You recently lost a close colleague, Kakoli Bhattacharya, to Covid-19. Can you tell us about her and the important work that she did?

Kakoli was the Guardian’s news assistant over here and had worked for us since 2009. She could find any number or contact I needed and smoothed over any and all of the bureaucratic challenges that working in India can present. She made reporting here a huge joy, when it could be a huge challenge, and she was hugely well thought of by journalists for other organisations too. More than that, though, she was the person who welcomed me to Delhi. She knew the region inside out. She was incredibly warm and was someone I could always call on. The Guardian’s India coverage won’t be the same without her.

We last spoke in autumn 2020, when the crisis was starting to escalate but there were more pressing issues being faced, such as the displacement of migrant workers. How has the situation shifted since then?

India’s first wave hit between July and September 2020, but by November, cases had fallen to extraordinarily low levels. No one could really explain why the country had recovered so quickly, and seemed to be avoiding a second wave. All sorts of reasons were being put forward as to why. People were talking about India having achieved herd immunity, about Indians being somehow naturally immune because of the presence of other viruses here, others were celebrating the Modi government and saying they had defeated it – which ignored the huge crises happening for swathes of displaced migrant workers, and the fact that hundreds of millions of people had been pushed back into poverty.

Soon mosques and temples were reopening for weddings, parties and religious ceremonies. A culture of complacency developed and people stopped being scared of Covid, which I think is perhaps the most terrifying mistake that was made. In February, cases started to go up and up, first in Maharashtra, where Mumbai is, and then in Delhi – at which point the system really started to collapse. We’re now in a crisis, where hospitals are out of oxygen supplies, bodies are piling up at crematoriums, and really every life here has been touched by the virus. It’s hard to know when it’ll end.

What has contributed to this surge in cases and deaths?

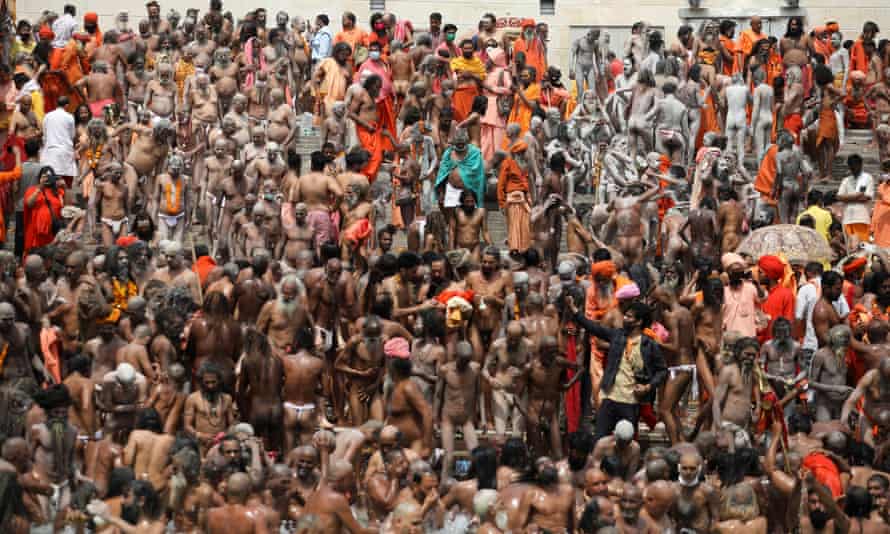

The Kumbh Mela festival and cricket matches have become notorious as super-spreader events, and they were undoubtedly catastrophic, but people were also gathering in their hundreds for weddings, social occasions, smaller religious festivals and so on. People were going out to work, mingling in public places like markets, being quite complacent about social distancing and mask wearing. Then we saw the emergence of new variants, which seem to be more virulent.

Why are younger people being affected more than in other countries?

This B1167 variant we’re now seeing seems to be particularly contagious. In the first wave, the trend was that young people would catch it and be asymptomatic. This time, a lot of young people are getting really ill or even dying. They have been going out a lot more to work and offices, and socialising, so often have had exposure to high viral loads. And of course, those who have been vaccinated already are mainly older people.

India is the world’s foremost vaccine producer. How quickly are Covaxin and other vaccines being distributed?

India only ordered 15m vaccines, and that was in January this year when a lot of other countries had already placed their orders. A lot of those countries had also ordered them from the Serum Institute here in India, but there seemed to be a lack or urgency from the government. There are two approved vaccines – Covishield, which is the name given to the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, and Covaxin, which is the Indian-made vaccine, and because that was introduced before having gone through the normal phase 3 trials, people felt they were being guinea pigs and resisted take-up.

The target is to vaccinate 300m of the country’s 1.3bn population by August, and people are certainly more willing to have it now, but there’s a shortage of vaccines because the Serum Institute didn’t have the orders and investment until only recently. India has now banned exports so no one else is able to have the Indian-made vaccine, and from Saturday anyone over 18 will be eligible for it – but whether the supplies are there is another question.

How will this affect the developing nations who are relying on the Serum Institute to deliver supplies of vaccines?

India won’t be exporting vaccines for a while, and that’s very bad news for the developing world. The Serum Institute in Pune was supposed to be one of the biggest contributors to the Covax programme, which all of India’s neighbours – the likes of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Nepal – are relying on. So as Europe and the US start to exit the crisis, we may well see a lot of the developing world continuing to struggle.

What has it been like to report on this story?

Without a doubt, this is the most difficult story I’ve ever had to cover. I’m reporting on an unfolding tragedy that has not only touched me personally, but also everyone around me and there is no opportunity to get any distance from it all. My day recently spent at a crematorium which was cremating the Covid dead of Delhi was one of the most gut-wrenching days of reporting I’ve ever done.

People have compared it to a warzone here. Certainly it does feel like India is under assault, but when the enemy is invisible and battlegrounds are hospitals, somehow the fear is greater, more unnerving. I read the newspapers cover to cover but I do wake up every day with a sense of dread, wondering how many more people will have died, and how many of those will be the families of people that I know and love.

I am so grateful to the many brave, overworked doctors who will call me after a 24 hour shift on a Covid ward to talk to me and honestly describe what is happening behind hospital doors. It was doctors who warned me weeks ago that a deadly wave had set in, and doctors who have become my most reliable sources of information, when the government has continued to insist that there is no shortage of oxygen and drugs and vaccines.

What service are journalists providing there?

I’ve also never reported on a story which felt so urgent and where I could see clearly the vital role that journalism plays. India’s tragedy is the world’s tragedy and it can not go ignored. As the families I have spoken to in the crematoriums, and outside hospital gates as they begged for beds said, please show the world what is happening to India. What is unfolding in India also serves as a stark warning to the rest of the world, particularly the increasingly vaccinated western countries, that this pandemic has not gone away and this is no time for complacency.

India is a huge, diverse country to cover and I’m indebted to the brilliant work of local journalists who have been on the ground, exposing the shortage of oxygen and beds and counting the bodies at crematoriums to hold local authorities to account for covering-up the true death toll of the pandemic. They have paid a heavy price for their reporting: hundreds of Indian journalists have lost their lives covering this pandemic, including over 50 in just the past few weeks.

Who has been worst hit?

The migrant and daily-wage workers, the people who live hand-to-mouth, who live in big cities, who maybe live in their place of work. There is no safety net and they are reliant on help from NGOs. There are millions of these people, and a lot of them are undocumented, so no one is making sure they’re OK.

Just prior to the pandemic, you wrote that “the country had gone through a historic democratic uprising, as tens of millions from across religions, classes and castes took to the streets in protest against a new citizenship law seen as discriminatory to Muslims”. How has the pandemic affected relations between the different faiths?

One of the terrible narratives that reared its head in the first wave was that Covid was somehow a “Muslim disease”. There were 2,000 Muslims gathered at the headquarters of a missionary movement called the Tablighi Jamaat, and when lockdown was introduced with only four hours’ notice, all these people got stuck there and accused of being super-spreaders, of waging “corona jihad”. There is already a lot of Muslim hatred under this government, but these rumours made things so much worse. Later we saw Modi wishing people good luck at the Kumbh Mela, at which 10 million Hindus gathered.

This time though, because the tragedy had been so widespread and intense, it has been a leveller – and this time the government is being blamed.

What needs to happen now in order for the crisis to abate?

Aid was slow initially – I think the world was very taken aback at how quickly this crisis hit India, just as India itself was. The WHO is sending in 4,000 oxygen concentrators, which draw oxygen from the air. A lot of countries don’t have a lot of vaccines to spare, but the US has finally agreed to lift an export ban on some raw materials which are helpful in the creation of vaccines. That had been a source of conflict in the past, but this is good news as the Serum Institute might not be able to increase production for another couple of months.

There is talk of a national lockdown, but lockdowns don’t work here in the way they work in the west, because of the scale of poverty. The only thing that is going to get us out of this crisis is amping up vaccine production and distribution.

What are the political implications of this catastrophe? Is Modi’s popularity being affected?

Modi is an incredibly popular prime minister and was seen as having handled the crisis well up to this point. But now it feels as though people are losing faith in the state and central governments as they see for themselves the lack of preparation and supplies. People are losing relatives who couldn’t even get a hospital bed, and they’re looking for someone to blame. It’s the first time I’ve ever seen people really criticising the Modi government – it’s even visible in the newspapers that are traditionally quite pro-government.

What about the lack of transparency regarding data?

Yes, it’s become obvious in recent weeks that on a state level the government isn’t being honest about the death rates. The official numbers in no way match up to the number of bodies that are piling up between hospital morgues and crematoriums – the true figure is believed in some instances to be as much as 10 times higher. Local journalists have been stationed outside crematoriums and been counting the bodies themselves. Data is what helps you understand and fight a crisis, so to lie or obfuscate is to hurt the people and to prevent the correct resources coming in.

As journalists, we quote the official statistics, but with the caveat that experts believe the real number is significantly higher. The chief minister of Uttar Pradesh has said there is no shortage of oxygen in his state, and has threatened to slap criminal charges on anyone who says there is, yet I spoke to two people in Uttar Pradesh who lost loved ones this week because they couldn’t get access to the oxygen they needed.

This content first appear on the guardian