the Sammartinos are one of countless Australian families that find themselves separated by an almost hermetically-sealed border, an enduring aspect of Australia’s harsh response to the pandemic that continues to prevent even its own citizens from freely returning to or leaving their country.

Some 40,000 Australians have at any one time remained stranded overseas, missing births, funerals, losing jobs, and even dying from Covid despite pleas for help to return home.

As countries around the world vaccinate their populations and reopen to freer travel, Australia – which has recorded 910 deaths from Covid-19 and zero community transmission for most of this year – is progressively tightening its borders.

The hardline approach appears to have gained support among the Australian public, with demographers and sociologists observing Australian leaders’ attitudes towards risk management had shifted Australians’ views about being global citizens, with other experts pondering: what does it say about the collective Australian psyche that a proudly multicultural country can be so supportive of such strict border closures?

‘There has to be a solution sooner’

At the beginning of the pandemic, a permit system was introduced for those wanting to leave Australia, with even some compassionate pleas rejected.

A strict mandatory hotel quarantine system was introduced to absorb an influx of returning citizens – about one million Australians lived overseas pre-pandemic.

Then in July 2020, a cap was placed on the number of people quarantine hotels would process, leading to months of flight cancellations, and an almost impossible equation for airlines to remain profitable on Australian routes.

Seat prices on airlines that continued to fly into the country soared by tens of thousands of dollars, with jumbos flying as few as 20 passengers per flight.

Meanwhile, the prime minister, Scott Morrison, routinely rejected calls to build purpose-built facilities to repatriate more citizens, insisting state governments were responsible for quarantine.

The country’s border crackdown peaked at the end of April this year, when Morrison used sweeping biosecurity laws to issue a directive threatening to imprison any citizens who attempted to fly to Australia from India via a third country while a temporary direct flight ban was in place during the recent outbreak.

While a travel bubble was established with New Zealand in April, repeated delays to Australia’s vaccine rollout have made the government hesitant to announce a timeframe to reopen its borders.

After the government revealed an assumption in its annual budget last week that the border would remain shut to international travel until after mid-2022, Tony is struggling with the lack of outrage at the policy.

“I haven’t really absorbed that, because I know for me there has to be a solution sooner, it can’t take that long for them to come home.”

Like many Australians, Tony’s partner was born overseas, and was not a citizen or permanent resident when the pandemic began. As the parent of an Australian born child, she could apply for a visa and exemption to Australia’s border ban on all non-citizens, however she cares for a child from a previous relationship in the Philippines, who would not be able to gain entry to Australia.

Meanwhile, Maria Teresa is too young to travel alone, while Tony cannot secure an exemption and flights for him to travel to escort her to Australia, where he had been planning to enrol her in preschool. He does not want to risk becoming stranded in the Philippines indefinitely.

This hasn’t stopped Tony waking up at 4am most mornings from the stress of his situation, and going online to search for flights. He has become obsessed with flight radars, to monitor the few passenger flights that still enter Australia each day, to calculate how many passengers they are carrying and what a route home for his daughter and partner might look like.

“I just don’t have the money to fly there, and pay $11,000 each to fly home, and then quarantine (about $5,000). If you had money, could you get here easily,” he said, a reference to international celebrities who have paid their way into Australia.

The family FaceTime call everyday, but Tony is worried their other daughter, Liliana, is losing interest in her mother, frustrated she is missing milestones in her life.

“The embassy in Manila doesn’t help, but they sent us a link to a charter flight company in Hong Kong. The government has left us on our own. They haven’t beaten Covid at all, they’ve just shut us off entirely from it,” Tony said.

A ‘Noah’s Ark model of survival’

Only one-third of Australians believe the government should do more to repatriate citizens, a recent Lowy Institute poll showed, and the Morrison government appears to be banking on the political safety of a harsh border policy as a federal election looms on the horizon.

Dr Liz Allen, a demographer at the Australian National University, said the popularity of Australia’s Covid strategy was not surprising.

She said despite the fact that about one in three Australians born overseas, “protectionist narratives have operated quite successfully in Australia”, particularly because of an older population.

Prof Andrew Jakubowicz, a sociologist at the University of Technology Sydney, is not surprised by the “cognitive dissonance” occurring in a multicultural nation supportive of the border closures.

“Something deep in the Australian psyche is the memory of how easy it was to invade this place, the idea that the moment you let them in, you’re in trouble,” he said.

Jakubowicz pointed out that migrants to Australia are often the most opposed to further migration. “There’s a long history of pulling the gate shut once they’re through the door.

“It’s this learned apprehension of letting in, it’s allowed us to accept hardline immigration policies in the past, and it’s allowed us to reprogram quickly to the stress of being stuck here in the pandemic.

“The government has looked at the states’ popularity with their borders, and it’s comfortable with this Noah’s Ark model of survival,” Jakubowicz said.

Allen agrees, and believes the government’s strategy plays into Australians’ sense of security.

“Australia has not done anything marvellous or miraculous in containing Covid, it’s been about geography and dumb luck. We’ve dug a hole and stuck our head in it and that’s where we will remain.

“We like to view ourselves as larrikins and irreverent people who stand up to authority, but in reality we are scared, we’re petrified. We’ve become so comfortable because of our geography that we’re losing our greatness.

“We’re not even able to have a conversation about risk, the government is too scared of championing new quarantine facilities out of fear if something goes wrong,” she said.

Allen believes the country “risks regressing” both culturally and economically without reopening to immigration, tourism and family reunions.

On Friday, a coalition of business, law, arts and academic figures echoed this call, urging the government to adopt a “living with Covid” strategy to avoid reputational damage to Australia.

“Australia benefits tremendously from our migrants and tourism. Year on year, this country has spruiked the wondrous kind of living conditions in this place to all corners of the world, to come join us.”

“But now, so many who have made Australia their home, and taken a risk on us, we tell them to go home. Well they were home,” Allen said.

Forced into financial ruin

This sentiment is shared by Vamshi Parepalli, who lives in Melbourne with his wife Shruthi having gained permanent residency status. In December, the couple gained an exemption and travelled to India to care for his mother in Hyderabad, having failed to get approval for her to come to them in Australia.

They have now become stuck amid India’s devastating outbreak. Not only have there been no direct flights home, they face a $66,600 fine and five years in jail if they attempt to return via a third country.

“How can it be criminal to return to our home? To be honest, I feel like it was a dream when I got my residency and stepped into Australia, and now it looks like it really was just a dream,” Vamshi said.

In other countries, Australians left in limbo have been unable to work, forcing some into financial ruin.

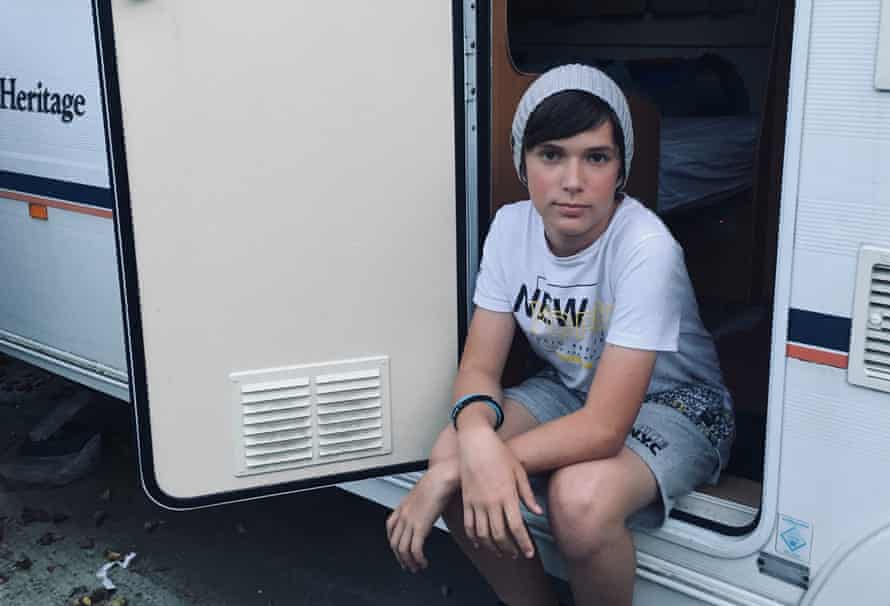

The Vowels, a family of seven who live near the city of Newcastle, north of Sydney, spent more than half a year living in a camper van in their cousin’s backyard in Crawley, England, after their initial flights home from a family holiday were cancelled. Intense media pressure saw them offered flights home that would have otherwise cost them $113,000.

However, Andre Rivenell is still living in a camper van. He has been stuck with his wife in Texas since their initial flight home was cancelled when the pandemic first hit. His health deteriorated after a stroke and diagnosis of a chronic autoimmune neuromuscular disease, and he cannot afford healthcare in the US.

He hopes to return home to see his son before he dies, however the Australian government did not approve him for an emergency loan initiative for vulnerable Australians stranded overseas.

Meanwhile, Tony Sammartino was met with backlash from someone in his local park after hearing his family was separated – a perception those overseas travelled frivolously and have had time to come home.

He is worried this is representative of a larger lack of political support for any change in the policies.

Allen believes the public backlash against those stranded is linked to “an arrogance that we’ve fought a pandemic and won a war”.

“We didn’t win a war, we’ve just bunkered down. We’re a bunch of preppers, and we’ve gone in with baked beans and tinned spaghetti. There’s so much more to life than baked beans and tinned spaghetti.”

This content first appear on the guardian

This variation will still work the core however to a a

lot lesser extent the glute. Strive to keep the opposite foot off

the bottom throughout the set. No one wants need side of their physique extra developed than the opposite facet, so be certain to complete all

of your reps on one facet, before turning round and finishing all reps on the opposite

side. Lastly, our scientific evaluation board reviews the

content to make sure all key info and claims are backed by high-quality scientific analysis and defined merely

and exactly. If you’re feeling that any of our content material

is inaccurate, deceptive, out-of-date, or anything lower than factual, please let us know within the feedback part of the article in question. This allows them

to not solely evaluation particular person studies

but also analyze the general weight of the evidence

on any and all subjects associated to diet, train, supplementation, and more.

Legion’s content material is fact-checked and reviewed by a team of scientific, medical and

subject-matter specialists to make sure everything we publish is proof primarily

based, trustworthy, and current.

There are literally many other core workout routines you can do to strengthen your obliques,

abdominals, and surrounding muscle tissue, and one of the underrated is the Pallof press.

Instead of teaching you to crunch, curl or twist, it trains your midsection to withstand motion and “maintain it right there” for phenomenally robust abs.

It puts zero stress on your wrists or again, you do it

standing up and it hits all 360 levels of your core. Fight

the pull of the cable or band by preserving your glutes and core tight.

●Kneel subsequent to the anchor level and grasp the band or cable handles

with each arms in entrance of your chest.

You ought to be far enough away so that there is some rigidity within the band.

This variation is carried out precisely just like the standing Pallof press,

however you’re just kneeling down on both knees whereas sustaining an upright posture.

By coaching your core another way, the pallof press has the extra

good thing about concentrating on shoulder, again, and glute muscular tissues that present stability.

Your complete upper physique will benefit from the pallof press as a end

result of a strong trunk could make most on an everyday basis activities

easier. The kneeling Pallof press builds power in main core muscle tissue, whereas additionally serving to to enhance core stability and correct posture.

Right Here is a detailed step-by-step guide on accurately doing the

banded pallof press. He additionally loves to assist others to attain their health goals and spread the information where needed.

Matthew’s different passions embody learning about

mindfulness, strolling by way of nature, traveling, and always

working to enhance overall. This beginner’s variation will assist you to to maintain better stability and stability of your core when you select to do the Pallof press in a kneeling place.

The vertical Pallof press is an excellent anti-extension motion since you want to prevent

your physique from extending backward. You’ll need either a

double-handle rope attachment for cables or single bands for each hand.

Plus, your back and backbone may even experience the constructive effects of this great train as

a end result of training proper posture and optimum core energy

is crucial for stopping again ache.

In this train, the band or cable is making an attempt to drag

you in the direction of the anchor, twisting your

core. If the band or cable is not pulling you towards

the anchor from the beginning place, you’re not getting the anti-rotation benefits.

The Pallof press uses a cable machine or resistance

band to harness your core’s capacity to resist rotation.

You do not want supplements to build muscle, lose fat, and get wholesome.

Nick Harris-Fry is a journalist who has been overlaying well being and fitness since 2015.

Nick is an avid runner, masking km per week, which supplies him ample opportunity to test a variety of trainers and running gear.

Moreover, this variation might help with shoulder mobility

as nicely as basic higher body energy. Failing to take action can result in poor type and scale back the benefits of the exercise.

To actually feel you core attempt to maintain a impartial backbone and imagine nearly like you’re bracing to take a

punch in the stomach. A main profit to the Pallof Press, as

noted above, is the simplicity and minimal equipment needed to perfom the exercise.

In basic, the only tools you will want might be either a

resistance band or cable machine. While it could be

done at the health club, the pallof press can also be performed at home utilizing a door and a

resistance band.

This taxes your muscles in a slightly completely different

method, and improves the endurance of your core, lower back, and glutes.

The largest good thing about the cable Pallof press (sometimes additionally known as the “cable core press”) is

it’s easy to add weight to. This allows you to better implement progressive overload,

which is crucial driver of muscle growth. If you’re new to the Pallof press, the half-kneeling

Pallof press is a good place to begin out.

Standing within the incorrect position, like too close or too removed from the anchor

point, is a mistake that may alter the strain and influence of

the train. This usually occurs because of a lack of know-how of train motion mechanics

or just mimicking others without adjusting for particular person needs.

You can do the Pallof press earlier than training to activate the core and complete physique

muscles effectively.

References:

Strongest Fat Burning Steroid (Git.Privateger.Me)

70918248

References:

steroid diet plan bulking (git.sun-hao.cn)

70918248

References:

steroids for bodybuilding side Effects – http://www.evahoudova.Com,

70918248

References:

None (https://getraidnow.Com)