I’d like to tell you about a man called Chris. In his early 40s, Chris has spent years holding down low-paid jobs, all while caring for his elderly mother. Chris has autism, a mild learning disability and a stammer. And, as is the case with many people in his situation, employers tend not to want to give him a chance. Over the past year, he has been furloughed from his part-time cleaning job; he is given a few hundred pounds a month to somehow pay the bills. Disability benefits helped to keep his head above water. That was until a new assessment last year took them away.

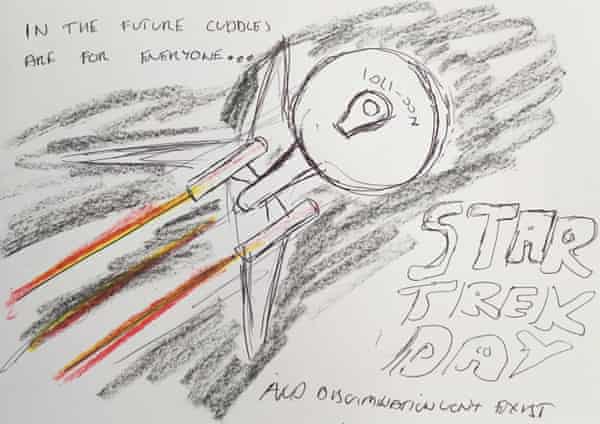

Last month, Chris appealed against the decision at a “phone call” tribunal. Lockdown has stopped in-person court dates but benefit cuts carry on. Sat in his mother’s house, with a pile of paperwork, he was turned down again. Now, Chris relies on food packages from local aid groups; pasta and veg in a cardboard box. “Having to receive food parcels is the most humiliating experience of your life,” he says. “You don’t forget.” Chris adores Star Trek and likes to draw pictures of the stars and space, his crayons sketching the possibility of a kinder world. Mostly, he says, he just wants a hug.

This is not a remarkable story. It happens every day, in every corner of this country, a kind of normalised neglect that is permitted to spread silently. The pandemic is said to have turned the spotlight on Britain’s social security system, but the truth is millions of people like Chris are still living in the dark. A decade of austerity has stripped £37bn from benefits support, as a mixture of squeezed rates and Kafkaesque tests built a system more interested in punishment than help.

Coronavirus has only served to weaken a society already infected by poverty. Research by the charity Turn2Us shows one in five people are now struggling to pay the bills, and one in six to afford food. Ministers appear to have neither the skill nor the will to meet the demands of our times. Their idea of a “generous” benefits system is giving some of the poorest people in society an extra £20 for a few months. For disabled and severely ill people on legacy benefits, April will see a rise of the grand sum of a 37p a week. That’s barely half a loaf of bread to cope with a global pandemic.

The paradox of the narrative that Britain’s bloated benefits bill is out of control is that, by any definition, it is uniquely miserly. The UK has the lowest unemployment benefit as a share of previous income in the OECD. The majority of disabled people who are unable to work say they can’t afford to live on what the state gives them. Even with the £20 increase, many universal credit claimants are still having to skip meals.

This month, Britain’s leading expert on health inequalities, Sir Michael Marmot, warned that the welfare system must be overhauled after the pandemic, and few looking at the evidence would disagree. And yet it is surely bleak that it took a pandemic to trigger such concern. There is no reason to wait for decency, no compassionate future held hostage to the right conditions. The time is now, and the truth is, it has been for many years.

The destruction of Britain’s safety net has been a public policy crisis for decades, yet we are still arguing for the most basic aims: that social security should be enough for people to be able to eat regular meals, keep the electric on, and pay the rent.

It is not “generous” to stop people from starving. It is the absolute bare minimum we should do as a society. That we have convinced ourselves otherwise says much about the attitudes that require challenge, just as the fact that any emergency rise was needed during the pandemic betrays how little we’ve expected people on benefits to live on.

Similarly, the idea that nobody should work all day and still live in poverty dominates progressive arguments. It’s entirely true, but it is a framing that in itself capitulates to the terms of the right. Nobody should live in poverty full stop; the completion of work should not be a precursor for a society to treat someone as a human being. Unpaid carers who have propped up the care system throughout the pandemic should surely teach us that.

It would be natural to feel disheartened at the way things are. The scale of suffering is steep, and the political class seems uniquely ill-equipped to climb it. But carrying on blindly is hardly an option. As the end of lockdown brings the so-called return to normal, we may actually realise that what many people need is change. Where society puts its resources is a symbol of what it thinks matters, and we can choose to invest in social housing, a real living wage, increased benefits or basic income. There will be many hurdles facing us in the coming months but the scale of our ambition should not be one of them.

Look to the stars and imagine a better world. Then come back to earth and fight for it.

This content first appear on the guardian