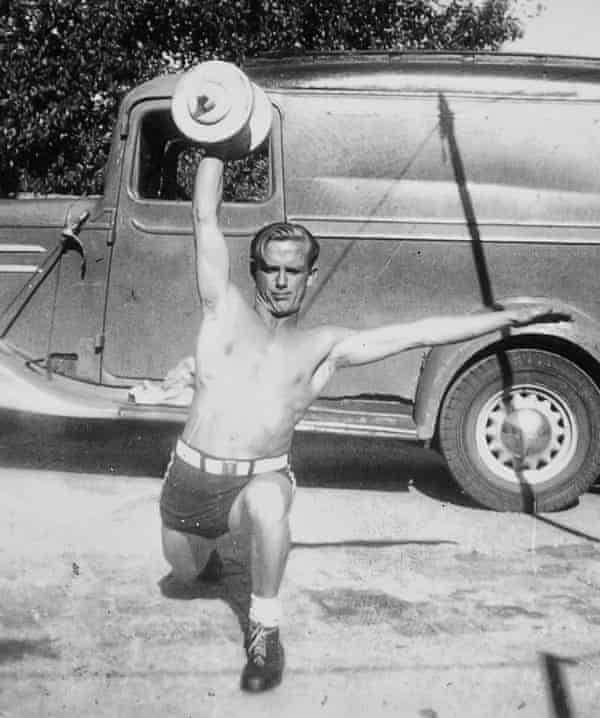

Grandad and I used to catch up every few months or so. Back then, we both lived in the same city, and I would ride my bicycle to his facility before catching a cab with him to the local pub. Over a hearty meal (always his shout) Grandad would update me on what vegetables were ripe in his garden, how he’d spent time with my mum, and his beloved trips to the gym. He was a champion weightlifter in the early 1950s. We would talk often about using exercise to help us feel balanced when life gets rough. Talking about exercise together is something we’ve done for most of my life.

When Mum called me to organise our visit with Grandad at his aged care facility, the stakes were high, much higher than having a chinwag about silverbeet or bicep curls. The pandemic restrictions had eased, allowing me to make the long, interstate drive to see Grandad. At 95, he wasn’t just struggling with the loneliness of social distancing measures. He only narrowly survived two heart failures in the middle of 2020. During lockdown I saw him just once: on a laptop screen during a zoom video call. We were only able to speak a few minutes. Once the call ended, I worried I would never see Grandad again.

Much later, offline, and with masks on, Mum and I entered his airy, light-filled room, and when I saw him I cried. Grandad looked like he’d been in a fight. There were wounds and bruises across much of his face, partially the result of a treatment for skin cancers that could not be removed surgically. He decided that another operation to remove the cancers was too risky, especially after the heart attacks. Nevertheless, his voice was calm and clear.

“It’s good to see you, mate,” he said, as I wiped away tears. “Just to know that I’ve got some of my family together, that means a lot to me.”

I suspect I am not alone in discovering more of the hardship facing many elderly Australians during the pandemic. As the royal commission into aged care quality and safety as well as past research have found, not enough funding for the aged care system and a lack of capacity to support an ageing population have, sadly, led to much avoidable pain and suffering. The neglect and abuse suffered by some elderly people in Australia’s aged care system has been awful. And the pandemic only made it worse.

My grandad has fared relatively well while growing older. For the most part, strong support from staff in aged care and his doctors and other health professionals have helped. Mum and the rest of my family have been tireless in helping Grandad too, with his garden, his exercise and just being there to talk.

Yet Grandad’s life is forever changed since his heart attacks. That exercise we talked about is mostly gone; lifting weights now impossible. He is mostly confined to his bed and chair. Without help on a daily basis, Grandad won’t survive.

James Joyce wrote in Ulysses about the many different experiences of dying and death, and how rituals are manipulated by powerful institutions, which reminds me of aged care funding today. Joyce also wrote about the “ordinariness” of death:

Therefore, everyman, look to that last end that is thy death and the dust that gripeth on every man that is born of woman for as he came naked forth from his mother’s womb so naked shall he wend him at the last for to go as he came.

Witnessing my grandfather’s frail body, and being able to talk with him, I felt the everyday intimacy of mortality for perhaps the first time. I didn’t find that mortality ordinary, however. I was shocked. I knew Grandad was sick, but it wasn’t until my visit that his struggles, and the sheer effort it took others to keep him alive, hit me with their full force. Since seeing him, the separation between his daily life and mine, demarcated by the routines of work, friends and family, has lessened. But I’ve found it hard to reconcile my visit to Grandad with what I remember of him, and what he has yet to face.

Clearly, improving the quality of life for people in aged care will require major investments in, and changes to, the sector. Those who are elderly and without strong financial, social and health support will need the most from these reforms.

Curiously, as I parted ways with Grandad, he was much more upbeat than me. Illness has not dented his passion for family, or his love of exercise, even with such severe limitations on his body.

“I can only do so many exercises now,” he told me, and then pointed to the small exercise bike in the corner of his room. “But I get on my bike for a little while, maybe only for five minutes. If I don’t do it, how good am I going to be?” If anything, Grandad’s zest for life now seems stronger than ever.

I hope Grandad’s resilience rubs off on me. And the patience and persistence of my mum and the rest of my family. I know Grandad’s future is uncertain. But, slowly, I’m feeling more comfortable with that uncertainty, knowing the certainty of his love for me, and my love for him.

This content first appear on the guardian