When Dr Anthony Fauci spoke at the 20th International Aids Conference in Melbourne in 2014, his appearance garnered little media attention.

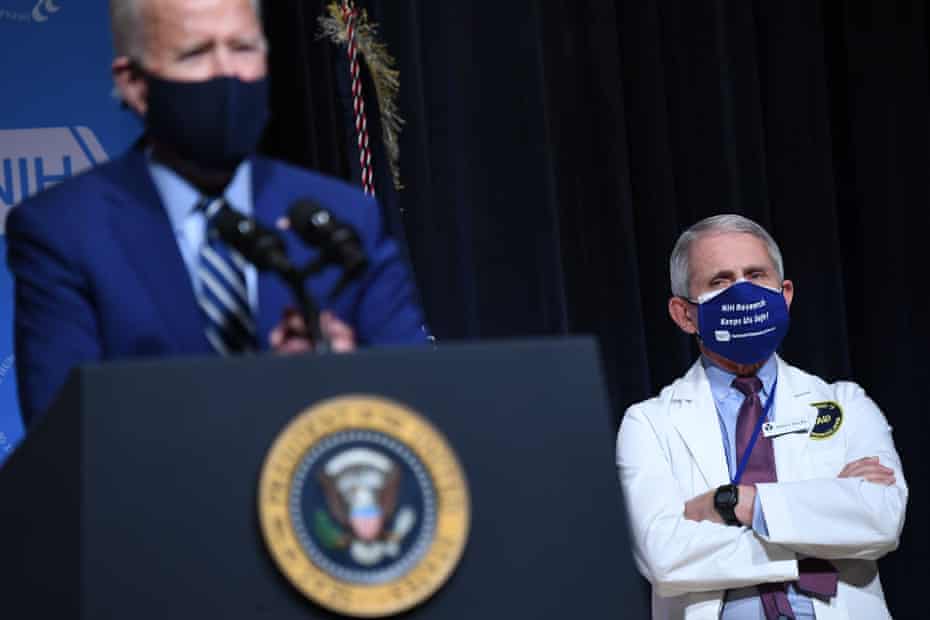

Nearly seven years later, the HIV expert and director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has become a household name throughout the world as the adviser to the White House on the Covid-19 pandemic, appearing in the media daily and speaking plainly about the science and the nature of the virus.

Prof Sharon Lewin, the inaugural director of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Australia, was co-chair of that 2014 event, the largest health conference yet held in Australia. Like Fauci an internationally renowned infectious diseases expert and scientist, Lewin has been critical in advancing understanding of the HIV latency – the time between being exposed to the virus and it causing disease – and she continues to lead clinical trials advancing potential cures.

Fauci and Lewin, who are friends and who have appeared on panels together at conferences throughout the world for decades, have become instrumental in the fight against Covid alongside other colleagues from the HIV field. Lewin co-chairs Australia’s National Covid Health and Research Advisory Committee, which advises the chief medical officer.

So why are HIV experts proving so critical in helping the world to understand and prevent Covid?

“My theory is HIV has been the biggest pandemic the world has ever seen,” Lewin says. “Because of its size, scale and gravity a whole generation of people have been trained in both high-income and low-income countries as virologists, immunologists and in pathogenicity – how viruses cause disease – and these areas are what people working on HIV have been working on for the last 40 years.

“All those skills are needed in response to Covid.”

There are similarities between Sars-CoV-2, which is the virus that causes Covid-19, and human immunodeficiency virus. It has meant diagnostic tests, antibody tests and even vaccine design have been able to leverage advances made in HIV.

“There’s lots of parallels between these two viruses, even though Covid is spread by a respiratory route and HIV is a blood-borne virus,” Lewin says. “But both viruses have this complex interplay with the immune system. HIV, just like Covid and also influenza and other viruses, get inside cells through a surface protein that is called different things in different viruses. It can be called an ‘envelope protein’, or in coronavirus it’s called a ‘spike protein’.”

It means the viruses enter human cells in a similar way, by binding to the surface of the host cell then fusing with it.

But the epidemiology, transmission and the way disease develops are vastly different.

“A key difference is that in Covid the antibodies produced by the body work, meaning that they bind to and neutralise the virus, and in most cases a person clears it from their body,” Lewin says. “Or, you can vaccinate someone and get these really good antibodies and prevent becoming infected.

“With HIV you also make lots of antibodies – and they’ve been studied to death over the last 30 years – but the antibodies that you make in HIV just aren’t very good. They’re non-neutralising, meaning they bind to the virus but they don’t wipe it out. Antibodies just aren’t enough to protect against HIV.”

The other key difference is that HIV gets inside and integrates with DNA. “It means it stays with you forever,” she says.

Lessons have also been learned from HIV about how to respond to a pandemic and how to engage the public to take on health and hygiene measures, Lewin says – and what not to do. She recalls that HIV was initially ignored as it emerged around the world.

“The famous story is that US president Ronald Reagan never said the word HIV in his entire presidency and HIV emerged under his leadership,” Lewin says. “So HIV has had the opposite problem to Covid, which has seen an initial massive global response.

“HIV may seem very visible to many people now, but in fact it was ignored for a very long time and was quite difficult to raise awareness and a desire to do something about it.”

While there is now much investment and collaboration when it comes to HIV, and public health responses that reduce stigmatisation and encourage testing have been adopted in the approach to tackling other diseases worldwide, Lewin says Covid has revealed what can be achieved when there are almost unlimited resources from the private and academic sector, with everyone focused on the problem from the outset.

“You can really do remarkable things,” she says.

Could we also have a vaccine for HIV had the world responded to that pandemic in the way that it did to Covid?

“I think many people living with HIV are asking that,” Lewin says.

“But there is no doubt HIV is a much harder vaccine to make, because there’s no natural experiment of vaccination, meaning that no one clears HIV. So when you make a vaccine you’re basically trying to mimic the immune response that clears a virus. With HIV, no matter how good your immune response is, the virus doesn’t go away so we don’t have any natural immunity to mimic.”

Lewin says while her HIV work has largely been able to continue even as she and her colleagues turn their attention to Covid, in the US and other countries grappling with high levels of Covid in the community, the entire focus is on Covid. This is a concern, she says, with HIV still an important and major pandemic that about 37 million people worldwide are living with. It’s essential that this work be continued, she says.

But just as tackling HIV has helped the world grapple with Covid, Lewin is hopeful that scientific advances made in the search for Covid vaccines and treatments will be able to benefit HIV research once the experts can return their full focus to that disease.

“I’m convinced of that,” Lewin says. “People had been working on mRNA vaccines for a long time with HIV, and they never got to phase 2 clinical trials. Those will move at great speed now.”

The Pfizer/BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine is the world’s first mRNA vaccine produced for human use, and is clever because it gives human cells instructions for how to make a protein unique to Covid. The protein is harmless but the body recognises it should not be there and begins to build an immune response. If infected with the real virus, the body will know how to attack.

“Those HIV mRNA studies will move at great speed now,” Lewin said. “Antibodies now being used for Covid treatment were first developed for HIV, but we have learned so much through Covid about manufacturing and ways of delivering antibodies. And finally, the infrastructure in place to diagnose and test for Covid can also be used for HIV.

“Once the Covid pandemic is over, all of this science will definitely have a big impact on the progress of HIV.”

This content first appear on the guardian