As COVID-19 vaccine distribution continues, the impact of the coronavirus on people moving into and out of the criminal justice system and the staff who work with justice-involved individuals is a key issue. This issue brief explores the impact of COVID-19 on justice-involved populations, examines how states have prioritized these populations for vaccination, and highlights the significance of Medicaid coverage for this population as well as proposals to expand access to Medicaid coverage. Looking ahead, key issues to watch include continued data on COVID-19 cases, deaths, and vaccinations among incarcerated populations as well as ongoing state and federal efforts to expand Medicaid access for this population. These efforts include the bipartisan Medicaid Reentry Act to allow Medicaid coverage for inmates 30 days prior to release, introduced in the Senate and also included in the House of Representatives COVID-19 relief budget reconciliation bill. This bill also includes funding for COVID-19 testing, contact tracing, and mitigation activities in congregate settings, including correctional facilities.

What does the data show about COVID-19 cases and deaths in prisons?

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published evidence that broad testing strategies in correctional facilities can help control transmission and provides considerations for such strategies, coronavirus testing policies vary across prison systems. Further, reporting of coronavirus cases and deaths data varies across states and prison systems and is often incomplete. In a February 9, 2021 letter to Congressional leadership, a group of Democrats indicated plans to reintroduce the COVID-19 in Corrections Data Transparency Act, a bill that would require correctional facilities to collect and publicly report detailed data on COVID-19 (including tests, cases, and deaths) and to disaggregate this data by demographics including sex, race, and disability. The group also urged leadership to include additional provisions related to correctional facilities in the upcoming COVID-19 relief package, including a requirement for routine diagnostic testing in correctional facilities.

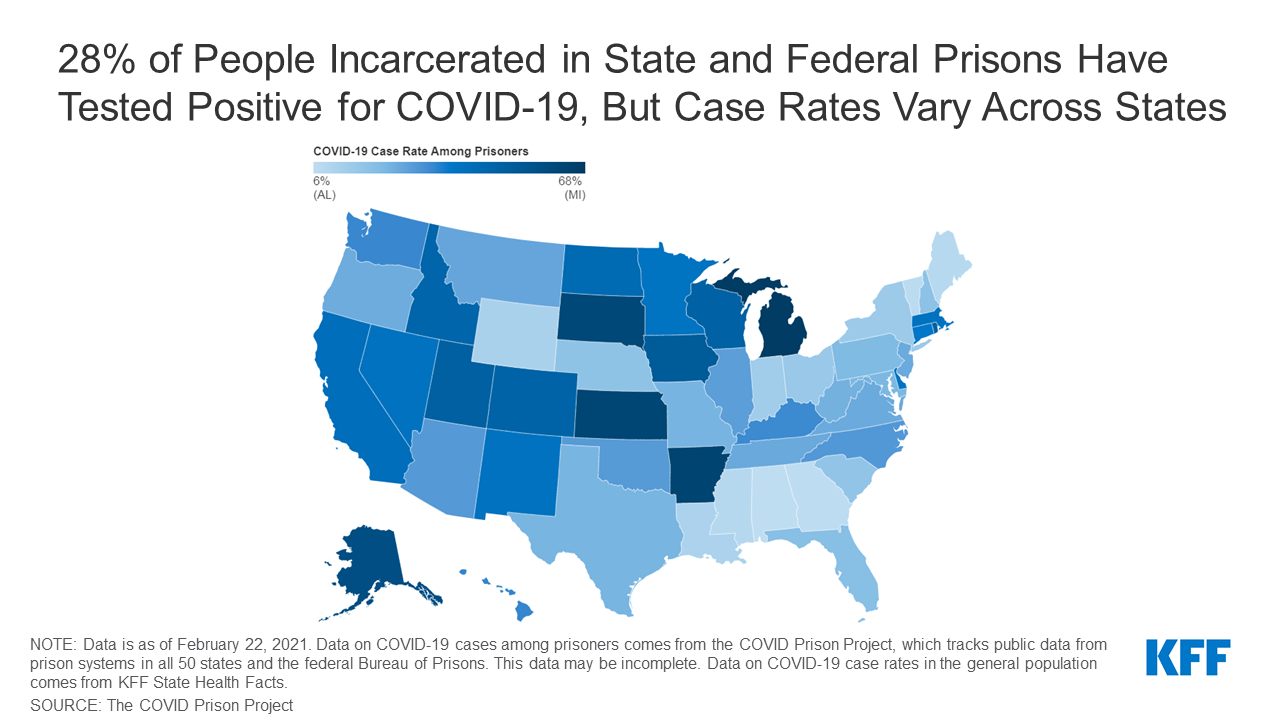

Coronavirus infection rates among incarcerated populations have been higher than overall infection rates in nearly all states (Figure 1). Data shows 388,168 reported cases of coronavirus among people incarcerated in state and federal prisons as of February 22, 2021, meaning that about 28% of this population has tested positive for the virus as compared to about 9% of the total US population. These case rates vary across states, ranging from 6% of prisoners in Alabama to 68% in Michigan. This variation in case rates may reflect variation in the number of prisoners being tested in addition to the prevalence of the virus. In all but three states, the coronavirus case rate among prisoners is higher than the case rate for the total population. The total coronavirus case rate among prisoners also reflects high case rates among the population detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) (69%) and among the population detained by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (29%). Additionally, since the start of the pandemic, an estimated 93,190 prison staff members have tested positive for coronavirus (22% of this population); however, data for staff is more limited as not all states report staff infections and even where this data is reported, prisons are less likely to systematically test staff and thus these counts may only include staff members who voluntarily report a positive diagnosis.

More than 2,300 deaths from coronavirus have been reported among prisoners, with death rates among prisoners higher than overall death rates in most states (Figure 2). A few states have not reported coronavirus deaths among prisoners, and the data that is available is subject to variation and limitations noted previously. This coronavirus death total includes deaths among the population detained by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (236 deaths) and by ICE (9 deaths). Coronavirus death rates vary across states, ranging from 4.1 deaths per 10,000 prisoners in Wyoming to 43.7 per 10,000 prisoners in Nevada. These rates among prisoners are higher than overall coronavirus death rates in 26 states, lower than overall rates in 15 states, and about the same (within one percentage point) in 9 states. Given the high case rates among prisoners, it is unsurprising that death rates are also high; however, coronavirus deaths in prisons are likely partially mitigated by the fact that on average, just over 10% of prisoners are over age 55 (as compared to just over 30% of the general population) and it is well-documented that older adults are at higher risk of dying if diagnosed with COVID-19. Since the start of the pandemic, 152 deaths from coronavirus have been reported among prison staff.

How are inmates in correctional facilities reflected in state vaccine prioritization plans?

Although not all states have fully defined the populations prioritized for receiving the COVID-19 vaccine in their state vaccination plans, of those that have, just over half include inmates in their Phase 1a, 1b or 1c groups and almost all include corrections officers. Vaccine recommendations from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) classify corrections officers as frontline essential workers who should be eligible for the vaccine following Phase 1a. While ACIP does not explicitly recommend inmates as an early priority group, it does note that states may choose to vaccinate those residing in congregate living facilities, such as correctional/detention facilities, at the same time as frontline staff). Accordingly, state vaccine plans vary in their prioritization of inmates in correctional facilities, and states also vary widely in the number of incarcerated individuals who have been vaccinated thus far. As of February 22, 2021, inmates in correctional facilities are eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine in just 15 states. An additional three states are allowing vaccination for inmates only in some counties and an additional 15 states are allowing vaccination of staff but not inmates. Some (including members of Congress and current inmates) have argued that incarcerated individuals should be higher priority for the vaccine, while others have critiqued state policymakers for prioritizing incarcerated individuals ahead of others in their states.

Why is vaccine access particularly important for inmates?

Justice-involved populations may have a greater need for vaccines due to underlying health conditions and increased risk of transmission in correctional facilities. Coronavirus and other infectious diseases spread easily among people in jails and prisons given close quarters and shared spaces within correctional facilities, as is demonstrated by high coronavirus infection rates (Figure 1). Policies related to COVID-19 in prisons such as quarantining, isolation, and masking vary across states. In recognition of the increased risk of transmission in these types of facilities, the House of Representatives COVID-19 relief budget reconciliation bill includes funding for COVID-19 testing, contact tracing, and mitigation activities in congregate settings, including correctional facilities. Although on average younger than the general population, many incarcerated people are at risk for experiencing complications from coronavirus due to higher rates of chronic disease among this population as compared to the general population. Further, people of color are disproportionately likely to be incarcerated in jails and prisons, and data shows racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes in part due to higher rates of underlying health conditions. Despite increased risks for the justice-involved population, reporting from some states suggests that inmates are reluctant to take the COVID-19 vaccine, citing concerns about side effects as well as distrust of the prison health care system.

What current and future options do justice-involved individuals have for accessing health care?

Correctional facilities are required to provide health services to incarcerated individuals, and Medicaid can help cover the costs of inpatient hospital care for this population. The provision of health care to incarcerated individuals varies significantly across states and types of correctional facilities, and may include on-site infirmaries and/or contracts with outside health care providers. In fiscal year 2015, state departments of correction on average spent $5,720 per inmate to provide health care services. Current rules allow individuals to be enrolled in Medicaid while incarcerated, but the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy limits Medicaid reimbursement for incarcerated individuals to inpatient care provided at facilities that meet certain requirements, including hospitals. States can facilitate access to Medicaid coverage for incarcerated individuals by suspending rather than terminating Medicaid coverage for enrollees who become incarcerated, which over 40 states reported doing as of January 2019. Suspending eligibility expedites access to federal Medicaid funds if an individual receives inpatient care while incarcerated. Although data on prisoner hospitalizations due to coronavirus is largely unavailable, Medicaid would be an important payer for any such hospitalizations.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) and its expansion of Medicaid provided new coverage options for individuals upon release from correctional facilities. Although incarcerated individuals are not eligible to buy private health insurance through the Health Insurance Marketplace established by the ACA, they can access a Special Enrollment Period to sign up for private health coverage within 60 days of release even if there is not currently a Marketplace Open Enrollment Period. Further, particularly in states that have adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, many justice-involved individuals could be eligible for Medicaid coverage. Justice-involved individuals are disproportionately low-income, with a median income prior to incarceration 41% lower than the median income of non-incarcerated counterparts. Though incarcerated people in all gender, race, and ethnicity groups have substantially lower incomes as compared to their non-incarcerated counterparts, median incomes prior to incarceration are particularly low for women of color. In the 39 states that have adopted Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, nearly all adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($17,774 for an individual in 2021) are eligible for Medicaid; however, eligibility for adults remains very limited in the remaining 12 states. In states which suspend Medicaid coverage for incarcerated individuals, individuals can have their coverage active immediately upon release, which facilitates access to health care services in the community. This policy is of particular importance during the coronavirus pandemic, as some prisons have implemented early or temporary release policies to reduce prison density and viral transmission. Researchers have urged states to establish and/or strengthen systems to help enroll individuals in Medicaid upon release to protect their health and that of the general population during the pandemic.

Looking ahead, policy proposals at the state and federal level could further expand Medicaid access and increase continuity of care for justice-involved populations during and beyond the pandemic. A few states are attempting to expand the scope of services provided to incarcerated individuals that can qualify for reimbursement through Section 1115 waiver requests. For example, Utah and Kentucky have pending requests that would provide limited benefits to certain inmates with substance use disorders prior to release. At the federal level, the Medicaid Reentry Act is a legislative proposal which would allow states to cover services for Medicaid beneficiaries who are incarcerated during the 30 days preceding their release, which could facilitate coverage and access to care post-release. This proposal is included in the House of Representatives COVID-19 relief budget reconciliation bill (to be funded for five years) and a bipartisan group of Senators has introduced similar legislation. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that the proposal in the reconciliation bill would increase federal costs by $3.7 billion over the five-year period and result in about 55% of all inmates being enrolled in Medicaid at the end of this period.