Australia’s vaccine rollout was dealt a blow on Thursday when the government announced that the Pfizer vaccine should be preferred for those under 50 due to concerns about extremely rare blood clotting events associated with the AstraZeneca product, which forms the backbone of Australia’s vaccine strategy.

That news led the opposition to again focus on the government’s failure to spread the risk by securing deals with other vaccine manufacturers such as Moderna and Johnson & Johnson. But even before the rumblings over the AstraZeneca clotting events translated into official advice to limit the vaccine’s distribution, the government was under pressure to explain why the vaccine rollout had fallen so far behind its initial rosy predictions.

The government has blamed the delays on supply issues in Europe that are “outside of Australia’s control”, as it remains in a dispute with the European Union over export approvals.

But until recent weeks messaging from ministers had been at pains to play down the significance of the European supply issues.

Here is how the rhetoric has changed as the rollout strategy has gradually unravelled.

September

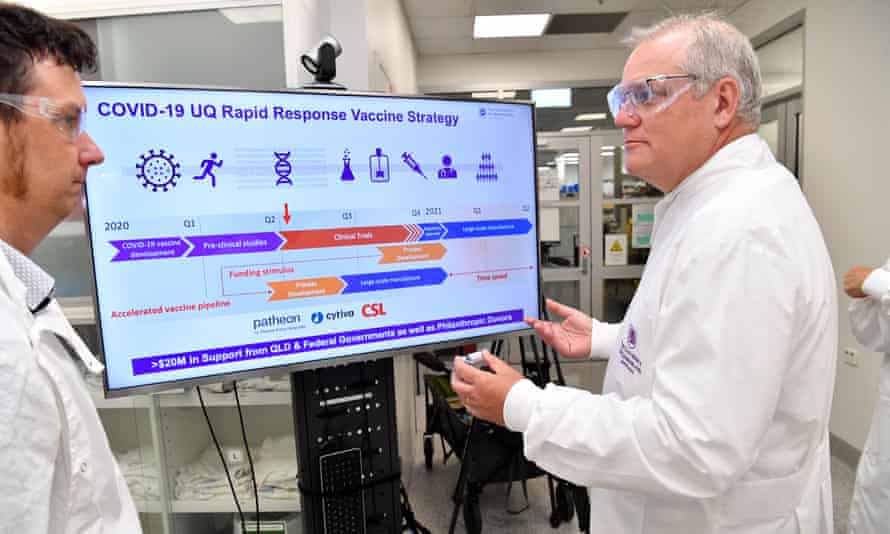

7 September: Scott Morrison announces Australia’s first vaccine deals, before any Covid-19 vaccines had finished final-stage testing or had been approved for use.

Morrison said Australia would buy 33.8m doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, which was still being developed at Oxford University. He said 3.8m would be imported, as early as January, with the remainder to be manufactured by CSL in Melbourne.

This announcement also included an intention to purchase 51m doses of the formula being developed at the University of Queensland. Both deals were contingent on the formulas passing trials.

Australia would also gain access to 25.5m doses of a successful vaccine candidate through the Covax facility – a global initiative to support research, development and production of vaccines.

November

5 November: The government announces it will purchase a further 50m doses of two other vaccines, contingent on their formulas being proved safe and effective – 40m from Novavax and 10m doses from Pfizer.

Morrison says: “We aren’t putting all our eggs in one basket and we will continue to pursue further vaccines should our medical experts recommend them.”

December

2 December: The British regulator rules the the Pfizer vaccine is safe for use, and by 8 December, the UK administers the first post-trial dose of the Pfizer vaccine in the world.

11 December: The UQ trials are abandoned after participants returned false positive test results for HIV, and the government terminates its agreement for the 51m doses it had ordered.

As a result, Australia plans to increase its reliance on the AstraZeneca vaccine, from 33.8m to 53.8m doses, with the extra 20m to be locally produced. It also announces an extra 11 million doses of the Novavax vaccine.

With purchase agreements in place for 140m doses, health minister Greg Hunt says Australia is “in a strong position”.

“This is one of the highest ratios of vaccine purchases and availability to population in the world,” Hunt says.

No specific dates are set for Australia’s first vaccinations, but the government indicates they will begin in March.

28 December: Hunt says the vaccine rollout is running ahead of schedule, and will be completed by the end of October, as opposed to the previous target of the end of 2021. He reiterates that the jab will be voluntary.

30 December: Britain’s regulator approves the AstraZeneca vaccine for use. Australian health authorities had defended the slower regulatory approvals process of the Therapeutic Goods Administration, noting foreign governments were granting emergency approvals as they were faced with escalating outbreaks.

January

4 January: The first AstraZeneca vaccine is administered in the UK.

5 January: Asked on 3AW radio why Australia’s approvals process and rollout is so much slower, Morrison says: “Australia is not in an emergency situation like the United Kingdom, so we don’t have to cut corners.

“We don’t have to take unnecessary risks.”

6 January: After sustained calls from Labor to accelerate approvals, Hunt suggests Australia will bring forward the first vaccinations from late March to early March.

7 January: The government unveils its comprehensive phased plan for the rollout, which includes starting vaccinations even earlier, in mid-to-late February.

The rollout plan includes targets of administering 4m doses by the end of March, as well as an aim to have the Pfizer vaccine approved by the TGA by late January, and AstraZeneca by February.

22 January: Morrison first mentions that international demand and supply issues from vaccine producers could delay Australia’s rollout.

“These things you know are very conditional upon the supply arrangements coming out of Pfizer in particular. As you know though, we took the decision to manufacture the AstraZeneca vaccine here in Australia so we’d be less hostage to those international supply arrangements. So that is very dependent on those arrangements. And I know there’s a lot of pressure on that group at the moment,” he tells 4BC radio.

“I was speaking to a lot of European leaders at the start of this week, and there’s been some pressure on the supplies there. So look, we’ve just got to work with that.”

At a national cabinet meeting later that day, Morrison is unable to tell state and territory leaders how many Pfizer vaccines will be received by mid-February.

25 January: The TGA approves the Pfizer vaccine for use in Australia. At a press conference, Morrison says: “No … vaccines destined for Australia have been diverted anywhere else – let me be clear about that.”

26 January: The European Union threatens to block exports of Covid-19 vaccines to countries outside the bloc, after AstraZeneca is accused of failing to give a satisfactory explanation for a huge shortfall of promised doses to member states.

The Morrison government said it still expected the AstraZeneca vaccine to be rolled out in March and that the threat wouldn’t lead to any shortfalls.

On 29 January, the European Commission agreed to an export control plan, which requires vaccine manufacturers to request export authorisation in the EU country where the vaccine was produced. Under the plan, the EC must approve each export.

By this point, AstraZeneca had advised the Australian government that it could deliver 500,000 of the vaccine doses in February and 700,000 in March.

Greg Hunt said the government would approach the World Health Organization and the EU to ensure its supply.

28 January: CSL executives decline to appear before the parliamentary Covid committee, saying the company is not available because it is “currently fully focussed on the accelerated manufacture” of the AstraZeneca vaccine. It says it hopes to provide 1m vaccine doses a week by late March.

February

4 February: Australia secures an additional 10m doses of the Pfizer vaccine, taking the country’s total order to 20m.

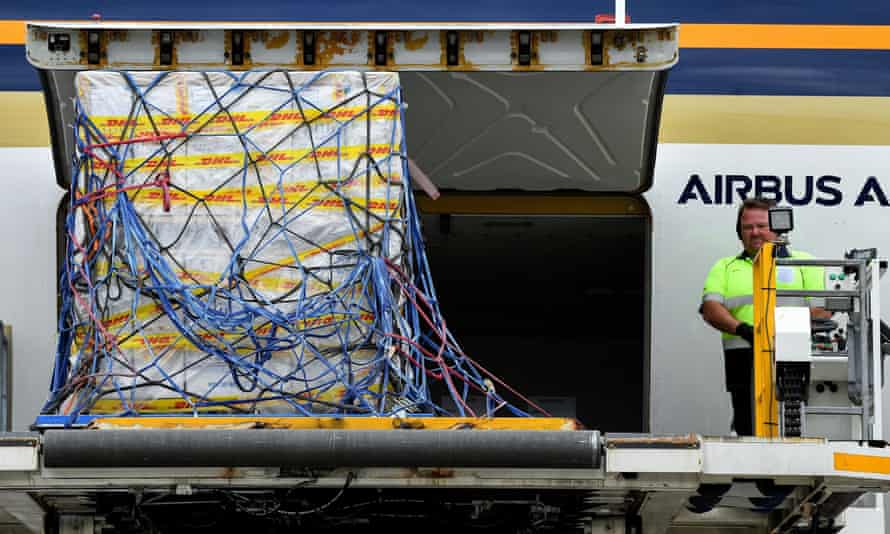

15 February: The first shipment of Pfizer vaccine arrives in Australia.

16 February: The TGA approves the AstraZeneca vaccine for use in Australia.

21 February: Australia administers its first Pfizer dose, with Scott Morrison also receiving his jab in front of media.

28 February: 300,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine land in Sydney. Later reports suggest this order came from the UK, not from the EU. After the initial shipment, AstraZeneca applies to the EU to export a further 500,000 doses from Italy to Australia, Morrison says.

March

3 March: The EU advises AstraZeneca to resubmit its application and ask for only 250,000 doses, a temporary reduction that Morrison agrees to.

5 March: As Australia’s first AstraZeneca vaccine is administered, the government learns that the EU has blocked the export request for the reduced order of 250,000 doses. Hunt asks for the decision to be reviewed.

Seeking to quash concerns about the impact of the decision, Morrison says: “This particular shipment was not one we’d counted on for the rollout, and so we will continue unabated.”

Hunt goes further, suggesting Australia does not need more than the 300,000 AstraZeneca doses it has already received to continue its rollout without delay.

Sign up to receive the top stories from Guardian Australia every morning

Sign up to receive the top stories from Guardian Australia every morning

“We are very clear that this does not affect the pace of the rollout. That shipment had not been factored in to our distribution to the states and territories. And in fact we received the first shipment of AstraZeneca this week of 300,000 doses,” Hunt says.

“So, we had planned the AstraZeneca rollout based solely on those 300,000 doses that had arrived in Australia, and we were very, very cautious on that front, and so there are more than enough to see that bridge through to the arrival of the Australian-made CSL AstraZeneca doses.”

The government later says the EU by now had signalled the same supply issues would lead it to block further export requests.

11 March: The government walks away from its promise to fully vaccinate all Australians by October.

19 March: Morrison pleads with the EU to redirect 1m of the doses Australia had ordered to Papua New Guinea – which is grappling with its coronavirus outbreak – as the EU’s export control excludes vaccines destined for low and middle income countries.

22 March: CSL completes production of its first batch of AstraZeneca vaccines.

By the end of March, Australia has administered nearly 600,000 doses, 3.4m short of its target for the end of the month, as local doctors who joined the rollout complain of a lack of supply and organisation.

Hunt asks AstraZeneca to resubmit an export application to the European Union.

April

6 April: Facing questions about the delays in the rollout, Morrison says the situation in Europe has “frustrated” supply and caused delays.

“The supply is the major restraint and always has been, whether it’s been the non-delivery of vaccines from overseas, some three million that we were relying upon …They’re circumstances that are outside Australia’s control,” he says.

This marks a shift from Hunt’s remarks on 5 March that Australia did not require more than the 300,000 foreign AstraZeneca doses it had already received.

The EU hits back at Morrison for suggesting it had blocked all 3.1m doses not yet delivered, pointing out it had only blocked one shipment. The government then accuses the EU of “arguing semantics”, noting the body had signalled it would not approve further exports, so it had not asked AstraZeneca to submit requests.

Morrison renews calls for the EU to allow the outstanding doses to be shipped to Australia, including a pledge to give 1m to PNG.

7 April: CSL has still not reached its million dose per week production target set by the government.

As of 7 April, 1.3m doses have been released from CSL, while the number of imported AstraZeneca doses remains at 717,000. Australia has received 870,000 doses of the Pfizer vaccine from overseas. About 920,000 vaccine doses have been administered.

Hunt says he expects 1.62m doses to be produced by CSL and cleared for distribution by “early” in the week beginning 19 April.

8 April: In a hastily-called evening press conference, it is announced that under-50s should be given the Pfizer vaccine in preference to AstraZeneca as a result of the rare blood-clotting cases.

The advice from the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation says: “Until the government can increase supply of Covid-19 vaccines other than AstraZeneca, overall coverage under Australia’s Covid-19 vaccine program will likely be reduced. This will likely impact the time frame to which the Australian population is protected against Covid-19.”

9 April: Following a national cabinet meeting, Morrison announces Australia has secured a further 20m doses of the Pfizer vaccine taking the total to 40m. The newly ordered doses are expected to be available in the final quarter of 2021.

Morrison acknowledges Australia’s vaccine rollout will likely push into 2022. Asked if he could guarantee all Australians would receive at least their first dose of a vaccine by Christmas, Morrison says “we’re not in a position at the moment to reconfirm a timetable”.

The opposition health spokesman, Mark Butler, offers this assessment: “Frankly, this government put too many of their eggs in a single basket and now we are paying the price.”

This content first appear on the guardian