In the disUnited Kingdom there are glimmers of light for the theatre. Some openings are scheduled for 17 May; with further relaxation of restrictions, more are likely to follow in June. The support in Rishi Sunak’s budget, which announced an additional £300m for the culture recovery fund, is welcome. Still, there are painful gaps. Some had hoped for a government-backed insurance scheme, and for an increase to the rate of theatre tax relief. Neither were forthcoming. Crucially, while the government bailout has secured the future of vital institutions, the livelihood of large numbers of theatre-makers – actors, designers, stage managers, musicians and others – is still in jeopardy.

In the interviews below, I am intrigued by Ivan van Hove’s jealousy of Boris Johnson’s “generous” speech about the arts. I would rather have the Dutch prompt delivery of cash – less ho ho and more dough – and sadly thunderstruck by Kajsa Giertz’s calm assumption that in Sweden the theatre is “a part of democracy” that must be affordable to everyone. In contrast, the vocabulary in which the UK discusses the arts often reeks of hierarchy and materialism. Oliver Dowden talks of saving culture’s “crown jewels”: what happens to the plebby bits?

I am also struck by arrangements in France and Germany: by Stéphane Braunschweig’s description of their unemployment system, which ensures some stability for theatre workers, and by Thomas Ostermeier’s account of furlough for permanent company members. Things are different in this island. On an average UK production, 80% of theatre workers are freelance. Though the budget expanded the number of those entitled to the self-employment income support scheme, some 65,000 are still not eligible. In our national obsession with bricks and mortar we are in danger of forgetting that the theatre is aided but not made by buildings. Support for freelancers must become a priority.

There is room for private initiatives. Let sponsors of the arts look to attaching their names not only to new auditoria or theatre bars but to up and coming talent. Why not set up post-pandemic scholarships, for actors, directors, designers and technicians at drama schools throughout the country to help stop them becoming the preserve of the wealthy? The last Labour government could have established millennial scholarships but spent the money on a dome. We now have a chance to begin putting that right, proving we are not only a nation of shopkeepers but the country of Shakespeare.

Susannah Clapp is the Observer’s theatre critic

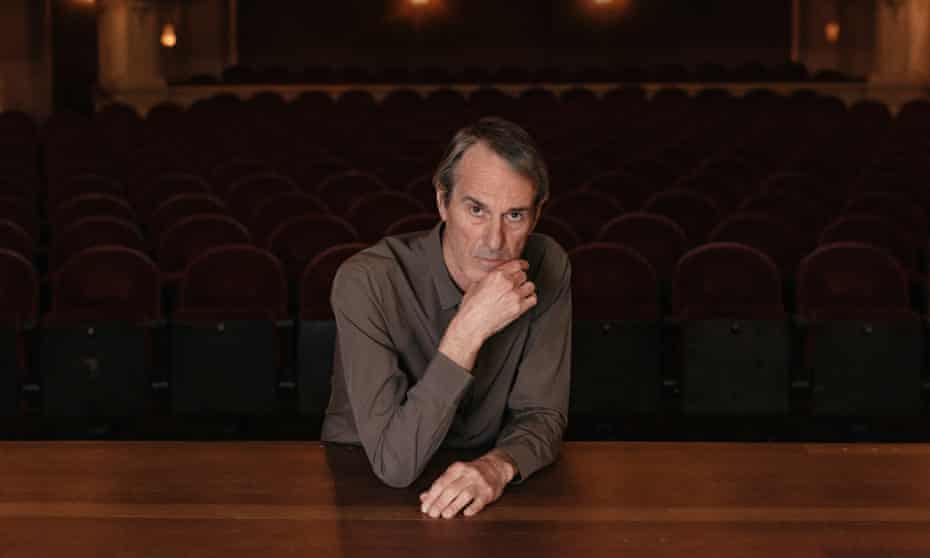

Thomas Ostermeier, artistic director, Schaubühne theatre, Berlin: ‘Livestreamed theatre is like methadone for heroin addicts’

Thomas Ostermeier has been the artistic director of Berlin’s Schaubühne theatre since 1999, in which time he has transformed the former modernist cinema on Lehniner Platz into one of the most influential stages in Europe. Often marked by the intense physicality of their performances – his 2008 Hamlet had Lars Eidinger’s Dane writhing around a stage floor covered in soil – Ostermeier’s interpretations of classic texts also seek to find concrete answers to contemporary political questions. He once described his style as “capitalist realism”. Revered in France, where Ostermeier’s ensemble are regulars at the Avignon arts festival, the Schaubühne has also become an experimental playground for British playwrights and theatre-makers, including Mark Ravenhill, Katie Mitchell and, most recently, Simon McBurney.

What has the pandemic been like for your company?

We closed our theatre the day after the first lockdown back in March last year. Even when some other theatres reopened in the summer, we stayed shut until the beginning of October, as we had pre-booked some maintenance work on our air conditioning system. That turned out to be quite handy: we now have a state-of-the-art air filter that every half hour replaces the air inside the auditorium with fresh air from the outside, and thus meets the Berlin senate’s requirements for reopening.

When do you hope to reopen, and with what?

During the summer we started rehearsing a lot of shows, including a version of Heinrich von Kleist’s Michael Kohlhaas by Simon McBurney, and a production of Yerma by Simon Stone after Federico García Lorca, but we haven’t been able to premiere them. Now we are trying to bring them on stage after Easter. The first play will probably be my adaptation of Virginie Despentes’s Vernon Subutex 1 in April.

How has your government/state supported theatre during the pandemic?

After October we only reopened two and a half weeks before the second lockdown at the beginning of November. Since then, our 240 permanent members of the company have been on the German furlough system, Kurzarbeit. In the first lockdown, the German social insurance agency paid 60% of their salaries and we made it up to 92%, or 94% for those with children. During the second lockdown, the social insurance agency has paid 80% of their income and we added another 18%. That’s an incredibly privileged and luxurious position to be in.

In Germany, the furlough money comes from a state insurance that every employee pays into. These contributions are pretty high, and there are constantly free-market voices telling us that they should be lower. But in this crisis we are profiting from the contributions we have paid to prepare for a situation like this.

The Schaubühne has a special status, in that we are both state subsidised but also a private company with four shareholders, one of whom is me. In this situation this was a big advantage, because we managed to reach an agreement on the furlough scheme with the union after just two days. Berlin’s state-owned theatres, by contrast, couldn’t put their employees on furlough for the first 10 months because they only reached an agreement in January. But the situation that a lot of British and American theatres are in is even more of a nightmare: unlike us, they can’t open their theatres with reduced seating in the way we are. They need a full house to survive.

Has there been a theatrical response to the pandemic, a digital initiative that really got people talking in your country?

Honestly, no. As far as I know there are no examples of independent theatre-makers who all of a sudden managed to reinvent performance art on a digital level. And it’s pretty obvious that that is not possible. When we work on streaming events, we put a three-dimensional art form into two dimensions. And there is a long history of doing this: it’s an art form called cinema, which is 120 years old. We are suddenly competing with that tradition. Every night when we livestream a show, we are up against Netflix and Amazon Prime. Livestreamed theatre is like methadone for heroin addicts: you don’t get the same kick as with the real thing. So it’s no surprise some people prefer to watch The Crown instead.

What’s the main thing you’ve missed about going to see live theatre?

The one thing that theatre is unrivalled at among art forms is its ability to produce art in the moment. In theatre, an actor creates the artwork in front of you in real time, and you know it has never been created in exactly the same form before and will never be created in the same form again. In a digital age, where most of our experience of the outside world is via a screen, I believe people have more and more of a craving for that kind of unmediated contact with the outside world.

What play do you think most speaks to this time we are living through?

I am currently working on a production of Oedipus. The drama is set in Thebes at the time of the plague. The gods tell Oedipus that the pandemic will end once he reveals who murdered his father. And as we all know, Oedipus himself is the origin of the plague, because he killed his own father. That is not only true of the pandemic; we are also the origin of an even bigger drama, the drama of our time: global warming.

Have any positives come out of coronavirus for you?

One positive is that we suddenly have time to reflect. There’s a famous quotation by the German dramatist Heiner Müller, who in the early 90s proposed that theatres should close for a year while the theatre-makers were still being paid, “and afterwards maybe we know why theatre is needed”.

Interview by Philip Oltermann

Ivo van Hove, artistic director, Internationaal Theater Amsterdam: ‘Every time we opened, tickets sold out within an hour’

Born in Belgium, Ivo van Hove is the artistic director of the acclaimed Internationaal Theater Amsterdam. As well as his work for ITA, he is also known for productions for theatres abroad, such as A View from the Bridge, Hedda Gabler and Network, all of which premiered in London. His Broadway production of West Side Story started previews in December 2019 and played for 200 performances before theatres closed in the US because of Covid. He lives in Amsterdam with his partner and collaborator, Jan Versweyveld.

What has the pandemic been like for your company?

We have managed to keep working in one way or another. As everything closed in March 2020, we immediately recorded 100 filmed readings from Boccaccio’s The Decameron, stories set amid a plague. When we were allowed back into the theatre, we staged three productions, including Children of Nora, a new play by Robert Icke, with socially distanced audiences. Very small, but doable. The company spirit has been good because people felt we could do fresh, meaningful work.

When do you hope to reopen and with what?

Touch wood, I will reopen for the Holland festival in June with Age of Rage, a mashup of all the Greek tragedies that tell the story of the Trojan war. It’s important because it talks about how we get into cycles of violence – how people are radicalised, why they get angry, how they are led.

How has your government supported theatre during the pandemic?

ITA is supported by central government and by the city of Amsterdam, but we make a lot of our income from international touring, which of course we have lost. The government gave two grants which will help us survive the immediate future. We’ve managed to pay our staff, technical team and ensemble of full-time actors throughout the lockdown, and we paid our freelances and kept employing them in new productions. At ITA, 70% have full employment and 30% are freelance.

Is there anything the Dutch government has done that’s been particularly successful – and what have they got wrong?

They paid out the money immediately, as soon as we needed it. I have heard in Britain that people are still waiting for payment. But it took them a long time to use the word “theatre” in a press conference. Boris Johnson gave a generous speech in which he talked about the importance of the arts. Also Chancellor Merkel and President Macron. They never said this in Holland. They give you money, but it’s not heartfelt.

What’s the main thing you’ve missed about going to see live theatre?

Being together with people and feeling what you have made moves them in some way. And the moment after a performance when you relax, and ideas pop up. The arts are a community. That’s what I really miss, but that will come back.

Is there a production or digital initiative that really got people talking?

We started ITALive and have already streamed eight productions; one of them was Shakespeare’s Roman Tragedies, which lasts more than six hours. We worked with a TV crew and director, who are used to filming rock concerts. That became a fantastic collaboration, and we got a lot of good reactions all over the world.

Is there public support to get the arts moving again?

Every time we opened, tickets sold out within an hour. People were hungry to come. They also trusted us to provide a safe environment. The streaming has been a huge success too, with 60% of the views coming from people who are new to us.

Is there anywhere you look at and think: I wish I worked there because they are handling it so much better?

When Boris Johnson spoke about theatre, I was jealous. Also in France and Germany, they have given a lot of money to support culture.

Apart from your own, what theatre in the world would you most like to go to when you are able?

For private pleasure, I go to the cinema. My dream is to go to a wonderful cinema near my home called FilmHallen. I’ll be there on the day it opens.

What play do you think most speaks to this time we are living through?

No play that I know immediately. In a year that loneliness has become part of our lives, Thoreau’s Walden, which is a work that celebrates solitude.

Interview by Sarah Crompton

Saheem Ali and Shanta Thake, associate directors, Public Theater, New York: ‘The arts will be central to helping people heal’

The off-Broadway Public Theater – producing theatre “of, by, and for all people” – was founded in 1954 as one of the US’s first non-profit theatres and has 54 Tony awards and five Pulitzer prizes to its name. Hair (1967), A Chorus Line (1975) and Hamilton (2015) all started life here before transferring to Broadway and global acclaim. In April 2020, the theatre had the first online hit of the pandemic, when the playwright Richard Nelson reconvened his celebrated Apple family for the Zoom-set play What Do We Need to Talk About?. Saheem Ali and Shanta Thake were promoted to associate artistic directors in August 2020 as part of a determined plan by artistic director Oskar Eustis to diversify the theatre’s management in response to Black Lives Matter.

What has the pandemic been like for your theatre?

Saheem Ali: I’ve directed Richard II, Anne Washburn’s Shipwrecked and now Romeo y Julieta, a bilingual adaptation of Shakespeare, as audio dramas on public radio. We’ve had a full programme of digital work, and some streamed work from [the Public’s smallest venue] Joe’s Pub.

Shanta Thake: It’s a blank slate moment. We’ve used the time to think about the core of our mission – who are the audiences we serve, and what are they asking for?

SA: A lot of institutions are asking questions about systemic racism. We are figuring out how we can be better citizens, human beings and artists on the other side of this.

When do you hope to reopen?

ST: There have been encouraging updates; New York state just announced that outdoor and indoor performances with capacity limits and other safety measures can begin in early April.

SA: And as a not-for-profit organisation we’re in a position to come back faster than Broadway. Our bottom line doesn’t depend only on ticket sales.

How have the authorities supported theatre during the pandemic?

ST: Luckily, we are part of the Cultural Institutions Group of New York and receive funding from the city. The value of culture is clear to our elected officials, and there has been a lot of attention paid. But we are very reliant on our donor base.

SA: We’ve raised money ourselves to support the infrastructure and staff, and fund the digital programme, which has all been offered free.

And what about other companies – and freelancers?

ST: The government has made some improvements, but we’ve a way to go to address the impact of [the past year]. We’ve started a freelance artist initiative at the Public and have given hundreds of $1,000 grants to freelancers who no longer have an income stream and do not qualify for federal relief. There are so many gaps in our system.

What could the authorities have done better?

SA: Last year we did not have a federal administration who took health concerns very seriously, so we lost a lot of time and a lot of momentum when we could have been more proactive. We’re lucky to be in New York, where we take reopening the arts seriously. Other parts of the country are not so fortunate.

Does the change in the White House help your cause?

SA: It certainly helps morale!

ST: We are hopeful that this administration places more emphasis on culture than the previous one.

What about initiatives coming from inside the theatre world? ST: We’re working with the Oregon Shakespeare festival and Woolly Mammoth [another non-profit theatre company] in Washington DC to help our elected officials understand what it’s like to work in live performance.

SA: We don’t have a minister of culture in this country, or a government official who is in charge of supporting the arts, so this initiative is to try to get one.

Is there public support to get the arts moving again?

ST: I think people feel the loss of live performance in myriad ways. The arts will be central to helping people heal and to grieve but also to find new hope. That won’t happen through health policy, but through gathering together in ways that are safe.

What play do you think most speaks to this time we are living through?

SA: James Ijames’s play Kill Move Paradise is about four black men who have been subject to police violence and discover they are in purgatory. There is something about the purgatorial nature of that, in terms of the racial conversation we are having in America, that is completely and sadly relevant.

ST: Toshi Reagon’s stunning opera The Parable of the Sower, an adaptation of Octavia Butler’s book about what it means to be a part of a community, to grow a new community, and to come to terms with change.

What has got you through lockdown?

ST: Apart from red wine? I’ve been reading Adrienne Maree Brown and also Octavia Butler’s novels. I’m currently reading Braiding Sweetgrass, a beautiful book about indigenous wisdom. Plus, I’ve watched Bridgerton. Obviously.

SA: I bought a DJ set and taught myself to spin, and threw a Zoom party for 20 friends!

Sarah Crompton

Stéphane Braunschweig, artistic director, Odéon-Théâtre de L’Europe, Paris: ‘It’s only when you have no theatre that you understand that it really is a necessity’

One of France’s five national theatres, the elegant neoclassical facade of Paris’s Odéon has been a Left Bank landmark since 1819. Stéphane Braunschweig headed two other French national theatres, the Théâtre National de Strasbourg and La Colline, before joining the Odéon in 2016. His richly psychological productions of Chekhov, Shakespeare, Molière, Ibsen and more have won acclaim across Europe and toured widely.

What has the pandemic been like for your theatre?

It has been a sort of nightmare. We closed, like every other theatre, last year in mid-March, then we reopened in September only to close again at the end of October. So in one year we have performed only two productions and cancelled or postponed 14.

When do you hope to reopen and with what?

I have no answer for when – nobody has an answer. But the production we hope to reopen with is from Christophe Honoré, who is a film director and also a writer for the theatre. It’s his adaptation of Le Côté de Guermantes by Marcel Proust. We have also been rehearsing my own production of Luigi Pirandello’s As You Desire Me, so that is ready to run too.

How has the government supported theatres and theatre workers through the pandemic?

We are a national theatre, so 62 per cent of our funding comes from an annual state subsidy of €12.3 million. This funds the running of the theatre itself, but to pay for productions and for freelance artists and technicians’ salaries we need the box office and the income from our shows on tour. We need sponsors, too.

In France there is an unemployment system for people working in the theatre, cinema and television – intermittents du spectacle – and it’s a very good system. I worked some years ago in England, and I can remember really good actors who were obliged to work in a bar – or nowadays it would be as a delivery driver – when they were between jobs. In France, actors get a government-funded salary when they’re out of work, as do technicians and others in the business. It helps them to retain a more permanent sense of professional identity.

Does reopening the arts feel like a government priority as well?

I think the government’s absolute priority is not to recontaminate, so they are doing everything to avoid that, which includes keeping theatres closed. So we feel we have been sacrificed in a way – but I don’t think that’s because the government doesn’t care about the arts. We can see that they do in the way they have supported artists financially, and in Roselyne Bachelot we have a minister of culture who fights very hard for her corner.

Have you noticed any really smart responses to the pandemic in the theatrical world?

The Comédie Française has created an online TV channel. It’s wonderful. They have in-house actors, so it’s a great way to take advantage of that.

Apart from your own, which theatre anywhere in the world would you most like to go to when you are able?

I would like to travel again. I’ve been every day in Paris for months and months. I need to see and hear the language of theatre across Europe. So if I could, I would go to see friends and performances in Italy, Germany and England.

What play do you think most speaks to this time we are living through?

Last September we staged Racine’s Iphigénie, and that was in many ways a response to the pandemic. In the play, the Greek army is about to go to destroy Troy. But the winds have ceased, so there is no possibility of sailing. And the central question of the play is: what would you sacrifice to create again the possibility of moving? And to me, that’s really the question of our times. Do you want to sacrifice the economy, or do you want to sacrifice human life?

Have any positives come out of this time for you professionally, or personally?

Sometimes the theatre world is very individualistic. And I think we have found again a feeling of solidarity between artists, directors and theatres. And that’s a good thing. I also think that it’s only when you have no theatre that you understand that theatre really is a necessity. I think for many people it’s the way to understand our culture and the way we live now. It’s a deep need in our world. At least now we understand that. Lisa O’Kelly

Kajsa Giertz, artistic director, Helsingborg City theatre, Sweden: ‘In Sweden, theatre tickets are not much more expensive than the cinema’

Kajsa Giertz is artistic director of Helsingborg City theatre in southern Sweden. Originally a dancer and choreographer, she has worked in dance, theatre and opera as a director, educator and playwright for more than 30 years. Helsingborg City theatre opened in 1877 and has links to some of Sweden’s greatest names: it hosted the world premiere of Ibsen’s Ghosts in 1883 and helped launch the career of Ingmar Bergman, who took over as manager, aged 26, in 1944.

What has the pandemic been like for your company?

We had the theatre open until 22 March 2020. At that time, the pandemic situation was bad in Stockholm, but here in southern Sweden it wasn’t so bad. But still, there was so much anxiety that we decided to close. After the summer, we could open again with a restriction – 50 in the audience, socially distanced. Then on 15 November the government said only eight people were allowed indoors. So all the museums, galleries and theatres closed.

When do you hope to reopen? And with what?

There is a chance that we might be able to open in the spring. If so, we will open low-key with some monologues that we can rehearse without killing one another with the virus and then we’ll see. We are actually planning to do some outdoor theatre in August, too.

How has your government supported theatre during the pandemic?

As a city theatre we are funded by a municipal grant of 70% and a state grant of 20%. We usually get 10% from ticket income. It’s the same for most regional and city theatres in Sweden, so it’s quite different from most countries. The government here really believes that the theatre should be for everyone, because it’s a part of our democracy and no one should not be able to afford to go. So tickets are not much more expensive than a cinema ticket. That’s really what makes me wake up in the morning. I think this is such an important job to do, and that everyone should have this opportunity to see the arts.

So you haven’t struggled financially?

Our economic situation is OK. We are actually getting extra state support to compensate for lost box office income. The ones I worry for are the private theatres and the freelancers… There are bodies they can apply to for support, but the process is very slow. My fear is that the freelancers will all decide to give up and do something else, because it feels so insecure to be without work for so long. I’m trying to stay in contact with the ones I usually work with – set designers, directors, lighting people – trying to set them up for future things, so they know that they have something to come back to.

What have you staged during the past year?

We premiered a play on Zoom last month that has attracted a lot of attention. It’s called Trådgårdsgatan [Garden Lane], a new drama set in the street that divides the wealthy side of Helsingborg from the less well-off part. We’d been rehearsing it on Zoom [preparing for live audiences], and when I realised that was not going to happen, the director said: “Let’s stage it on Zoom.” We’re now getting 1,000 viewers per show.

What has got you through lockdown?

In Sweden we have not had a lockdown as such, but it has been an anxious time. To help, I have been walking in nature. There’s a lot of space in Sweden and not so many living here, so it’s wonderful outside. And also, like everyone else, I am knitting.

What’s the main thing you’ve missed about going to see live theatre?

The ritual of it: going with other people, going out in the intermission, talking a little bit, then going back in. And I miss that special theatre magic, which is that what happens only happens now, in this second, just for us, and it’s not ever going to happen again. That’s such a deep delight, and I think so many people are missing it.

Lisa O’Kelly

This content first appear on the guardian