Like so many on Brazil’s left, Pedro Carvalho was certain Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency would prove a nightmare: for human rights, for the environment and for the national health system the 41-year-old doctor cherishes and serves.

“I felt this profound sadness, just utter, personal sadness,” Carvalho remembered of the fateful moment in October 2018 that the far-right populist was confirmed as his country’s new leader.

“He’d been a politician for 30 years. Everyone knew who he was,” the intensive care physician said of the dictatorship-praising former paratrooper. “He is hatred. He is hatred itself.”

Back then, of course, nobody knew Brazil was also barreling towards its most devastating public health catastrophe since the Spanish flu, or that Bolsonaro would so ruinously mishandle an epidemic that has now killed more than 300,000 of his citizens, his wife’s grandmother included.

“We thought perhaps he might delegate the response to a health minister and leave them to it … while he sat around making gun signs with his hands,” Carvalho said of Brazil’s pro-gun president.

He was mistaken. From the start of Brazil’s Covid epidemic last February, Bolsonaro busied himself trivializing its dangers, shunning face masks, sabotaging social distancing and urging citizens to reject lockdown. In less than a year he has forced three health ministers from power, two for questioning his championing of bogus treatments such as the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine.

The consequences, say critics, have been deadly. On 24 March 2020, with Brazil’s Covid death toll at 46, Bolsonaro claimed the pandemic was being exaggerated “and soon it will pass”. On Wednesday, exactly a year later, the number of fatalities surpassed 300,000 after a record 3,000 lives were lost for the first time in a single day. Only the US, governed until January by Bolsonaro’s rightwing inspiration, Donald Trump, has suffered greater losses, with scant sign of Brazil’s outbreak being brought under control.

“We are adrift,” said Carvalho, who has a front-row seat to the tragedy at his ICU in the north-eastern state of Pernambuco, where all beds are now full. “What we are witnessing is the politics of death.”

Carvalho said he felt a mix of dejection and disgust as he reflected on Bolsonaro’s role in a calamity now steaming into its deadliest phase because of a months-long collapse of containment measures and the more contagious P1 variant linked to the Brazilian Amazon.

“I don’t expect things to improve, not for now at least,” he said, pointing to the country’s faltering vaccination efforts. “As a health professional, I wish … I could tell people: ‘Hang on people, we’ll get through this.’ But I just don’t see it. I can’t offer people words of encouragement any more.”

Carvalho is not alone in his pessimism, with some Brazilians so crestfallen they have begun draping black cloths from their windows to mourn victims and demand Bolsonaro’s impeachment.

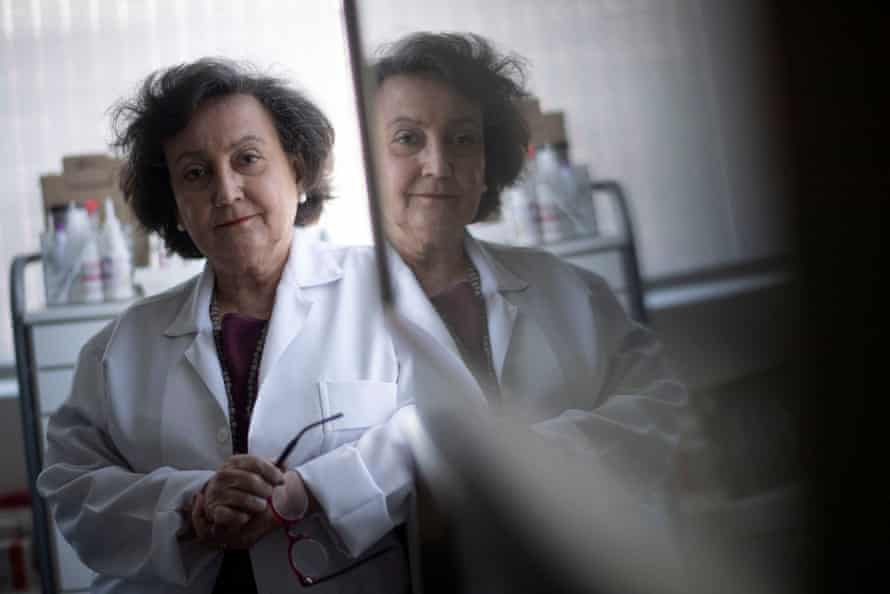

“We are having the saddest March of our lives,” said Margareth Dalcolmo, a Rio-based professor whose straight-talking Covid media appearances have made her a South American equivalent to England’s chief medical officer, Chris Whitty.

Dalcolmo, a sparkly 65-year-old pulmonologist, said she made a daily effort to remain positive despite the deepening gloom. “There’s a Brazilian author called Guimarães Rosa and he wrote the most beautiful thing: ‘Such is life: it becomes warm and then cools, it tightens then loosens, it settles and then jolts. What it asks of us is courage.’”

But after 13 months in which she had lost patients and friends, and fallen ill herself, staying upbeat was a challenge. “I used to joke that we’ll finish this epidemic with more scars than skin,” she said, remembering one friend, a celebrated surgeon called Ricardo Cruz, who died in December. “He was wonderful human being, a wonderful doctor, a very dear friend,” Dalcolmo said. “The price in human life, the mourning, is something that will never be recovered – never.”

Dalcolmo said Brazil should have been well positioned to counter Covid, thanks to its NHS-inspired health service, SUS, the largest in the world, and an immunisation programme capable of delivering over a million shots a day. But the government failed to buy sufficient vaccines and bamboozled the population by denying science and pushing unproven remedies. The future looked bleak. When historians look back on Brazil’s epidemic, “they will write a sad story”, Dalcolmo predicted, “and even with some components, I would say, of villainy, you know?”

With polls suggesting mounting public anger, Bolsonaro sought to strike a conciliatory tone this week, announcing the creation of a coronavirus committee more than a year after the epidemic began. In a televised address Bolsonaro claimed his administration had fought “tirelessly” against Covid and to avoid “economic chaos” and was committed to a vaccination campaign he has repeatedly undermined.

That intervention sparked pot-banging protests and cries of “murderer!” across Brazil, including in the riverside city of Petrolina, where Carvalho is battling to save lives. The doctor could not join the jeering after a raging fever and throat infection forced him to abandon the frontline on Sunday after intubating an elderly woman close to cardiac arrest. But Carvalho watched Bolsonaro’s proclamation from his sick bed and, like many Brazilians, was unconvinced and incensed. “Just one lie after the other,” he scoffed of the claim normality would soon return.

Despite their bearing the brunt of Brazil’s failure, Carvalho was convinced his SUS colleagues would keep fighting, insisting: “We won’t step back. We won’t give up.”

But he felt physically and emotionally shattered and looked to Colombian literature to describe the psychological toll of being at the eye of this Brazilian storm. “Tú no sabes lo que pesa un muerto,” he said, quoting Gabriel García Márquez. “You can’t imagine how much a dead man weighs.”

This content first appear on the guardian